Spectra Assure Free Trial

Get your 14-day free trial of Spectra Assure

Get Free TrialMore about Spectra Assure Free Trial

ReversingLabs:

SolarWinds, a company that makes IT monitoring and management solutions, has become the latest target of a sophisticated supply chain attack. Multiple SolarWinds Orion software updates, released between March and June 2020, have been found to contain backdoor code that enables the attackers to conduct surveillance and execute arbitrary commands on affected systems.

ReversingLabs' research into the anatomy of this supply chain attack unveiled conclusive details showing that Orion software build and code signing infrastructure was compromised. The source code of the affected library was directly modified to include malicious backdoor code, which was compiled, signed and delivered through the existing software patch release management system.

While this type of attack on the software supply chain is by no means novel, what is different this time is the level of stealth the attackers used to remain undetected for as long as possible. The attackers blended in with the affected code base, mimicking the software developers’ coding style and naming standards. This was consistently demonstrated through a significant number of functions they added to turn Orion software into a backdoor for any organization that uses it.

Piecing together a story from the outside of the incident is difficult. However, the trail of breadcrumbs left behind is sufficient to glean some insight into the methods the attackers used to compromise the Orion software release process.

Such an investigation typically starts with what’s known, which in this case is the list of backdoored software libraries. A file named SolarWinds.Orion.Core.BusinessLayer.dll within the Orion platform software package update SolarWinds-Core-v2019.4.5220-Hotfix5.msp is the first version known to contain the malicious backdoor code. That library has been thoroughly analyzed in FireEye's technical blog, which describes the backdoor behavior very well.

However, we can draw further conclusions about the attackers’ patience, sophistication and the state of Orion software build system from the analysis of metadata.

While the first version to contain the malicious backdoor code was 2019.4.5200.9083, as outlined by the FireEye blog, there was a previous version that was tampered with by the attackers: version 2019.4.5200.8890, from October 2019, and this version had only been slightly modified. While it doesn’t contain the malicious backdoor code, it does contain the .NET class that will host it in the future.

![Empty .NET class prior to backdoor code addition [ver. 2019.4.5200.8890]](/_next/image?url=%2Fapi%2Fmedia%2Ffile%2Fsunburst-01-sw-prebackdoor.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Figure 1. - Empty .NET class prior to backdoor code addition [ver. 2019.4.5200.8890]

This first code modification was clearly just a proof of concept. Their three step action plan: Compromise the build system, inject their own code, and verify that their signed packages are going to appear on the client side as expected. Once these objectives were met, and the attackers proved to themselves that the supply chain could be compromised, they started planning the real attack payload.

The name of the class, OrionImprovementBusinessLayer, had been chosen deliberately. Not only to blend in with the rest of the code, but also to fool the software developers or anyone auditing the binaries. That class, and many of the methods it uses, can be found in other Orion software libraries, even thematically fitting with the code found within those libraries. This implies not only the intent to remain stealthy, but also that the attackers were highly familiar with the code base.

Compare, for instance, the functions that compute the UserID. In the Orion Client code, this function tries to read the previously computed value from the registry, or creates a new GUID for the user.

![GetOrCreateUserID in Orion Client [ver. 3.0.0.349]](/_next/image?url=%2Fapi%2Fmedia%2Ffile%2Fsunburst-02-sw-getorcreateuserid-legit.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Figure 2. - GetOrCreateUserID in Orion Client [ver. 3.0.0.349]

Mimicking that, the attackers created their own implementations of these functions to also compute the UserID, and named them the same way. Their functions are even using the same GUID format for the ID type later on.

![GetOrCreateUserID in backdoor class [ver. 2019.4.5200.9083]](/_next/image?url=%2Fapi%2Fmedia%2Ffile%2Fsunburst-03-sw-getorcreateuserid-backdoor.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Figure 3. - GetOrCreateUserID in backdoor class [ver. 2019.4.5200.9083]

While not spot on, this code performs a similar function as the original. The pattern of naming classes, members, and variables appropriately is visible everywhere in the backdoored code.

There really is a method called CollectSystemDescription and UploadSystemDescription used by Orion Client library code. Just like there was an IOrionImprovementBusinessLayer interface the attackers mimicked for the name of the class in which they placed the backdoor code.

However, any code added to the library doesn’t just magically execute itself. The attackers still need to call it somehow. And the way that was done tells us that the build system itself was compromised.

![RefreshInternal in the clean software version [ver. 2017.1.5300.1698]](/_next/image?url=%2Fapi%2Fmedia%2Ffile%2Fsunburst-04-sw-hijack-legit.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Figure 4. - RefreshInternal in the clean software version [ver. 2017.1.5300.1698]

![RefreshInternal in the backdoored library [ver. 2019.4.5200.9083]](/_next/image?url=%2Fapi%2Fmedia%2Ffile%2Fsunburst-05-sw-hijack-backdoor.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Figure 5. - RefreshInternal in the backdoored library [ver. 2019.4.5200.9083]

Code highlighted in red is the additional functionality the attackers put in. This small block of code creates a new thread that runs the backdoor while Orion software is performing its background inventory checks. Such a location is perfect for this kind of code to be added, as the original code is already dealing with the long-running background tasks. So like the rest of the attacker-injected code, it just blends in.

While there are techniques to decompile the .NET code, inject something new, and recompile the code afterwards, this wasn’t the case here. The InventoryManager class was modified at the source code level, and the file was ultimately built with the regular Orion software build system.

This can be confirmed by looking at the timestamps for the backdoored binary, other libraries within the same package, and the patch file that delivers them.

![Backdoored library compile time [ver. 2019.4.5200.9083]](/_next/image?url=%2Fapi%2Fmedia%2Ffile%2Fsunburst-06-sw-pe-fileheader.webp&w=1920&q=75)

Figure 6. - Backdoored library compile time [ver. 2019.4.5200.9083]

![Backdoored library PDB symbols time [ver. 2019.4.5200.9083]](/_next/image?url=%2Fapi%2Fmedia%2Ffile%2Fsunburst-07-sw-pe-codeviews.webp&w=1920&q=75)

Figure 7. - Backdoored library PDB symbols time [ver. 2019.4.5200.9083]

![Backdoored library signing time [ver. 2019.4.5200.9083]](/_next/image?url=%2Fapi%2Fmedia%2Ffile%2Fsunburst-08-sw-pe-certificate.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Figure 8. - Backdoored library signing time [ver. 2019.4.5200.9083]

Timestamps between the PE file headers and the CodeViews match perfectly. That, with the revision number set to one, means that the file was compiled only once – or that it was a clean build. Since the file was signed, and cross-signed for timestamping, the timestamps within the headers can be reliably validated. The cross-signing timestamp is controlled by a remote server that is outside of the build environment, and can’t be tampered with.

Signing occurred within a minute of library compilation. That leaves no time for the attackers to be able to monitor the build system, replace the binary and change the metadata to match this perfectly. The simplest way for all these timestamp artifacts to align perfectly is to have the attackers’ code injected directly into the source, and then have the existing build and signing system perform the compilation and release processes as defined by the Orion software developers.

![Backdoored library file modification time [ver. 2019.4.5200.9083]](/_next/image?url=%2Fapi%2Fmedia%2Ffile%2Fsunburst-09-sw-7zip.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Figure 9. - Backdoored library file modification time [ver. 2019.4.5200.9083]

Finally, the MSP patch file contains a CAB archive that preserves the local last modified time for the library. Which, assuming the build system is running in the GMT+1 time zone, also confirms that the file was last modified during signing.

The files surrounding the backdoored library that belong to the same namespace were also compiled at the same time. Since they don’t depend on each other, they wouldn’t be built at the same time unless the build system was not running a complete build.

Since the MSP patch file is signed, and its signing time matches the contents of the package, this confirms that the patch file was created on the same machine as the rest of the build.

The big question is: was source control compromised, or was the attackers' code just placed on the build machine?

Unfortunately, that is something the metadata can’t reveal. There are no such artifacts that get preserved during software compilation. But the attackers went through a lot of trouble to ensure that their code looks like it belongs within the code base. That was certainly done to hide the code from the audit by the software developers.

What is certain is that the build infrastructure was compromised. In addition, the digital signing system was forced to sign untrusted code. While there’s no evidence at the moment that SolarWinds certificates were used to sign other malicious code, that possibility should not be excluded. And, as a precaution, all certificates and keys used on that build system should be revoked.

Consider for a second the type of customer that runs Orion software within their environment. For a software supply chain attack like this to work, the attackers need to keep under the radar and evade millions of dollars of security investment. They need to fool the highly specialized detection software, the people that run it to detect threats, and use it to proactively hunt for anomalies – for months. To pull that trick off, the attackers need to strike the right balance between staying hidden and achieving their objective.

![Backdoored library obfuscated strings [ver. 2019.4.5200.9083]](/_next/image?url=%2Fapi%2Fmedia%2Ffile%2Fsunburst-10-sw-zipobfuscation.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Figure 10. - Backdoored library obfuscated strings [ver. 2019.4.5200.9083]

Large security budgets come with quite a lot of perks. Being able to do internal threat hunting is certainly one of them. And there’s nothing more threat hunters like to look for than anomalies in their data. YARA rules are just one way of finding odd things just laying about.

The string “Select * From Win32_SystemDriver” is probably found in quite a few of them. That is why the attackers chose to hide all such noisy strings with a combination of compression and Base64 encoding. Such a two step approach was necessary because there are also quite a few hunting rules out there that look for Base64 variants of aforementioned string.

By reversing those steps, C07NSU0uUdBScCvKz1UIz8wzNooPriwuSc11KcosSy0CAA== found above becomes “Select * From Win32_SystemDriver”. And all the threat hunting rules stay none the wiser.

Such string obfuscation is repeated throughout the code. And that’s the balance between standing out in a software developer review and fooling the security systems, a gamble that has paid off for the attackers.

Very few security companies are focused on securing the software supply chain. For most, talking about reducing the risks that these types of attacks pose is far-off. In many ways, we’re still in the problem awareness phase. And, as unfortunate as they are, incidents like this help draw attention to this multifaceted problem, one that equally affects those that ship software and those that consume it.

ReversingLabs research and development teams pride themselves with thinking about such big problems before they become widespread concerns. To that goal, we built many prototypes of products and solutions to address such problems.

Software supply chain protection is certainly a huge problem waiting to be solved. And internally, we've defined product strategies about protecting both sides of the equation - the developer and the user.

We envisioned a system able to scan “gold” software release images prior to their release or consumption. This system is purposely built to look for software tampering, digital signing, and build quality issues. It is ingrained into the continuous software development and release cycle, with the aim to bring these issues to the surface and provide guidance in eliminating them.

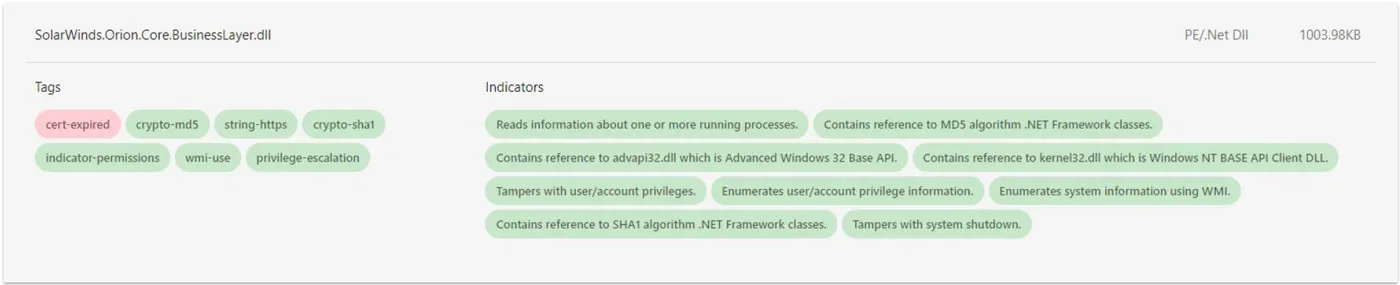

One key aspect of such a system is the ability to pinpoint behavioral differences between compiled software versions. Dubbed static behavioral indicators, these descriptions translate the underlying code actions into the effects they could have on the machine that runs them.

When layed out as a difference between added (green) and removed (red) code, the effects of software behavior changes become apparent. For the backdoored SolarWinds binary, this raises a number of security alarms that would have made it possible to catch this supply chain attack much sooner.

Figure 11. - Static behavior diff between ver. 2019.4.5200.8890 and ver. 2020.2.5300.12432

The following list highlights important static code behavior changes between the first tampered version and the one which contains the malicious backdoor code.

1. Reads information about one or more running processes

Having an application suddenly become aware of other running processes in the environment is highly unusual. For mature code bases, this functionality is typically added in major releases. There’s typically a big feature planned behind this kind of code. And there’s usually a good reason for the addition: some type of inter-process communication, or a desire to control running processes. In any other scenario, such an unplanned addition would be a cause for concern.

2. Contains references to MD5/SHA1 algorithm .NET Framework classes

While not highly unusual, hashing algorithms like MD5 and SHA1 are typically implemented to solve a specific problem. It’s either some sort of content validation, authentication, or uniqueness check. Each of these can usually be mapped to a high-level requirement and tracked back to a feature modification request or a similar development task.

3. Contains references to kernel32.dll / advapi32.dll native Windows API

Referencing native Windows APIs from .NET library all of a sudden is very unusual. While the underlying code that interacts with the system is a necessity, even for managed applications, there are better ways of doing it. For example, provided language runtimes can typically achieve the same effect as what most developers require from native functions, but without having to deal with type uncertainty. By itself, regardless of the supply chain attack context, this is what developers refer to as code smell.

4. Enumerates system information using WMI

Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) is a set of system functions that enable the application to get information on the status of local and remote computer systems. IT administrators use these functions to manage computer systems remotely. Understanding why such functionality is added suddenly is crucial. It is unlikely that the scope of the application has changed so dramatically that the interaction between remote computer systems has become a part of its key tasks. And if the goal is to retrieve something from the local system, there might already be code that has that information.

5. Enumerates and tampers with user/account privileges

Looking up user or account privileges is typically the first step in having them elevated. Running code at elevated privileges is done to perform a limited action, like copying files to restricted folders, manipulating running processes, changing system setting, etc. These are all actions that must have a firm reason behind them, and adding them to a mature code base is at least questionable. A developer should be made aware of this type of thing, and should have to sign off on it.

6. Tampers with system shutdown

Sticking with the theme of unnecessary privileges for an application, we have a big red flag at the end. Being able to shutdown or reboot a computer isn’t something that’s added to code unexpectedly. That is a feature that takes coordination between multiple code components, and is usually implemented at a single location within the application. Having it appear elsewhere is definitely cause for concern.

Regardless of the side of the software deployment process one finds themselves on, a report about the impact of software code changes is an invaluable piece of information. For software developers, it can lead to informed decisions about the underlying code behavior. And for software consumers, it can ensure detection of anomalous code additions. Either way, the impact of such a system is transformative to software deployment processes. It serves as a verification barrier that can make it harder for these kinds of software supply chain attacks to recur.

SUNBURST illustrates the next generation of compromises that thrive on access, sophistication and patience. For companies that operate valuable businesses or produce software critical to their customers, inspecting software and monitoring updates for signs of tampering, malicious or unwanted additions must be part of the risk management process. This type of tampering exploits software distributions that are trusted by the traditional security software stack, which is unique in comparison to known malicious implants. The distributions could not be easily inspected, if at all, by any perimeter control. Hiding in plain sight behind a globally known software brand or a trusted business-critical process, gives this method access that a phishing campaign could only dream to achieve.

Most cyber security frameworks such as NIST CSF document the need for continuous risk management and inspection of data and software. This, in turn, includes the need that all third party and open source software, whether built internally or externally, be continually inspected for tampering, malicious content, or any unwanted characteristics that clash with an organization’s acceptable policies.

ReversingLabs is always thinking about the big challenges that lay ahead. We’d be happy to discuss our viewpoints and offer solutions towards reducing organizational software supply chain risks. Please get in touch so that we can solve these problems together.

Referenced files:

File name | SolarWinds.Orion.Core.BusinessLayer.dll |

Version | 2019.4.5200.8890 |

TimeStamp | Thu Oct 10 13:26:39 2019 |

Hash | 5e643654179e8b4cfe1d3c1906a90a4c8d611cea |

Note | File contains placeholder OrionImprovementBusinessLayer class. |

File name | SolarWinds.Orion.Core.BusinessLayer.dll |

Version | 2019.4.5200.9083 |

TimeStamp | Tue Mar 24 08:52:34 2020 |

Hash | 76640508b1e7759e548771a5359eaed353bf1eec |

Note | First known instance of the backdoored library. |

File name | SolarWinds.Orion.Core.BusinessLayer.dll |

Version | 2020.2.5200.12394 |

TimeStamp | Tue Apr 21 14:53:33 2020 |

Hash | 2f1a5a7411d015d01aaee4535835400191645023 |

Note | Contains malicious backdoor code. |

File name | SolarWinds.Orion.Core.BusinessLayer.dll |

Version | 2020.2.5300.12432 |

TimeStamp | Mon May 11 21:32:40 2020 |

Hash | d130bd75645c2433f88ac03e73395fba172ef676 |

Note | Contains malicious backdoor code. |

File name | SolarWinds-Core-v2019.4.5220-Hotfix5.msp |

Version | 2019.4.5220 |

TimeStamp | Tue March 24 10:57:09 2020 |

Hash | 1b476f58ca366b54f34d714ffce3fd73cc30db1a |

Note | HotFix patch containing the first known backdoor instance. |

File name | SolarWinds.OrionImprovement.Client.dll |

Version | 3.0.0.349 |

TimeStamp | Wed May 22 11:56:49 2019 |

Hash | 22719783b2469ad312a40c1b200dd24d6a03618d |

Note | Attacker reference file containing IOrionImprovementBusinessLayer interface. |

Explore RL's Spectra suite: Spectra Assure for software supply chain security, Spectra Detect for scalable file analysis, Spectra Analyze for malware analysis and threat hunting, and Spectra Intelligence for reputation data and intelligence.

Get your 14-day free trial of Spectra Assure

Get Free TrialMore about Spectra Assure Free Trial