Spectra Assure Free Trial

Get your 14-day free trial of Spectra Assure

Get Free TrialMore about Spectra Assure Free Trial

Over the past few years, malware threats have increasingly started targeting the industrial control systems. These threats are becoming so concerning that the FBI recently had to issue a public warning about one in particular. As ZDNET reported, the US private sector was warned about a malware campaign that targets supply chain software providers. The malware referenced by this report was Kwampirs RAT - the malicious tool of choice from the Orangeworm group.

Given the possible ramifications this campaign might have, we've decided to leverage the Titanium platform for research into its inner workings. From the threat analysis viewpoint, the most important part of this malware is its configuration (control servers, mutex it uses, registry keys it creates…), since it's essentially a remote access trojan (RAT).

Following the breadcrumbs left in the network configuration, malware evolution can be mapped to the campaigns carried out by the group. By investigating the connections of this malware to the reports of new malware, its activity can be independently corroborated. But more importantly, documenting the malware network infrastructure can help the defenders protect their organizations from the ongoing attack more efficiently.

Every research builds upon what’s already been disclosed, and so we started ours by finding previous publications. As the referenced ZDNET article reports, this group has used the malware since 2015, so it is safe to assume that a technical analysis of the threat already exists. Two such technical reports were referenced in the article: the first one from Symantec, and the second from Lab52. Symantec's report was older and provided some technical details, but it mostly focused on IOCs. On the other hand, Lab52’s report provided a more in-depth technical analysis of the malware, listed used modules, and described the dropping and infection phases in detail. This report also included a link to a tweet containing YARA rules that can be used for detecting Kwampirs.

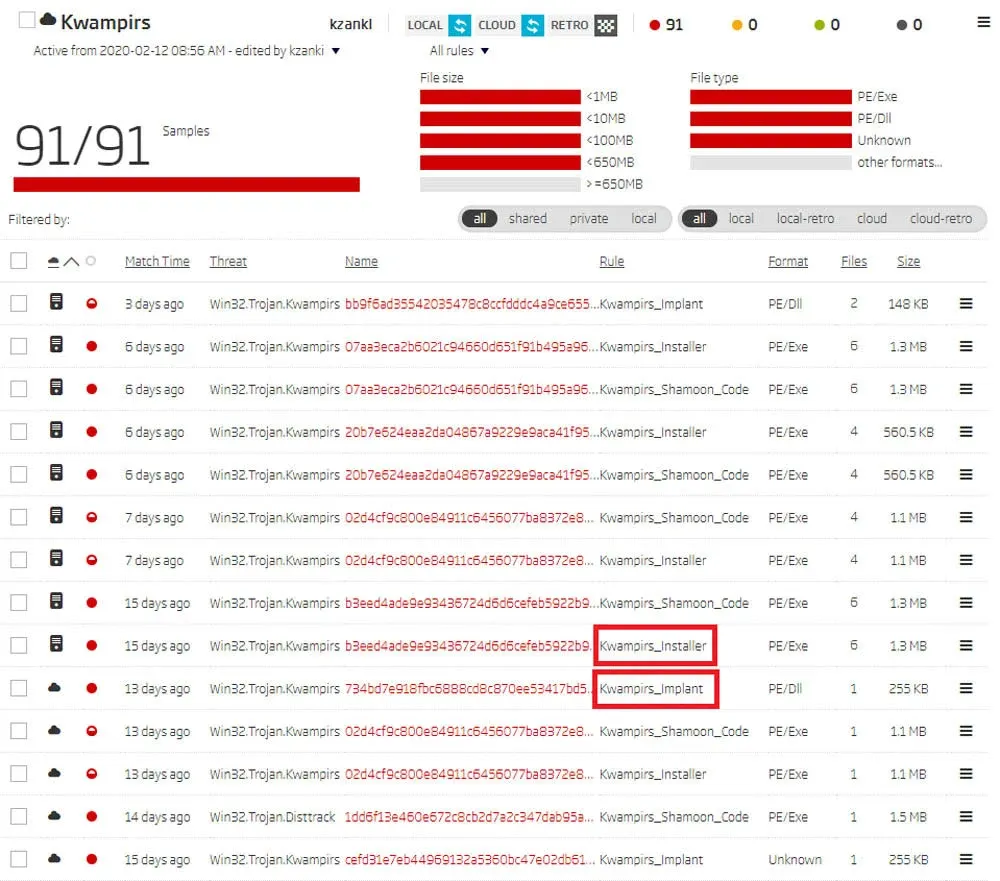

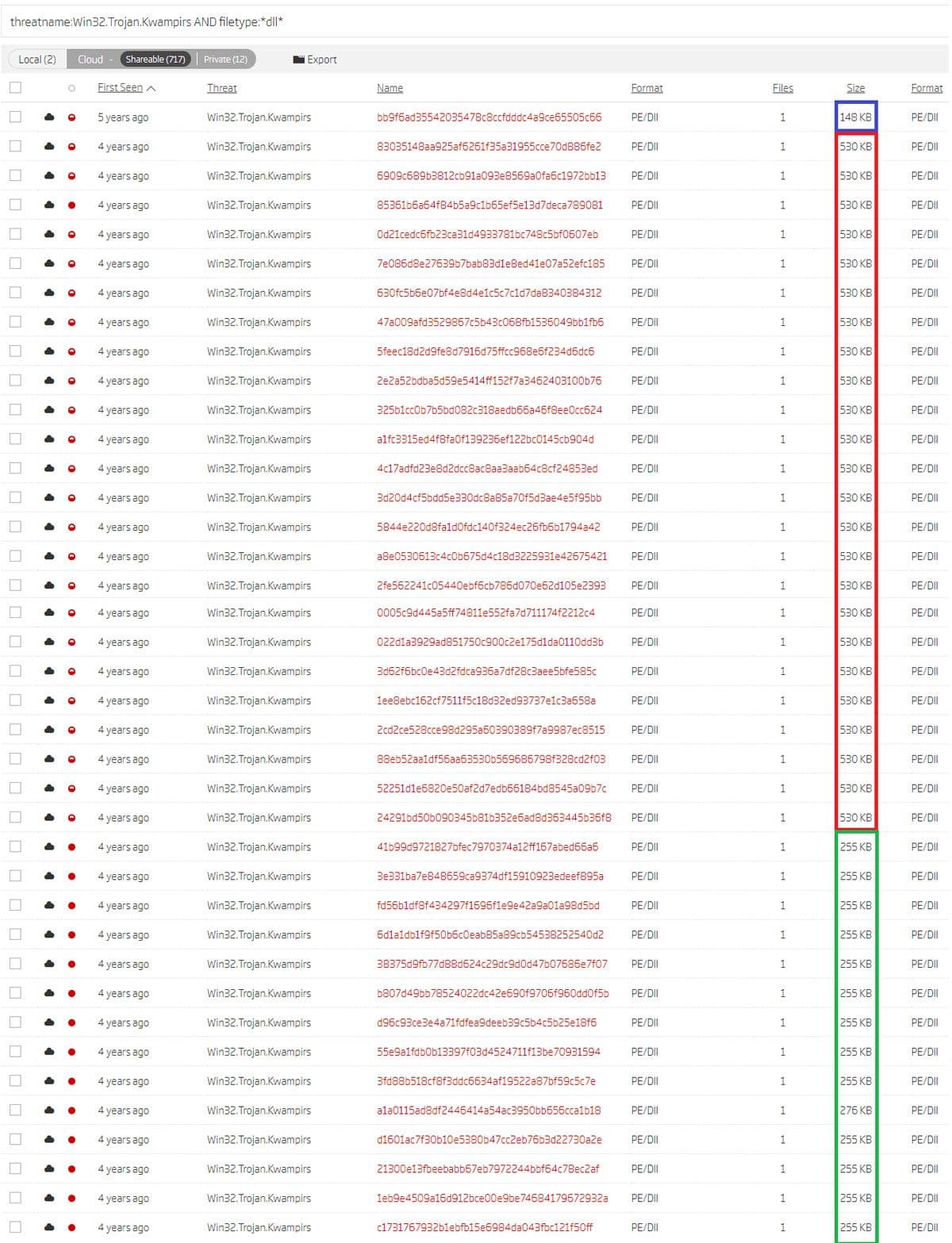

The next logical step in our research was to acquire the samples. Publicly available YARA rules are a perfect starting point, as they are easily deployed to the ReversingLabs A1000 threat analysis platform. The Retro Hunt feature offers a quick way to match those YARA rules against all samples seen by the Titanium Platform in the last 90 days. By Retro Hunting with those rules, we found the following samples.

Retro Hunt results on ReversingLabs A1000

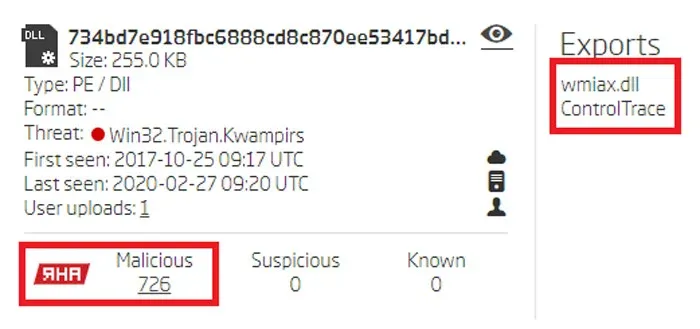

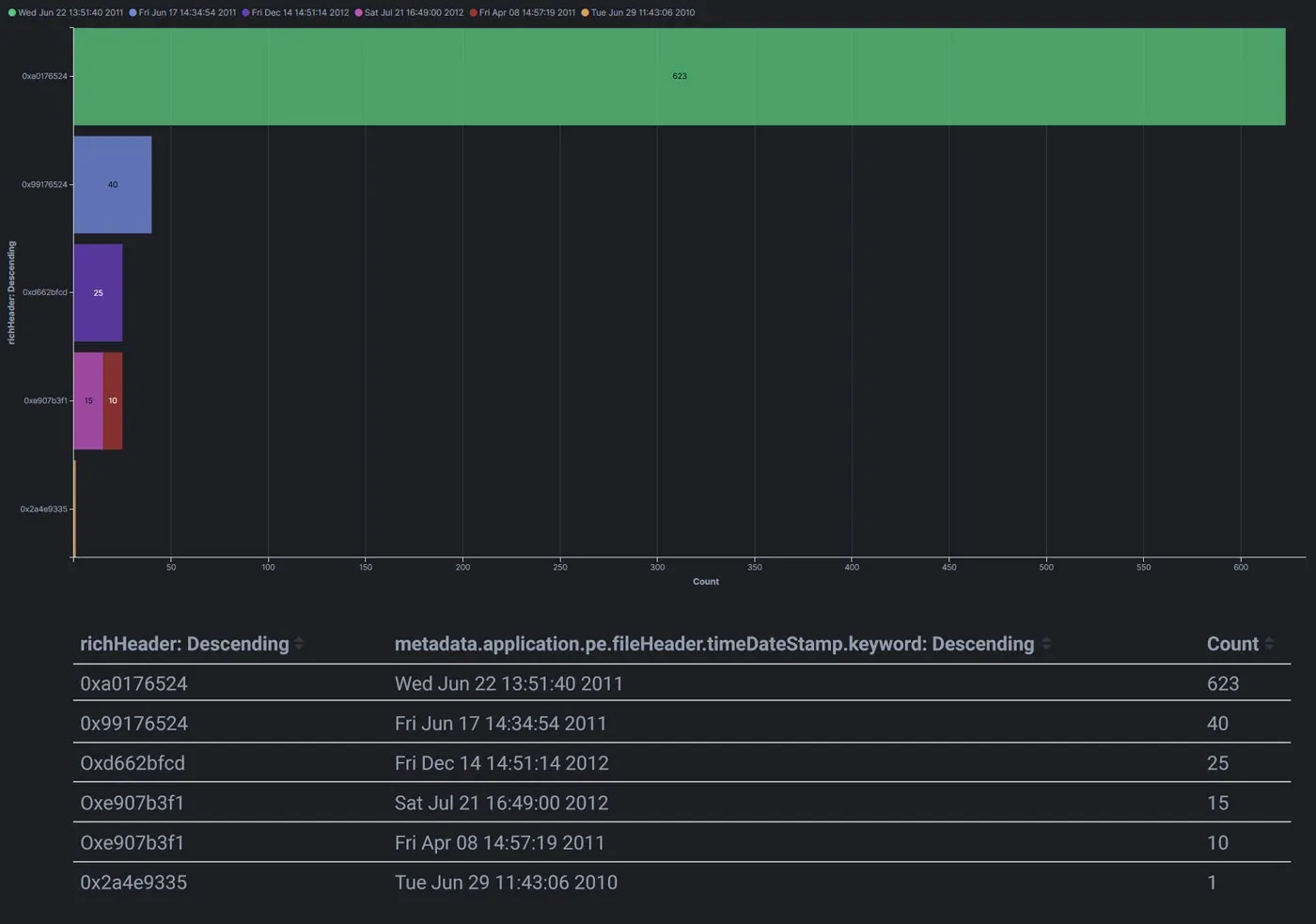

As the previously mentioned Lab52 technical analysis describes, the main RAT functionality can be found in the DLL payload of the installer.

Functions Exported by the RAT DLL

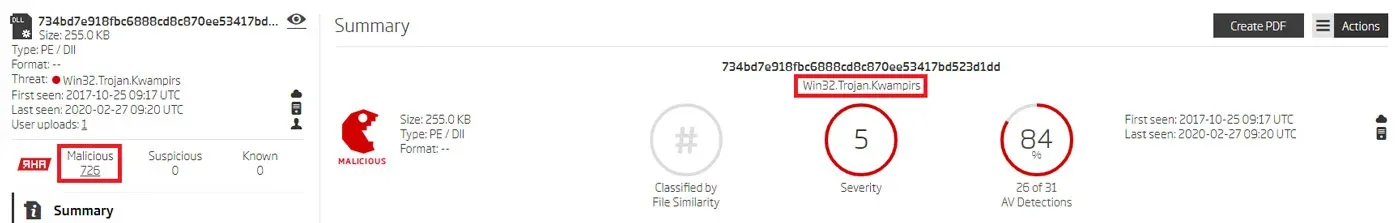

The Titanium platform analysis matched the facts described in the referenced technical analysis. The DLL exports only one function named ControlTrace. Furthermore, the similarity analysis also showed that this sample shares the same functionality with 726 other samples within ReversingLabs TitaniumCloud, grouped by the RHA1 similarity algorithm. These findings significantly expanded the analysis sample set.

Threat name associated with the RAT sample

Looking to complete the set, we picked another pivoting point - the detected threat name; in this case, Win32.Trojan.Kwampirs. Searching for all samples of the DLL file type with this threat name yielded even more matches.

The results of this search query, when sorted by their First Seen property, revealed even more interesting data points. Sorting by First Seen time naturally groups these samples based on their file size. This pivoting helps not only with grouping, but also with discovering additional Kwampirs RAT versions.

Search results sorted by their first occurrence and based on threat name and file type

Investigating the code patterns revealed strong similarities between the 530 KB samples and the 255 KB samples described in the existing technical report. The main difference between them was the BMP image found in the resources, which is actually an encrypted PE32 executable. This was only found in the dropper of the 255 KB samples. The second significant difference was that C2 hosts were stored as plaintext.

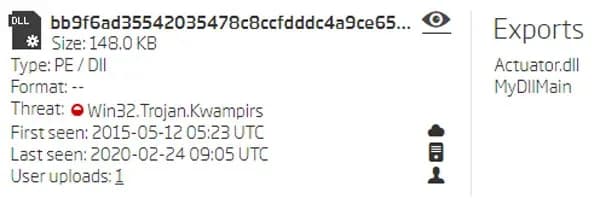

The code patterns of the 148 KB sample slightly differed from the others. However, the configuration decryption key and algorithm were still the same. Also, the exported function name was not ControlTrace - it was MyDllMain, and the original DLL name during compilation wasn’t wmiax.dll but Actuator.dll instead.

Functions exported by the newly discovered sample

Pivoting around the original DLL name uncovered another interesting sample that was not attributed to Win32.Trojan.Kwampirs like the others.

Pivoting on new Export names

Analyzing this sample and comparing it to the previous one showed that they were practically the same. This final sample had slightly simpler logic in some places, but the extracted domains were identical. The most interesting difference between the two was the User Agent string. The majority of Kwampirs samples have the User Agent string set to something like “Mozilla/…”, but this sample had it set to “ItIsMe”. These facts, combined with the first occurrence dates in our cloud, led to the conclusion that this was an earlier version in the RAT’s development process.

User Agent strings difference

Collecting the samples is more than a data hoarding exercise. It's necessary for writing a reliable malware configuration parser that extracts network configurations from collected samples - primarily the C2 URLs. These URLs are interesting because of the way this RAT finds active C2 servers. Every sample comes with a hardcoded list of 200 URLs that it tries to access in the sequential order. The C2 locations are either in the form of domain names or IP addresses. The malware uses the first active URL it finds as the C2 server.

Since the malware configuration is hidden away in the installer that drops the DLL onto the system, an unpacker needs to be created alongside the parser. This unpacker decomposes the installation component and extracts the DLL, allowing the parser to collect the necessary C2 information.

Using this combination of extraction and parsing, roughly 1600 URLs were collected. There was some duplication in the list, as some URLs were found within multiple samples. When this data was deduplicated, the number of URLs decreased to 1586 URLs.

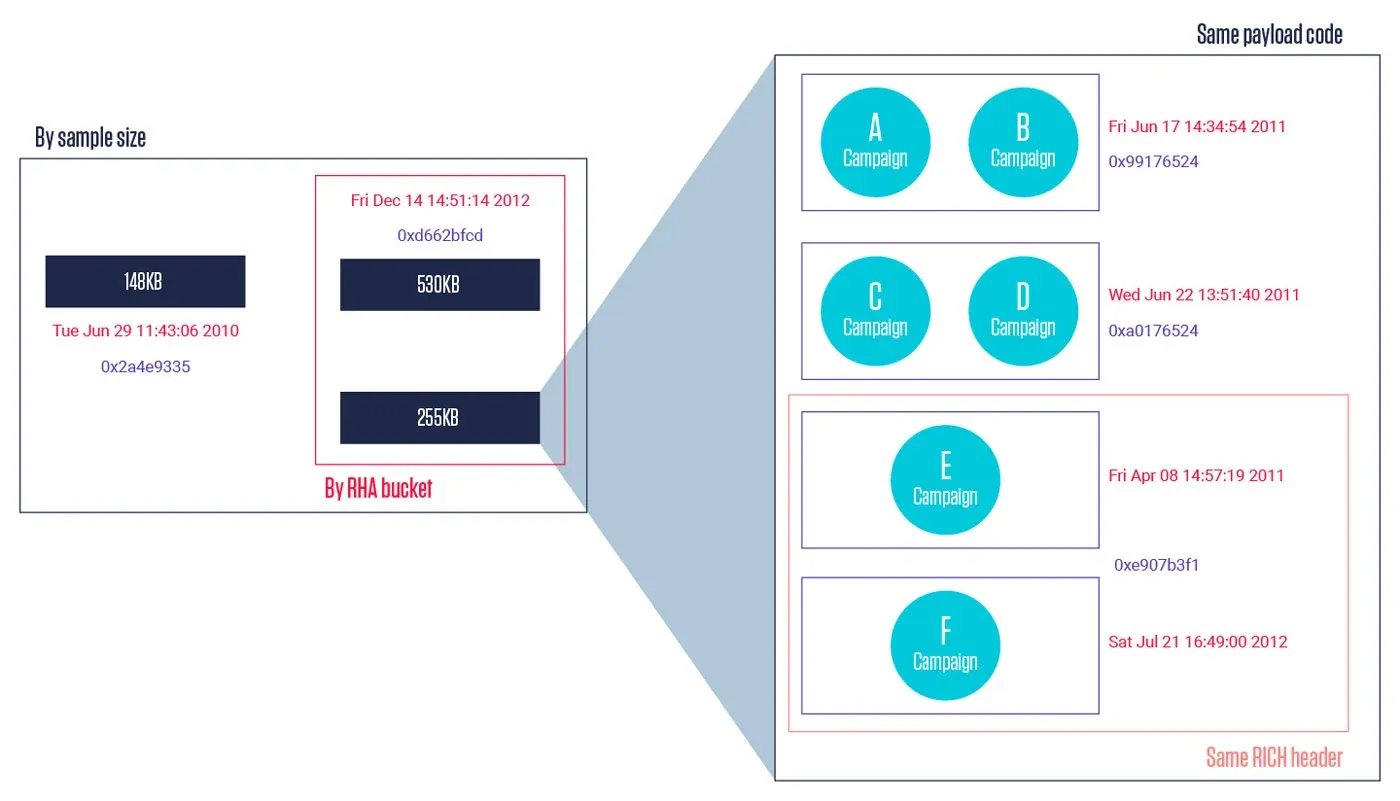

Analyzing the results of the extraction revealed that some of the droppers used the same payload, even though their hashes were different. The only difference between those samples was a 64-byte string used for random file name generation as a part of its execution logic. This indicates that the new dropper samples recently seen in the cloud are, in fact, freshly compiled, even though they use the old DLL payloads.

Malicious operations are usually carried out in waves (or campaigns) that typically share the same control server infrastructure. Each of the Kwampirs samples we collected came with a set of 200 control server URLs. Since 1586 of those URLs were unique, it is safe to assume they were remnants of multiple campaigns. As the number of extracted URLs is not a multiple of 200, it is likely that some parts of the network infrastructure were reused by multiple campaigns.

Grouping samples into campaigns is a challenge. One way to split the dataset is by the time of discovery, but it might not be the best way. In this case, some samples were already nicely grouped together by the combination of their size and their discovery time. However, that still left a large set of 600+ samples of files 255 KB in size.

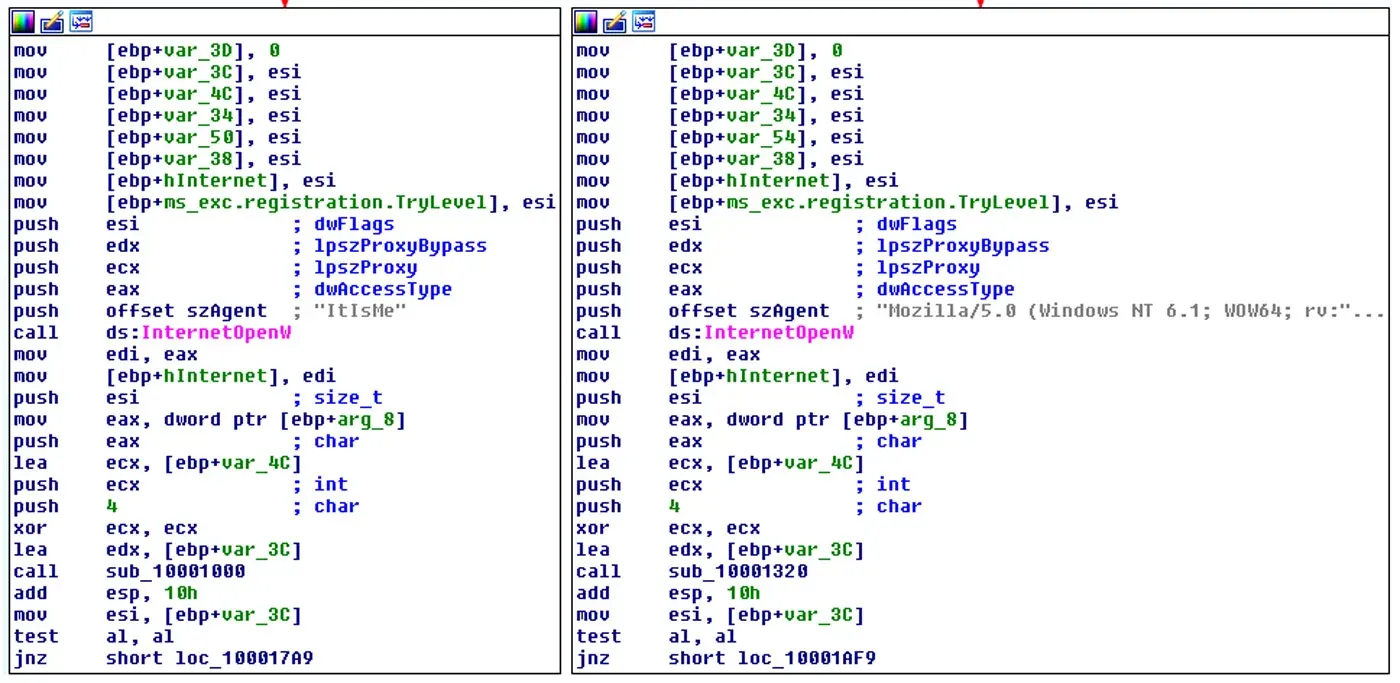

Since this collection of samples was too big for manual inspection, we relied on static analysis for assistance. Processing the samples with our Titanium platform and plugging the results into the ELK stack could help us find suitable grouping criteria.

Right away, two of the metadata fields struck us as the most convenient - Rich header information and the file compilation timestamp. Rich header is a structure that often appears in PE files just before the PE signature. It contains information about the compiling and linking processes, such as the toolchain version artifacts. In this case, Rich header revealed that all samples were compiled with Visual Studio 2010. Their timestamps did not correlate with their first appearance in our cloud, which was in May 2015 and later. In fact, they all appeared as if they had been compiled a few years before their appearance in the cloud. Given what’s known about the operations of this group, it probably means that the samples were compiled in a virtual machine with deliberately inaccurate time.

Rich header and timestamp grouping

Grouping the samples based on these criteria produced much cleaner results for the domains extracted from them. Each group of samples had one or two sets of URLs in their configurations, which were repeated the same number of times. With that, the grouping was complete and it provided the following insight into the sample-to-campaign relationships.

Final grouping of samples

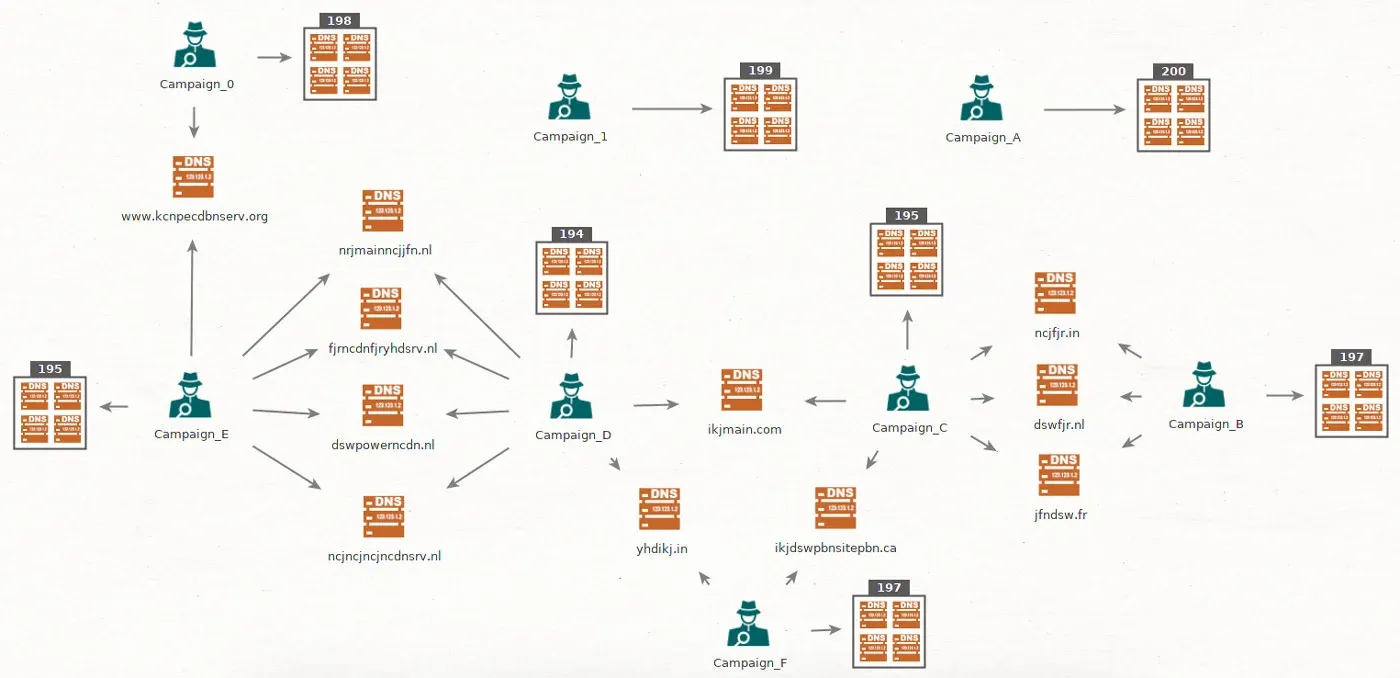

For visualization purposes, the extracted data was loaded into Maltego that created a graph showing correlation between samples and the domains used across different campaigns. This confirmed that most of the campaigns were interconnected by one or multiple control domains.

Campaign correlation and connectivity

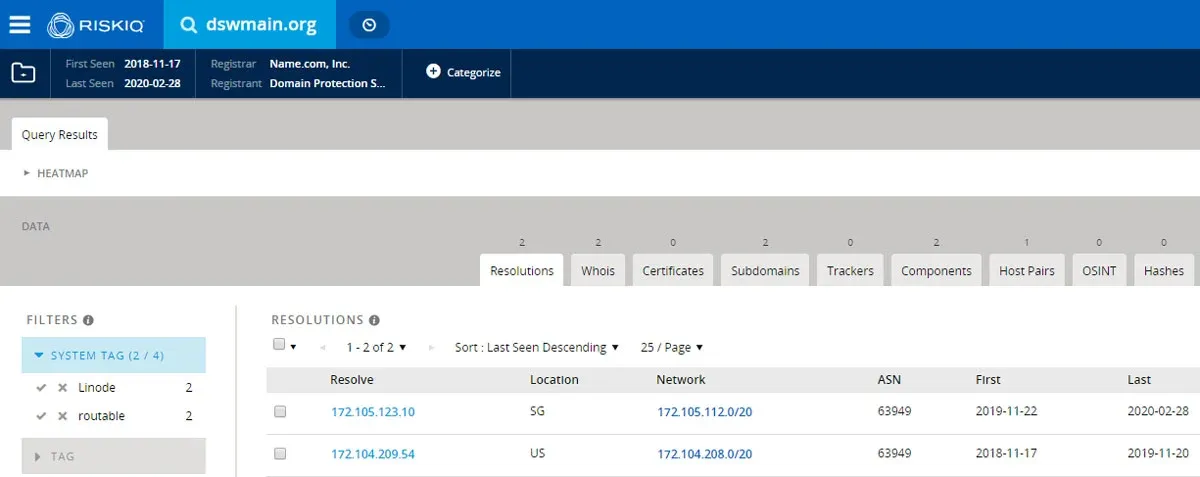

Processing historical DNS resolution data for one of the domains extracted from a recently seen sample revealed more interesting data. As shown in the RiskIQ’s Passivetotal, the domain dswmain.org that was seen in CampaignC resolved to two hosts in the past.

Historic DNS resolution for dswmian.org site

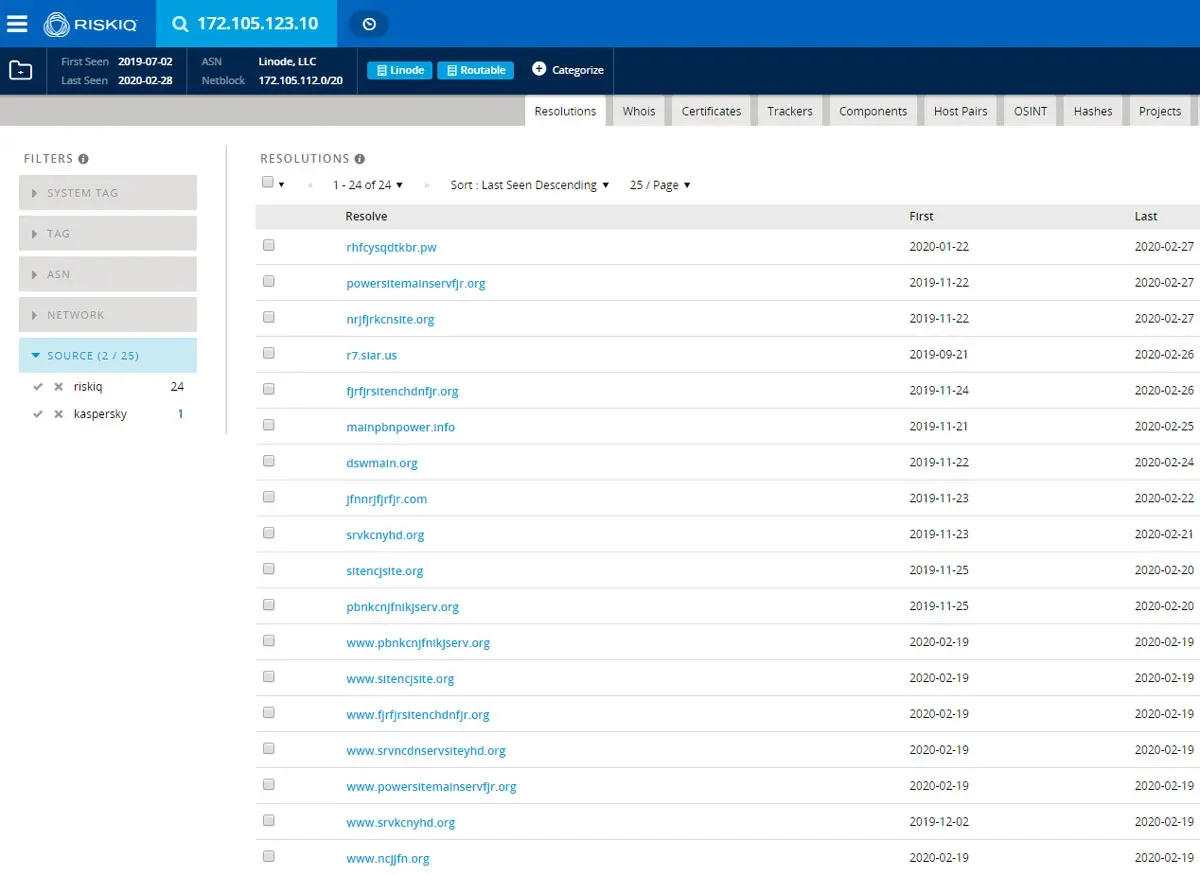

Currently it redirects to a sinkhole server with the IP address 172.105.123.10. Looking at the list of the domains that have resolved to that host, we can see more domains that are part of Kwampirs campaigns - not all of them, but a small subset. Most of the extracted domains don’t resolve to anything yet, so they could be used as backup domains when the active control domain is compromised or goes down. Since this was a sinkhole server, this information couldn’t confirm the assumption that these campaigns shared the infrastructure, but it does show which domains were used and when they were used in the past.

Pivoting on the resolved IP address

Interestingly, a few domains on that list haven’t been extracted from any of the encountered samples. However, they do look like the domains that Kwampirs could have used, since they consist of several repeated random letters. This might mean there are a few more campaigns for which the samples are yet to be collected. Still, based on the timeline when these domains were first seen by the passive DNS service, it is likely that they are used by some older samples, and are part of a campaign that’s already been mapped.

Protection from supply chain attacks is two-fold. Organizations must protect their development environment and ensure their suppliers are not compromised. Kwampirs RAT represents a targeted attack against the secure software supply chain, and needs to be closely monitored for new activity.

Warnings issued by the FBI are corroborated by our research presented here. The attackers are still using the same methods of infection, tools, and network infrastructure, which indicates that their activity is constant.

Converting open source threat intelligence into actionable data is a difficult task made easy with the ReversingLabs Titanium Platform. Pulling from a vast data repository, it enables the defenders to collect necessary samples and extract valuable IOCs that can be used to protect the organisation from past and ongoing attacks.

The following links contain the data extracted from the collected samples. These IOCs can be used to improve the security of your organizations by creating blocking firewall and intrusion detection systems rules. They can also be used to search the SIEM logs for infected endpoints. IOCs are grouped as described previously in this article.

SHA1: https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/IOC%20list/SHA1_LIST.txt

Campaign 0: https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/IOC%20list/Campaign_0_IOC.txt

Campaign 1: https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/IOC%20list/Campaign_1_IOC.txt

Campaign A: https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/IOC%20list/Campaign_A_IOC.txt

Campaign B: https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/IOC%20list/Campaign_B_IOC.txt

Campaign C: https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/IOC%20list/Campaign_C_IOC.txt

Campaign D: https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/IOC%20list/Campaign_D_IOC.txt

Campaign E: https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/IOC%20list/Campaign_E_IOC.txt

Campaign F: https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/IOC%20list/Campaign_F_IOC.txt

Read our other RAT blogs:

Explore RL's Spectra suite: Spectra Assure for software supply chain security, Spectra Detect for scalable file analysis, Spectra Analyze for malware analysis and threat hunting, and Spectra Intelligence for reputation data and intelligence.

Get your 14-day free trial of Spectra Assure

Get Free TrialMore about Spectra Assure Free Trial