ReversingLabs is analyzing a supply chain compromise of the firm 3CX Ltd., a maker of enterprise voice over IP (VOIP) solutions. Beginning on March 22nd, 2023, compromised versions of the 3CXDesktopApp, a desktop client version of the company’s VoIP software, were found to contain malicious code.

While more time and effort will be needed to fully reconstruct and study this incident, our analysis of the malicious files used in the attack points strongly to a compromise of 3CX’s software build pipeline, resulting in modifications that inserted malicious code to the 3CXDesktopApp software package.

There are many possible explanations for how such a thing could happen. However, our analysts focused on investigating the two most likely scenarios: a compromise of the 3CX development pipeline that resulted in malicious code being added during the build, or the possibility of a malicious dependency being served by a package repository. The former is represented by the SolarWinds incident while the latter theory is closer to the supply chain attacks commonly found in open source repositories like npm and PyPI.

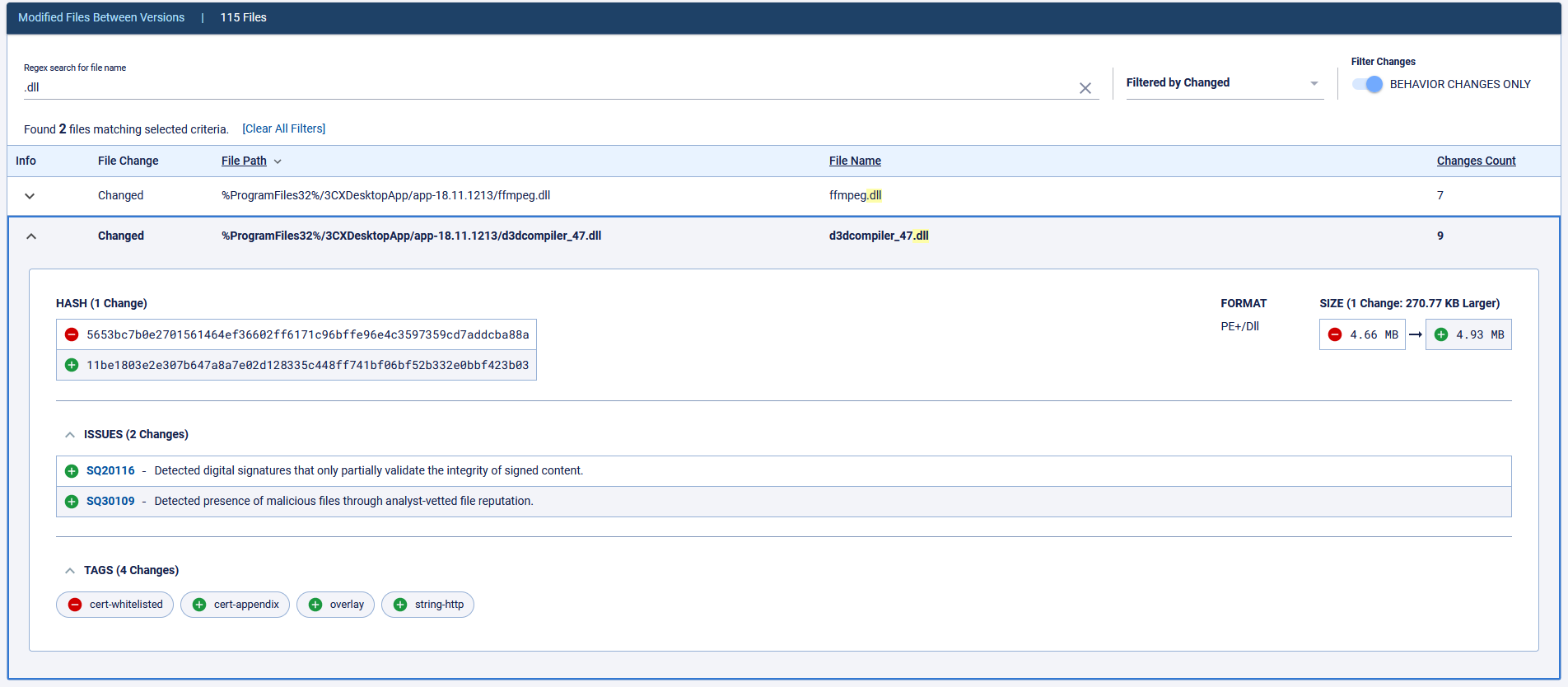

ReversingLabs analysis shows that attackers appended RC4 encrypted shellcode into the signature appendix of d3dcompiler.dll, a standard library used with OpenJS Electron applications such as 3CXDesktopApp. Another standard Electron application module, ffmpeg was modified with code to extract and run the malicious content from the d3dcompiler file.

Evidence of those changes are clearly visible when comparing images of “clean” versions of the 3CXDesktopApp with subsequent, tampered versions. The ReversingLabs Software Supply Chain Security platform identified signatures in the appended code pointing to SigFlip, a tool for modifying the authenticode-signed Portable Executable (PE) files without breaking the existing signature. Subsequently, our threat research platform linked malicious code added to ffmpeg library to code found in SigLoader, another malicious tool used by an advanced persistent threat group in multiple campaigns.

As was the case with the compromise of SolarWinds’ Orion software, the manner in which the malicious code was added to the 3CXDesktopApp is of little value to 3CX customers who downloaded malicious code onto internal systems. However, it should be of intense interest to organizations engaged in software development, as it points to the need for increased scrutiny of compiled software images to detect malicious code, unexplained modifications or other discrepancies that may be a critical, early indicator of a supply chain compromise.

SEE RELATED:

- Analysis: The 3CX attack was targeted — but the plan was broader

- Webinar: Deconstructing the 3CX Software Supply Chain Attack

- Deminar: Analyzing the 3CX Software Package

Introduction

3CX is a VoIP IPBX software development company. The 3CX Phone System is used by more than 600,000 companies worldwide and counts more than 12 million daily users, including firms in the automotive, manufacturing, healthcare, aviation and other industries.

Beginning around March 22, 2023 customers of voice over IP (VoIP) vendor 3CX started peppering the company’s support groups with complaints about an update to the company’s 3CXDesktopApp client running afoul of endpoint detection and response products, which were flagging the update as malicious.

The troubles with the 3CXDesktopApp simmered quietly for days, with customers wondering about “false positives,” until, on Wednesday, reports from a string of endpoint security firms including CrowdStrike and SentinelOne confirmed what many suspected: that the warnings from endpoint protection software were not in error, and that the 3CXDesktopApp had been compromised. By Thursday morning, 3CX’s CEO, Nick Galea, made it official.

“As many of you have noticed the 3CX DesktopApp has a malware (sp) in it,” Galea wrote in a post to a 3CX support page. “It affects the Windows Electron client for customers running update 7. It was reported to us yesterday night and we are working on an update to the DesktopApp which we will release in the coming hours.” Galea advised uninstalling the malicious app and promised more information on the incident.

For customers affected by the incident, the 3CX compromise is serious. CrowdStrike and others have attributed the incident to a threat actor dubbed “LABYRINTH CHOLLIMA,” believed to be associated with the government of North Korea and known for targeting military and political entities. Many of the customers that downloaded the malicious update did not see malicious code activated in their environment. However, Crowdstrike wrote that it has observed malicious activity including hands-on-keyboard actions in a number of 3CXDesktopApp customer environments.

Much will be written about the “what” and the “who” of the attack (what APT group is responsible). We would like to focus on the “how.” That is, how was it that malicious actors placed information stealing code within a signed 3CXDesktopApp software update?

Our analysis of the malicious update points either to a compromise of the 3CX development pipeline that resulted in malicious code being added during the build, or the possibility of a malicious dependency being served by a package repository. The attack on 3CX — though sophisticated — had clear indicators that could have tipped off 3CX to the breach before customer systems were affected.

Detecting the 3CX compromise with differential analysis

The ReversingLabs Software Supply Chain Security (SSCS) platform analyzes software packages prior to release or at any stage during development. As a final step in the build process, the ReversingLabs platform has unique visibility into the state of a produced software artifact. That gives it the ability to detect the multitude of software supply chain attack possibilities. Scanning binaries, without the presumption of having the source available, can surface software supply chain compromises within the developer’s source code, their build environment, or the dependencies used to assemble the final software package.

A required capability for detecting supply chain compromises is the ability to track the evolution of software packages through differential analysis of their contents. This includes the raw metadata properties of each software component in the release, as well as their respective behaviors. Odd or inexplicable changes between builds should be considered a cause to investigate a possible compromise. This becomes even more important when software packages include components that are pre-compiled at offsite locations and, therefore, not subject to review prior to deployment.

A required capability for detecting supply chain compromises is the ability to track the evolution of software packages through differential analysis of their contents.

Changes introduced in 18.12 had red flags

In the case of the 3CXDesktopApp: 3CX distributed macOS DMG and MSI installer packages containing the compromised update. ReversingLabs has also identified a NuGet package containing the version 18.12.416 of the 3CXDesktopApp among the compromised artifacts we analyzed.

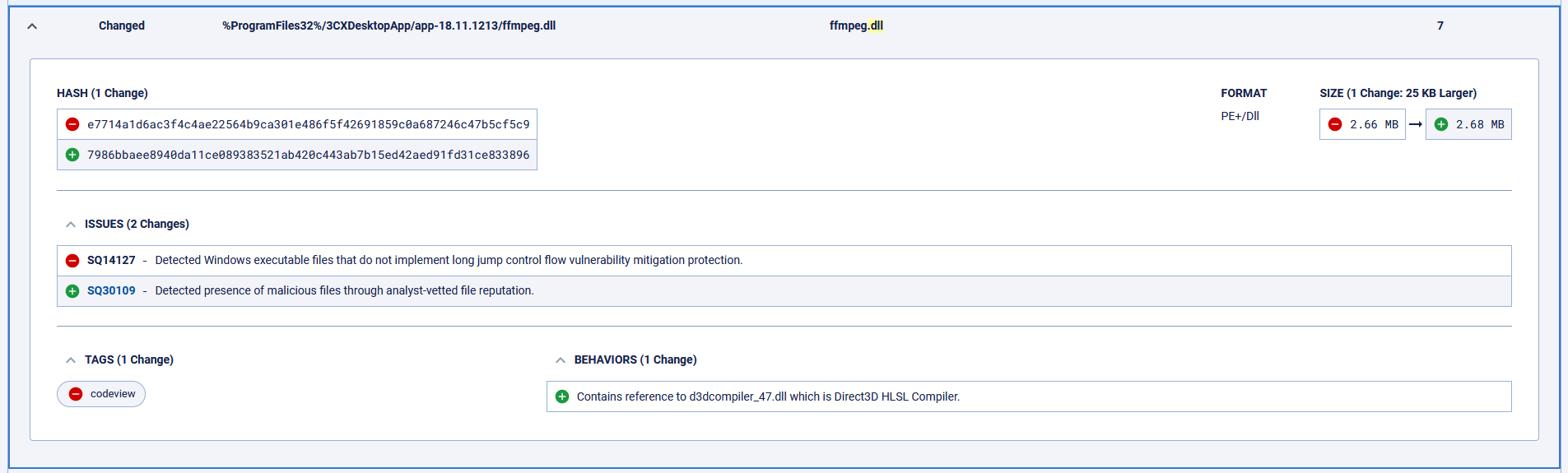

When we look at the MSI packages distributed by 3CX through our solution, and make a diff between v18.11.1213 (the last known good version) and v18.12.407 (the first known compromised version), a number of red flags pop up that are cause for a deeper investigation.

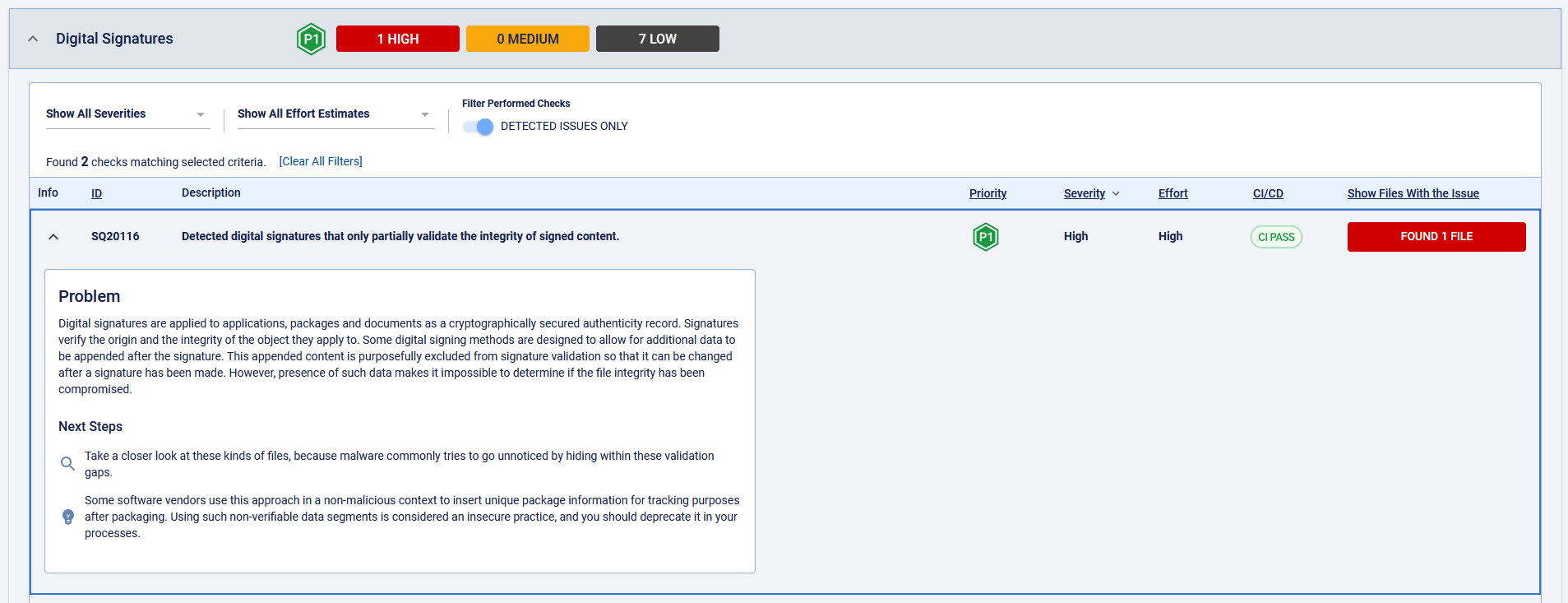

For example: ReversingLabs Software Supply Chain Security policy SQ20116 detects that a Microsoft digitally signed-binary has been modified post-signing without breaking the signature integrity. This is not something that would normally happen during the build process and it is not something that could happen inadvertently. Developers would have had to make a conscious choice to implement a change like this, and that would never happen for a software component they own.

However, doing so is a great technique for ferrying malicious code onto a system under the cover of a digitally signed (and therefore “legitimate”) binary. Freely available, off the shelf tools like SigFlip and SigLoader help facilitate these kinds of operations. For that reason, the ReversingLabs supply chain security solution makes the following recommendation when it encounters a digitally signed binary that has been modified post-signing:

Investigate: Take a closer look at these kinds of files, because malware commonly tries to go unnoticed by hiding within these validation gaps.

This warning popped up in our analysis of 3CXDesktopApp in association with d3dcompiler, a standard library used with OpenJS Electron applications such as 3CXDesktopApp. Adding to the alarm in our analysis of the 3CXDesktopApp was the behavior of another standard Electron file, ffmpeg, which we saw referencing the d3dcompiler, the tampered file.

Other indicators of malicious intent were hard to come by as the malware hides itself as a statically linked function with ffmpeg library. But even without observing the malware execute, there’s enough suspicious goings-on just in the diff between the two 3CXDesktopApp updates to warrant a deeper investigation.

Digging into the suspicious changes

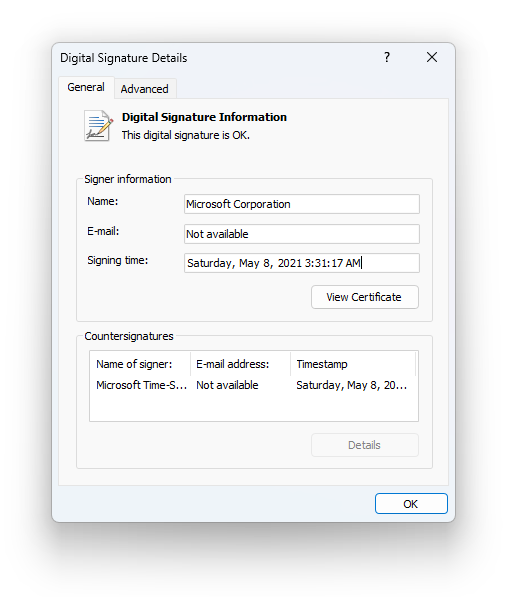

The choice of these two DLLs -- ffmpeg and d3dcompiler_47 - by the threat actors behind this attack was no accident. The target in question, 3CXDesktopApp is built on the Electron open source framework. Both of the libraries in question usually ship with the Electron runtime and, therefore, are unlikely to raise suspicion within customer environments. Additionally, d3dcompiler_47, the tampered-with file, is signed with a certificate issued to Microsoft Corporation and Windows digital signature details report no issues related to the signature. For endpoint protection applications, a signed binary using a legitimate certificate from a reputable firm like Microsoft is likely to get the “green light".

Figure 1: Windows digital signature details for d3dcompiler_47

The “smoking gun,” in this case, was a combination of RC4 encrypted shellcode into the signature appendix of d3dcompiler and a reference to the d3dcompiler library that was added to the ffmpeg library.

There was no sensible explanation for these changes, as there were no functional changes to d3dcompiler_47 to warrant such a change. That pointed in the direction of malicious functionality being added within the ffmpeg library. And, indeed, detailed analysis shows that malicious code was added to that DLL. It is invoked shortly after the call to its entry point to extract the RC4 encrypted malicious content from the signature appendix of d3dcompiler.

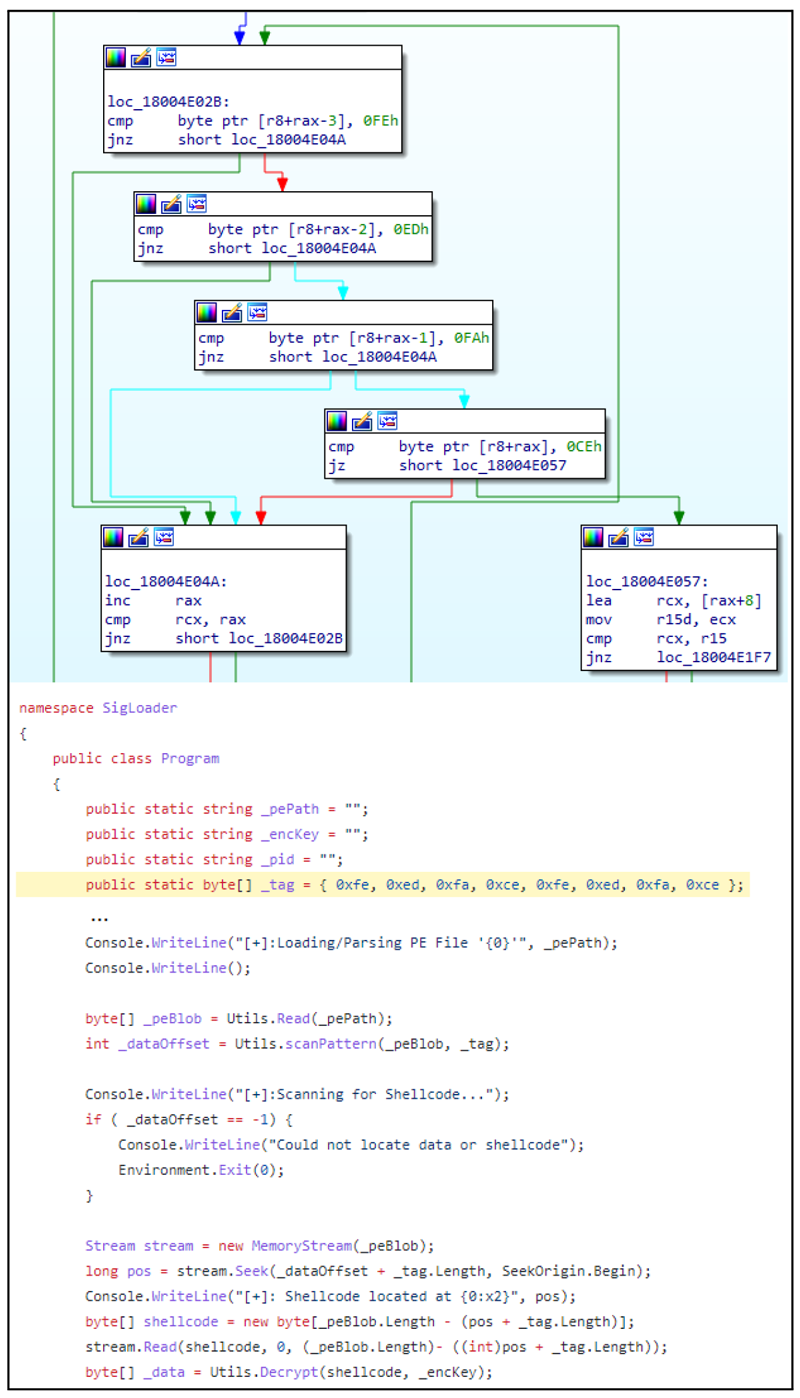

When we looked more closely, we saw that the beginning of the RC4 encrypted content was marked by a signature: 0xFE 0xED 0xFA 0xCE 0xFE 0xED 0xFA 0xCE. That specific sequence of bytes is what we term a “magic signature” — a value that the program seeks and interprets in a specific way. In this case, the sequence is known to be associated with the SigLoader tool.

When SigLoader encounters this signature, it knows that a malicious shellcode payload follows immediately after the sequence, which it will extract and decrypt. And, indeed, rest of the appended data after that initial signature contains the encrypted shellcode which is decrypted using the RC4 key: 3jB(2bsG#@c7

Appending data to a signed executable and using the specific magic byte signature are strong signs that the loader payloads were created using SigFlip — a tool designed “for patching authenticode signed PE files without invalidating or breaking the existing signature.” Finally, the code responsible for loading the encrypted data that was added to the ffmpeg library is identical to code found in the SigLoader tool. This is a known technique used by APT#10 in multiple campaigns or intrusion sets.

In this incident, the decrypted payload is a shellcode containing another embedded DLL file that downloads URLs pointing to C2 infrastructure from a Github repository hosting harmless icon files. The URLs pointing to C2 infrastructure are encrypted with AES, Base64 encoded and appended to the ends of the legitimate icon files.

Figure 2: Showing the similarity of loader code found in ffmpeg (above) and the SigLoader tool (below).

Metadata clues point to 3CX compromise

The exact circumstances and early stages of the 3CX breach aren’t known. However, our examination of the metadata from the compromised packages provides important insights into the incident and suggest that there were clues that 3CX may have picked up on that something was amiss with its latest desktop client update.

Based on data from our threat research platform, we can say with confidence that most Electron applications found in the ReversingLabs Cloud have identical PE compilation timestamps for the files in the application. That is because the compile times are predetermined and set by the build system, resulting in compilation stamps that are identical. There is simply no other way to explain how so many files would be built in the exact same second.

In the case of compromised 3CXDesktopApp Electron applications, however, these compilation timestamps differed. The first timestamp, which is found on the majority of the DLLs within the compromised installer package, is 2022-11-30T15:56:23Z. That correlates with the build version of the Electron used by the 3CX development team - Electron v19.1.9.

The second timestamp we discovered only applied to the ffmpeg file. It was 2022-11-12T04:12:14Z and is associated with the build version of the Electron used by malware authors. Furthermore, two of the malicious ffmpeg variants were digitally signed with a legitimate certificate issued to the 3CX company.

What can we conclude from this? Based on this information we estimate that the supply chain incident was caused by the compromise of the repository from which the Electron application binaries were fetched during the build process. As part of the attack, legitimate versions of ffmpeg and d3dcompiler libraries in the compromised repository were likely replaced with malicious versions compiled by the attackers after modifying publicly available ffmpeg source code.

[ReversingLabs researchers] estimate that the supply chain incident was caused by the compromise of the repository from which the Electron application binaries were fetched during the build process.

Unlike legitimate ffmpeg files, the Program Database (PDB) data is stripped from the malicious files in order to remove any data that could reveal the real build time or link them to attackers' development environment.

Once that substitution happened, the rest of the attack was easy sailing. 3CX’s build process was likely designed to automatically sign the latest available components — third-party or otherwise — and include them into the software release package. That means the malicious ffmpeg library, once fetched from the (compromised) repository, was signed without the need for the attackers to steal the digital signing certificates.

There is no data to indicate whether the compromised repository was deployed locally in 3CX or if it was hosted elsewhere. Based on public statements from the company, we can infer that the malicious ffmpeg and d3dcompiler were hosted somewhere on GitHub. ReversingLabs has, so far, been unable to confirm this with the telemetry data we currently have available to us. From what we have seen, there is no evidence that a malicious repository is, or was, hosted on GitHub. And there is no evidence that other developers may be at risk from using the same malicious code like 3CX did.

Conclusion

As the saying goes, “It is not ‘if’ you will be hacked, but ‘when.’” That’s true even for sophisticated operations like software supply chain attacks. Recent history has shown us that malicious actors are growing more and more interested in the access provided by development pipelines, open source and third party code and more. Development organizations can’t keep from being targeted. However, there are ways that they can reduce the impact of any malicious campaign against them. Doing that requires them to be attuned to the techniques and methods that malicious actors use.

In the case of the compromise of the VOIP provider 3CX, there is a lot that is still unknown about how the attack was carried out, or who its intended targets were. However, ReversingLabs analysis of the modifications made to the company’s 3CXDesktopApp suggest that there were telltale signs of tampering with the company’s desktop client software prior to its release. Had these signs been noticed during development, it should have triggered a closer analysis of the software release and, possibly, discovery of the breach and malicious code additions.

As we have shown, evidence of changes to the 3CXDesktopApp are clearly visible in a comparison of “clean” and tampered versions of the client software — changes that point to the use of SigFlip and SigLoader, known suspicious/malicious off the shelf tools that are in the tool belt of advanced persistent threat (APT) actors.

As with the compromise of SolarWinds Orion codebase, this incident underscores the need for development organizations to look beyond the risks posed by software vulnerabilities and insecure code.Threats such as malicious open source modules, tampering with software dependencies and attacks on internally developed modules and builds are growing. When successful, these attacks not only threaten the security and reputation of the affected software firm, but those of all its customers as well. Detecting such threats during development and before software ships is key to preventing the next 3CX-style incident.

Indicators of Compromise (IOC) list

| filename | sha1 |

| 3cxdesktopapp-18.12.407.msi | bea77d1e59cf18dce22ad9a2fad52948fd7a9efa |

| 3cxdesktopapp-18.12.416.msi | bfecb8ce89a312d2ef4afc64a63847ae11c6f69e |

| 3CXDesktopApp-18.12.416-full.nupkg | f7f1b34c2770d83e2250e19c8425a4bec56617fd |

| 3CXDesktopApp_v18.12.407.0.exe | 6285ffb5f98d35cd98e78d48b63a05af6e4e4dea |

| 3CXDesktopApp_v18.12.416.0.exe | 8433a94aedb6380ac8d4610af643fb0e5220c5cb |

| ffmpeg.dll | bf939c9c261d27ee7bb92325cc588624fca75429 |

| ffmpeg.dll | 188754814b37927badc988b45b7c7f7d6b4c8dd3 |

| ffmpeg.dll | ff3dd457c0d00d00d396fdf6ebe7c254fed2a91e |

| d3dcompiler_47_v10.0.20348.1.dll | 20d554a80d759c50d6537dd7097fed84dd258b3e |

| decrypted shellcode | 8b81f6012fd748f0fed53eeef72164435ad618ac |

| samcli.dll (embedded in shellcode) | 3b88cda62cdd918b62ef5aa8c5a73a46f176d18b |

| 3CXDesktopApp-18.11.1213.dmg | 19f4036f5cd91c5fc411afc4359e32f90caddaac |

| 3CXDesktopApp-18.12.416.dmg | 3dc840d32ce86cebf657b17cef62814646ba8e98 |

| libffmpeg.dylib (universal) | b2a89eebb5be61939f5458a024c929b169b4dc85 |

| libffmpeg.dylib (universal) | 769383fc65d1386dd141c960c9970114547da0c2 |

| libffmpeg.dylib (x86-64) | 354251ca9476549c391fbd5b87e81a21a95949f4 |

| libffmpeg.dylib (x86-64) | 5b0582632975d230c8f73c768b9ef39669fefa60 |

Keep learning

- Go big-picture on the software risk landscape with RL's 2025 Software Supply Chain Security Report. Plus: See our Webinar for discussion about the findings.

- Get up to speed on securing AI/ML with our white paper: AI Is the Supply Chain. Plus: See RL's research on nullifAI and replay our Webinar to learn how RL discovered the novel threat.

- Learn how commercial software risk is under-addressed: Download the white paper — and see our related Webinar for more insights.

Explore RL's Spectra suite: Spectra Assure for software supply chain security, Spectra Detect for scalable file analysis, Spectra Analyze for malware analysis and threat hunting, and Spectra Intelligence for reputation data and intelligence.