Introduction

Large malware campaigns with the potential to cause severe damage and operational problems on a nationwide scale often attract the attention of government institutions like the FBI, DHS and similar organizations. To help prevent further malicious activity and reduce the malware’s damage potential, these institutions produce technical reports that describe the malware in detail.

While those threat reports can have varying levels of detail and technical complexity, they almost always have a list of IOCs (Indicators of Compromise) with information about file samples and infrastructure used in malicious campaigns. Those IOCs are then used by defenders to detect malicious activity in their networks. Even though using the IOC lists is a good way to strengthen the company network security, it is hard to tell how comprehensive they are and how many sample and infrastructure variants they cover.

If a malicious campaign is highly targeted, the malware samples will most likely be adapted and configured to use different infrastructure for different targets. In those cases, there is a big chance that the company network will get infected by a malware sample that isn’t detectable based on the IOC list provided in the related report. Even if such modifications slightly change the program logic, there are a few ways to detect similar malware samples based on metadata extracted during static analysis.

This blog will demonstrate how our Titanium Platform can be used for that purpose on a real-world scenario of the Hidden Cobra APT group. You will learn how to find similar malware samples targeting your organization that aren’t covered by released IOC lists.

Hidden Cobra

Hidden Cobra (often referred to as Lazarus) is an APT group linked to North Korea. Most researchers estimate it has been active for the last 10 years. During that time, this group has conducted several malicious campaigns and used different toolsets in most of them. Their malicious activity was continuously investigated by the US government institutions. As a result of those investigations, several malware analysis reports were released, containing IOC lists that can be used to detect malicious activity. On May 12th, 2020, three new reports were released describing the COPPERHEDGE, TAINTEDSCRIBE and PEBBLEDASH threats. We selected them for demonstration purposes, since they describe ongoing campaigns.

Copperhedge

The first malware tool we will analyze is Copperhedge. As described in the threat report, this tool is a full-featured RAT that comes in six variants. Each variant is accompanied by a list of IOCs, which we will use as a starting point. We will try to find more samples that are not mentioned in the report, extract their configurations, and add them to the IOC list. Technical descriptions of all variants are provided in the report, so there’s no need to go into more detail here.

There are three things to look for during sample analysis:

- Import decryption and loading at execution startup

- Commands supported by the RAT

- C2 domains

Variant A

The two samples mentioned in the report will be used as the starting point for our threat search. Samples from this variant load RC4-encrypted imports at the beginning of the execution. Supported commands start at the 0x123459 index. The three domains stored in plaintext are used for C2 communication.

Titanium Platform can group processed files based on the RHA1 file similarity algorithm. During file processing, Titanium Platform also performs metadata extraction. Extracted metadata fields can be used to find related samples that aren’t similar enough to be put into the same RHA1 group, but still have something in common.

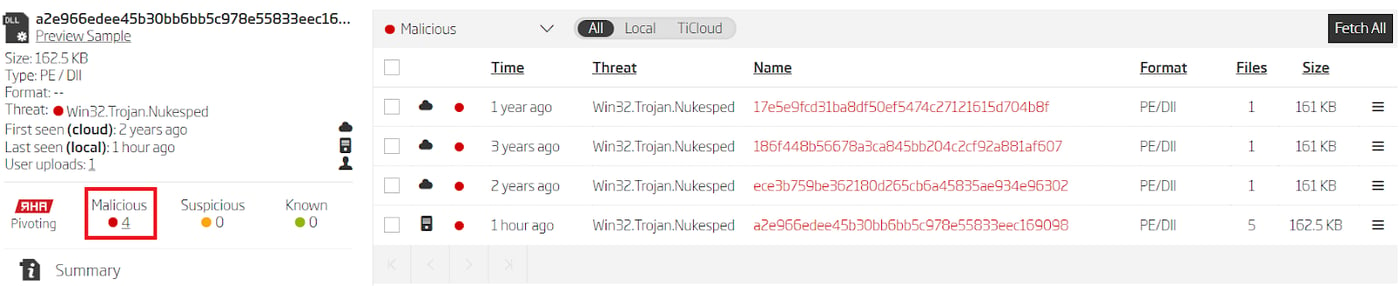

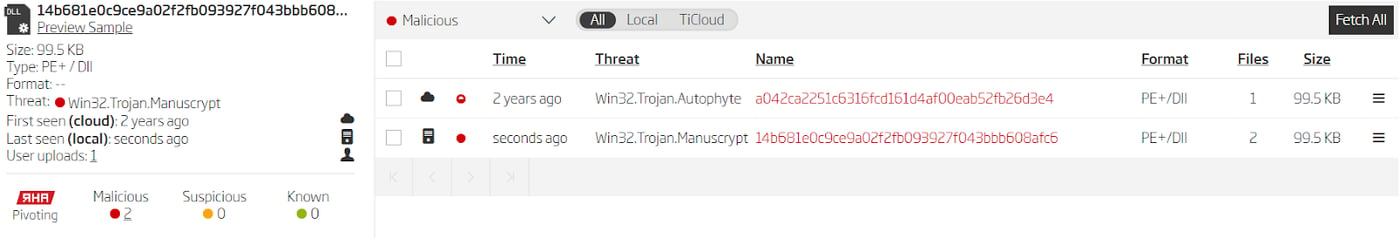

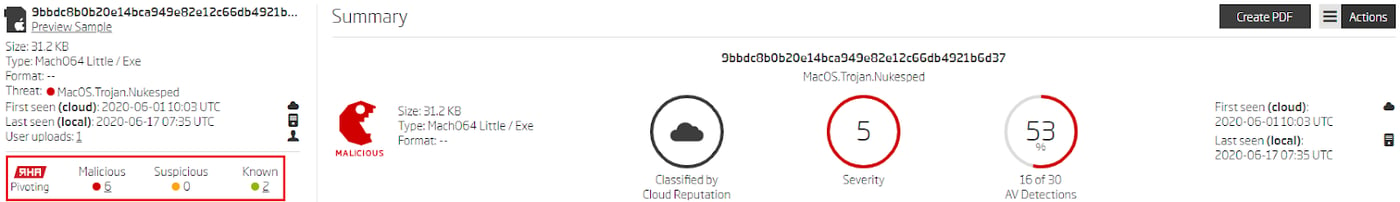

Processing these two samples with Titanium Platform and looking at their RHA1 buckets reveals 3 new samples that weren’t mentioned in the report.

Similar files grouped by RHA1 algorithm

The metadata extracted from these new samples uncovers that they use different C2 domains also not mentioned in the initial report.

Example of a C2 domain list contained in one of the found samples

Besides RHA1 pivoting, different metadata fields can be used for discovering similar files. For PE files, you can use the following fields:

- Imphash

- Compile timestamp

- Section hashes

- Resource hashes

- ...

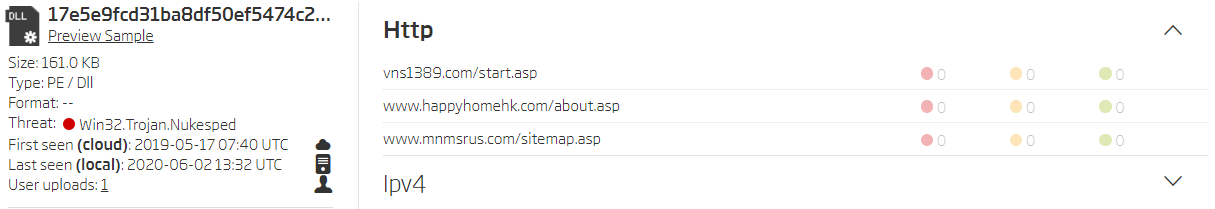

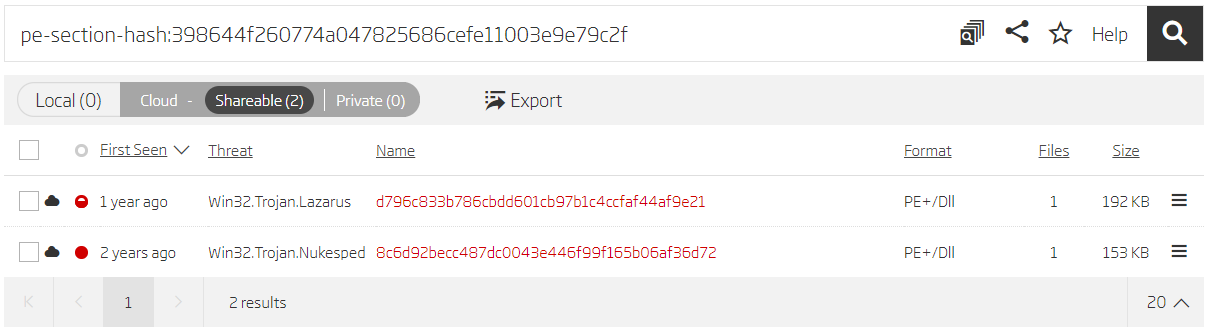

These techniques are used on previously discovered samples to hopefully find more potential threats. Pivoting on the .rsrc section hash of the 17e5e9fcd31ba8df50ef5474c27121615d704b8f sample gives two more files and uncovers more C2 domains.

Search based on section hash

Whenever a new sample is found, the whole search process is repeated. Think of it as a ball of tangled ropes where you need to pull the leads until you completely untangle it.

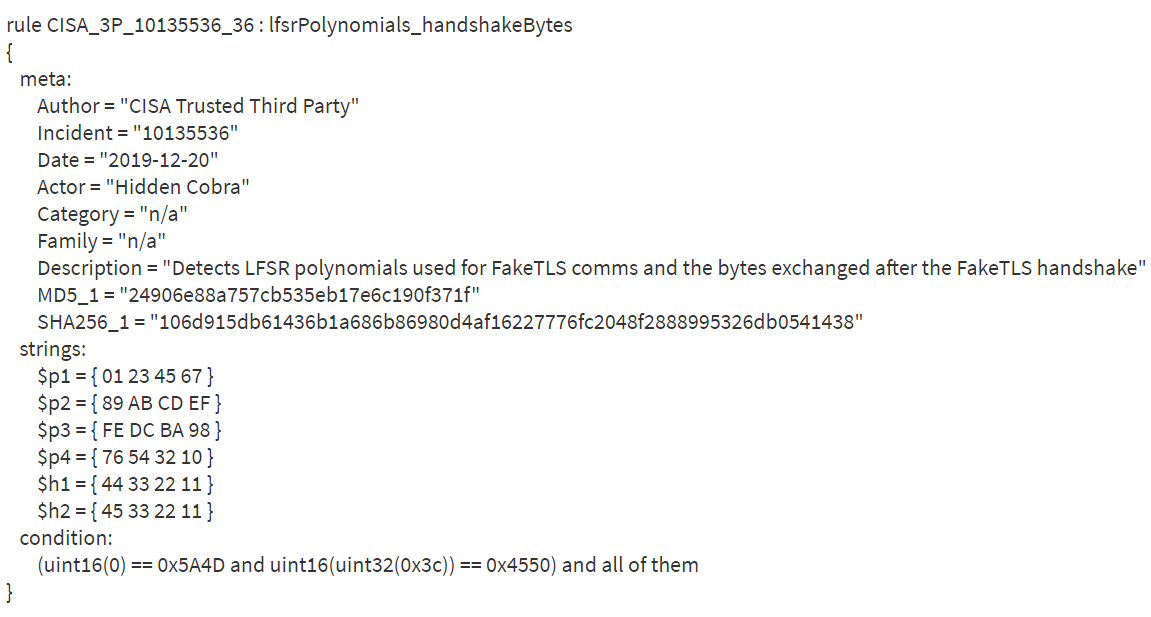

If you don’t have any samples to start with, you can use YARA retro hunt as a starting point. Threat warnings often provide some YARA rules as a way to detect samples. Sometimes, those rules will be very specific, and will provide precise hunting results. Other times they will be too generic, and will get triggered on unrelated samples. The biggest problem with YARA rules provided for Hidden Cobra tools is that a lot of those tools reuse the same codebase, and it is often hard to clearly distinguish between different variants used in the past.

In our example, running a YARA retro hunt with the provided rules results in new samples, and disassembler analysis relates them to Hidden Cobra activities. Some of them were already seen in previous threat reports about a variant named BANKSHOT.

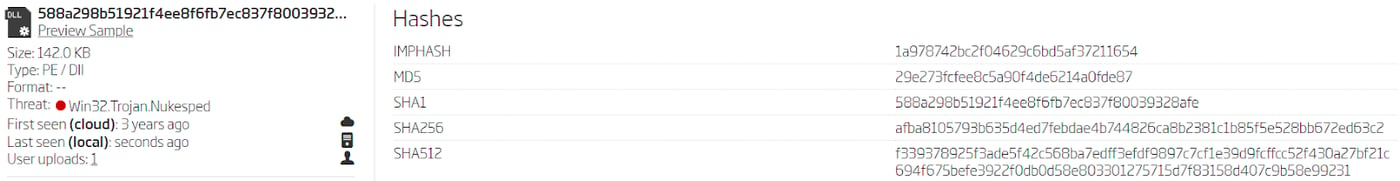

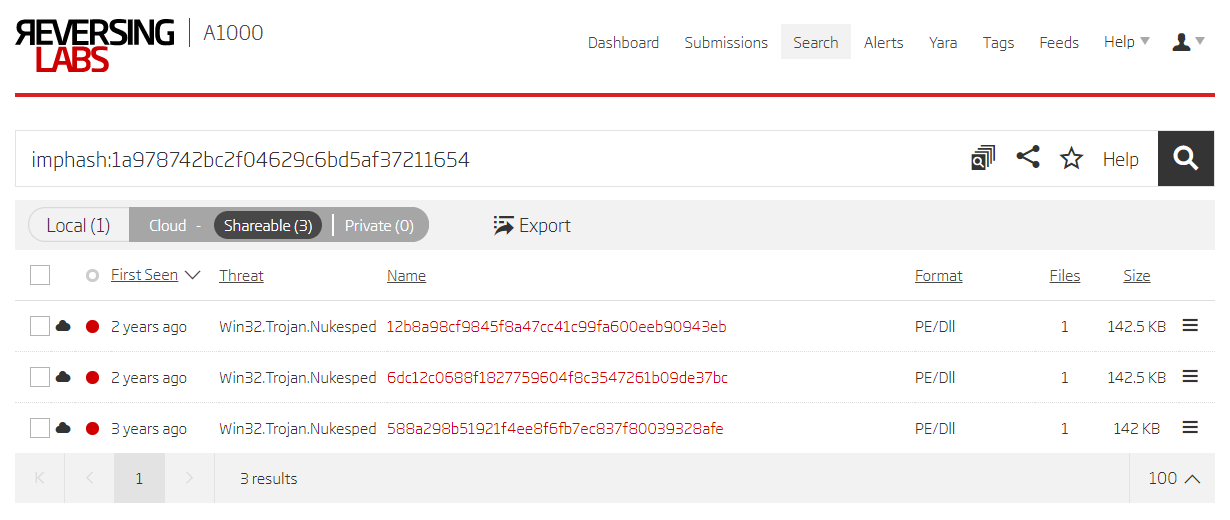

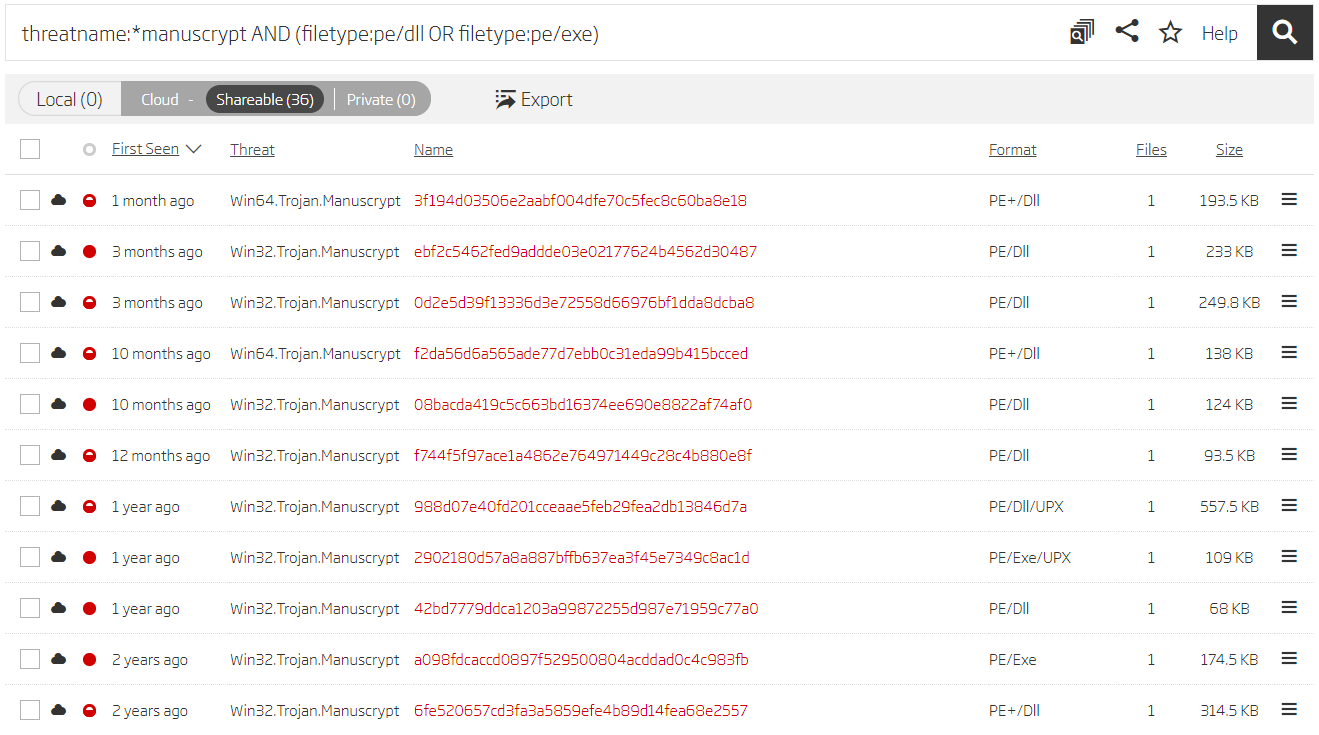

The next step is to analyze the results and filter the ones similar enough to be marked as variant A. Filtered results are then used as a starting point for the pivoting process already demonstrated on the initial samples. For example, the provided YARA rule matched the 588a298b51921f4ee8f6fb7ec837f80039328afe sample. Searching the imphash extracted from that sample gives 2 new samples, and analyzing them reveals more previously unknown C2 domains. The process is then repeated again until there are no more leads to follow.

Search based on imphash

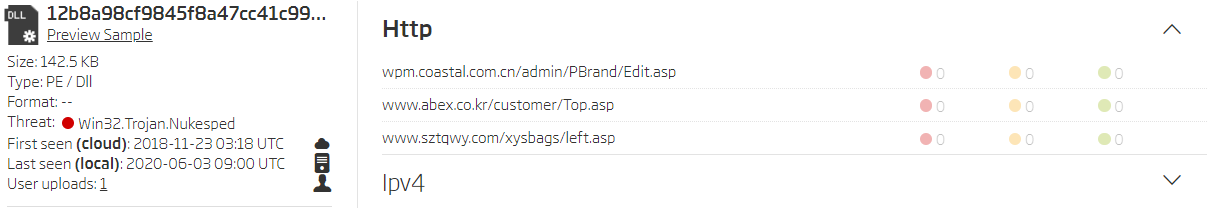

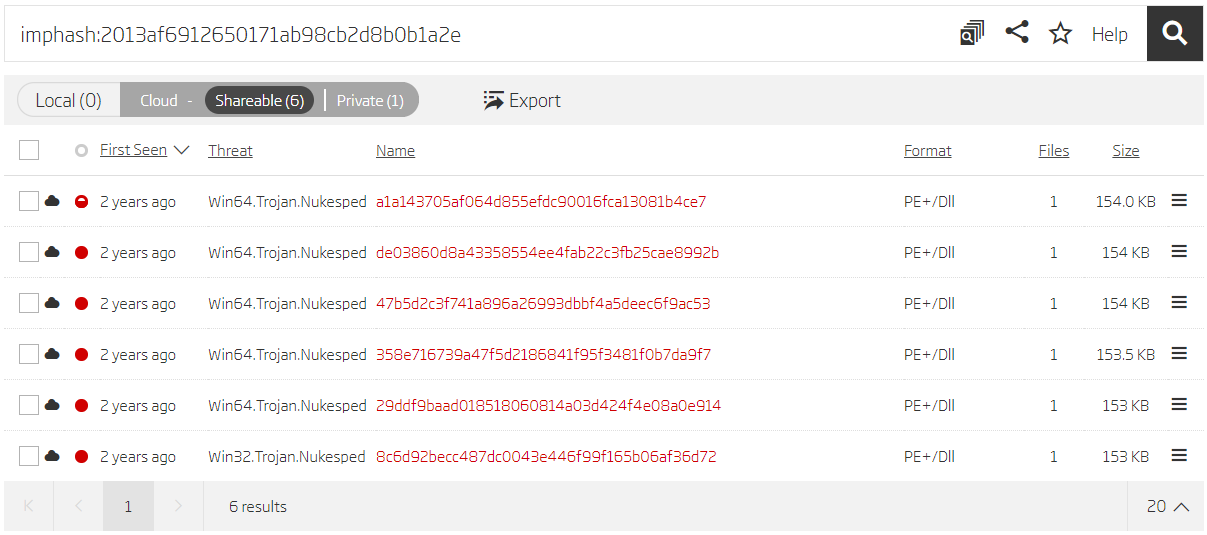

In case you don’t have any input samples and the provided YARA rules didn't match any results, another good option is to try the Titanium Platform’s search feature. Use the threatname keyword to find your initial sample set. The great thing is you don't need to know the exact name, as wildcard characters can be used for partial threat name matching. The threat report refers to this Hidden Cobra tool as Copperhedge, but it also mentions another name - Manuscrypt. Based on this information, we can search for all samples with threat names ending in manuscrypt.

Search based on manuscrypt threat name

Using wildcard characters enables matching both 32-bit and 64-bit samples in an easy way. Logical clauses can be used to make the search more targeted, and to eliminate potential false positives. In this case, the search is refined to PE/DLL and PE/EXE files in order to eliminate a bunch of archive files from which they were extracted. The construction of logical clauses is a powerful feature that enables fine maneuvering between different search results, and allows you to find relevant samples faster.

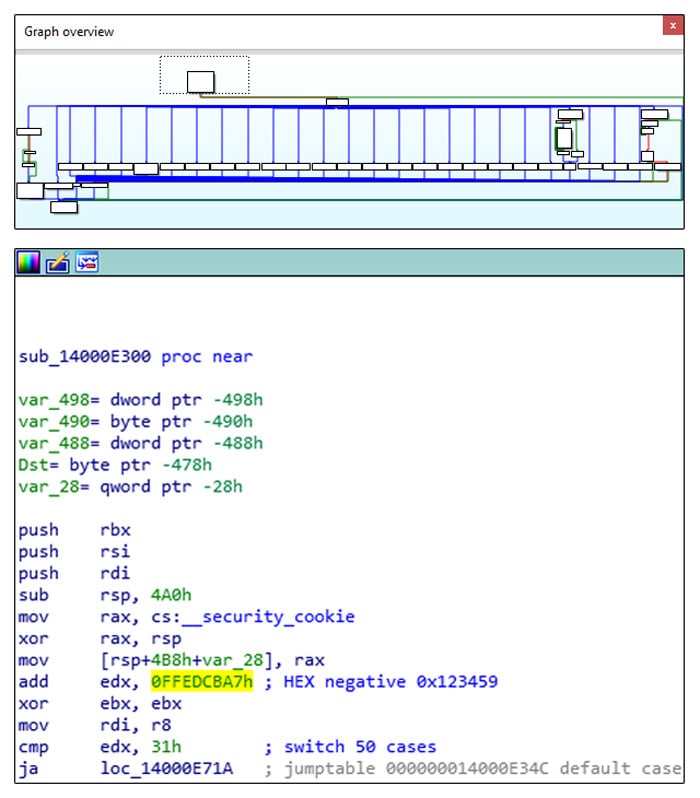

Analyzing the search results gives a few more samples that use domains not found in the reports. One interesting sample is 14b681e0c9ce9a02f2fb093927f043bbb608afc6. It uses the same 0x78292E4C5DA3B5D067F081B736E5D593 RC4 key for import decryption and has the same hardcoded string *dJU!*JE&!M@UNQ@. Interestingly, these domains were already used in a previous Hidden Cobra operation named Ghost Puppet described in another malware threat report. Samples from this variant also look very similar to the ones described in the threat report related to the operation Star Cruiser. This strengthens our previous conclusion that Hidden Cobra tools reuse code and infrastructure. Just like before, analyzing other samples in the same RHA1 bucket gives us more domains and a new threat name to use as a starting point for a new round of searching.

Finding new threat names

Searches based on the manuscrypt threat name also returned a few files that use different RC4 keys for import decryption.

One such example is the 03138278b603bc120b2cba001a8adb0b2d7d82ea sample. It has the same command-dispatching routine, and the commands start at the previously mentioned 0x123459 index.

Top level view of command dispatching routine

It also has typical import-loading code in its WinMain function, but the RC4 key used in this case is 0x38D90F98DD0A903CB156499FE3691588.

Import loading routine

This information can be used to create YARA rules that will serve as a starting point for a new round of searching. Pivoting around different metadata fields accompanied by YARA retro hunting and threat name searching can result in a high number of discovered samples in just a few iterations of the described search process. Search results for variant A are summarized in the appended file at the end of the IOC list section. Notice how just the two initial samples and a single YARA rule helped in finding all those new IOCs.

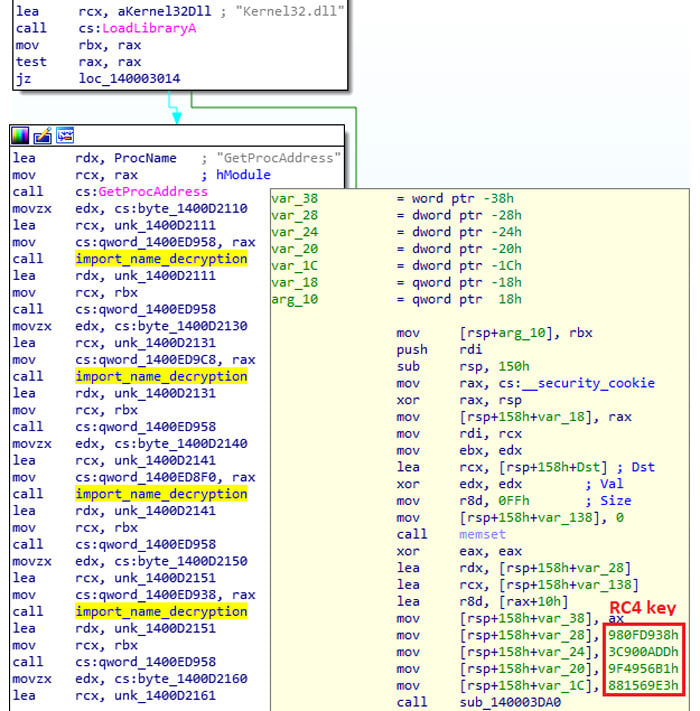

Variant B

The threat report for this variant provides 11 samples and no YARA rules. Analyzing the samples with Titanium Platform reveals some new ones. For example, searching by imphash from sample 29ddf9baad018518060814a03d424f4e08a0e914 returns 4 more files.

Search based on imphash

Pivoting on the .reloc section’s SHA1 hash gives another result. When using section hashes for pivoting, it is advisable to avoid all-zero sections, or sections with generic content (for example, a .rsrc section of a file that has only generic resources like a manifest or some common dialogs). Generic sections are found in many samples, and they generate unwanted results during the search process.

Search based on section hash

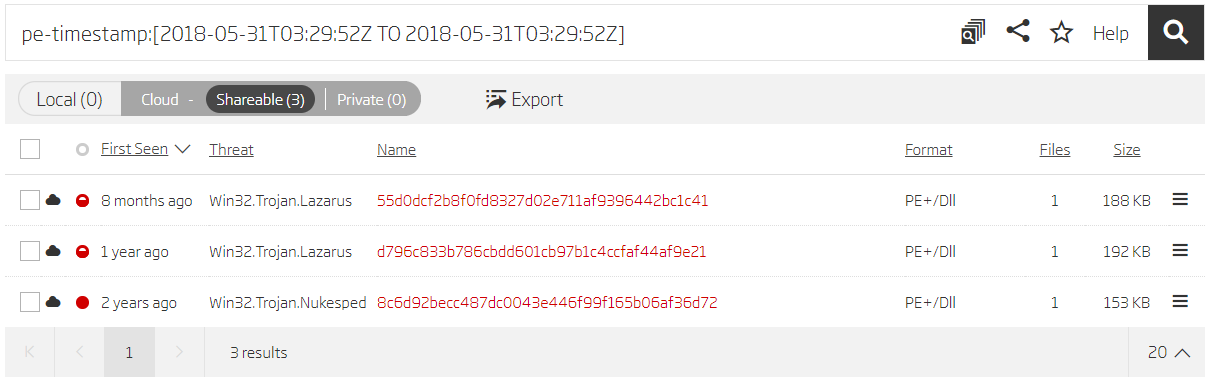

The search process is the same as for the variant A. Find new samples, pivot on their metadata, and repeat on any new results. This time we can use the compilation timestamp from the sample 8c6d92becc487dc0043e446f99f165b06af36d72 found in the first iteration to reveal more samples.

Search based on timestamp

When using timestamps as the search criteria, keep in mind that they can also be generic and lead you the wrong way. The best example of this is 0x2A425E19 (1992.06.19 22:22:17), a timestamp that appears in a wide range of Delphi executables.

Variant C

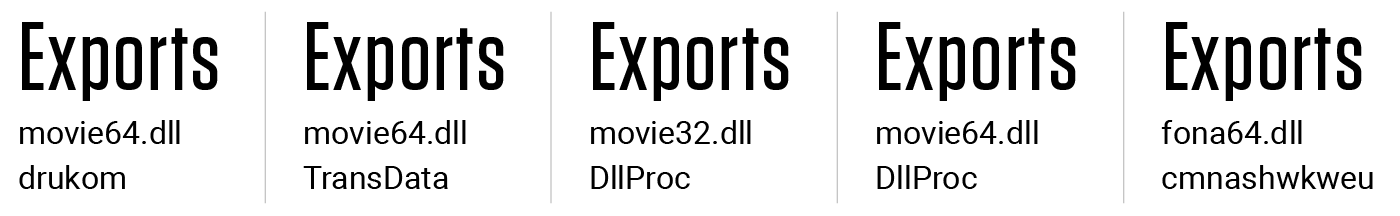

This variant is an excellent example of why you should always try pivoting using as many metadata fields as possible. The best pivoting results are usually achieved by looking into files grouped by RHA1, and by imphash value. However, in this case, processing all four input samples produced only one new result. Luckily, there are many metadata fields that can be used for pivoting. All input files are DLLs, and looking at their exported functions reveals interesting library names.

Exported functions and original file names

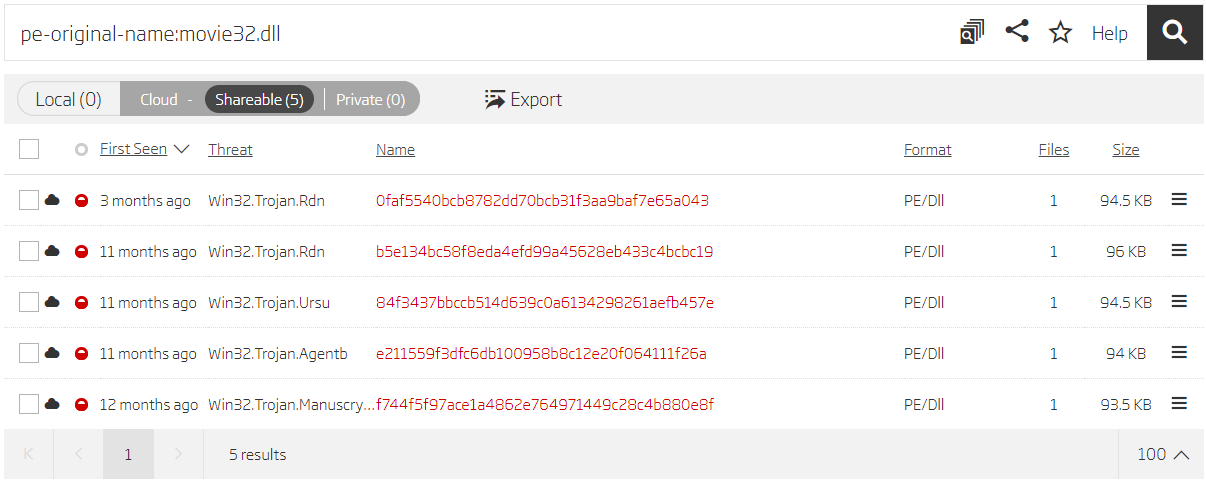

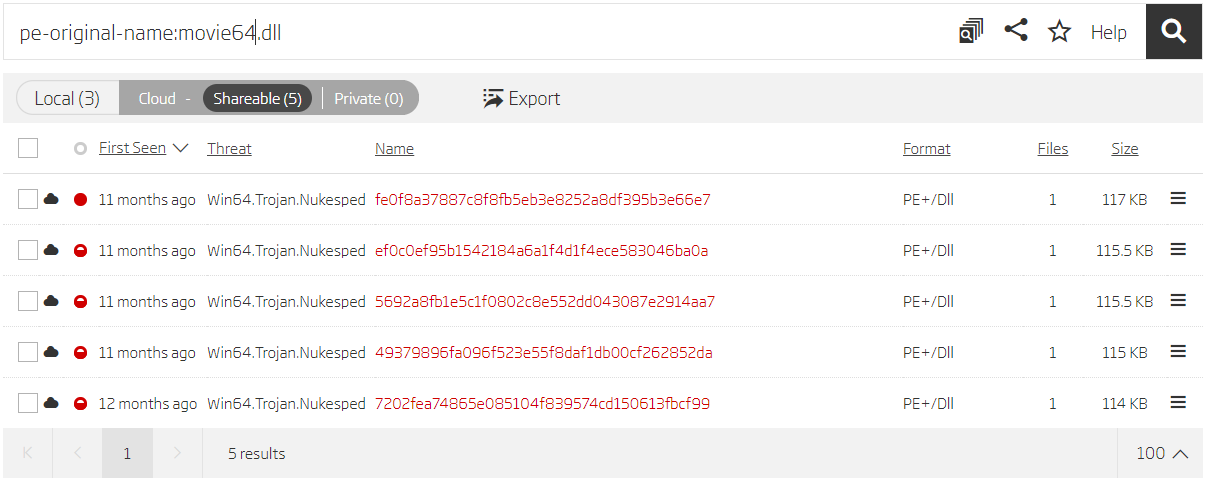

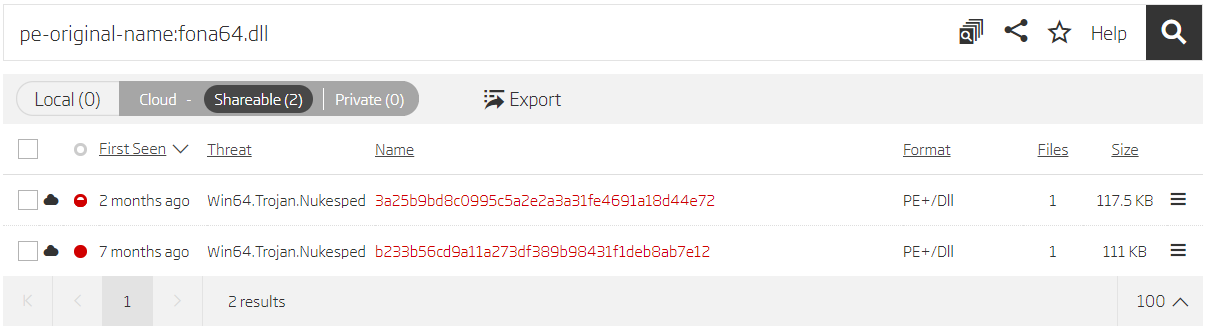

Taking a closer look, we see there are two samples exporting the DllProc function, and it seems that the same malware is compiled in both 32-bit and 64-bit variants. Other samples have similar library names, but have different exported functions, and come only in 64-bit variants. If there’s a 32-bit variant of a file exporting the DllProc function, why doesn’t it exist for other samples? The easiest way to confirm this assumption is by performing a search for the library name used as the original file name.

Search based on original file name

A short analysis summary of the newly discovered samples is displayed in the following table. Comparing compilation timestamps with the time when the samples were first seen in ReversingLabs TitaniumCloud can reveal how malicious actors operated. It is interesting to notice that sometimes only a few hours passed from the moment the sample was compiled to the moment when it was used. Samples in each pair use the same domains for C2 communication, and every pair comes with a new set of domains.

| SHA1 | Compile timestamp | First seen timestamp | Original file name | Exported Func |

| f744f5f97ace1a4862e764971449c28c4b880e8f | 2019-06-18T12:03:21 | 6/20/2019 14:26 | movie32.dll | DllProc |

| 7202fea74865e085104f839574cd150613fbcf99 | 2019-06-18T12:03:26 | 6/20/2019 12:01 | movie64.dll | DllProc |

| e211559f3dfc6db100958b8c12e20f064111f26a | 2019-07-12T00:48:01 | 7/12/2019 19:52 | movie32.dll | DllEntryPointer |

| 49379896fa096f523e55f8daf1db00cf262852da | 2019-07-12T00:48:08 | 7/12/2019 20:00 | movie64.dll | DllEntryPointer |

| 84f3437bbccb514d639c0a6134298261aefb457e | 2019-07-15T13:19:53 | 7/22/2019 16:46 | movie32.dll | TransData |

| ef0c0ef95b1542184a6a1f4d1f4ece583046ba0a | 2019-07-15T13:20:00 | 7/22/2019 16:46 | movie64.dll | TransData |

| 0faf5540bcb8782dd70bcb31f3aa9baf7e65a043 | 2019-07-19T00:32:01 | 3/13/2020 20:34 | movie32.dll | drukom |

| 5692a8fb1e5c1f0802c8e552dd043087e2914aa7 | 2019-07-19T00:31:55 | 7/19/2019 3:47 | movie64.dll | drukom |

| b5e134bc58f8eda4efd99a45628eb433c4bcbc19 | 2019-07-23T06:17:14 | 7/23/2019 14:08 | movie32.dll | drukom |

| fe0f8a37887c8f8fb5eb3e8252a8df395b3e66e7 | 2019-07-23T06:17:02 | 7/23/2019 14:08 | movie64.dll | drukom |

| 3a25b9bd8c0995c5a2e2a3a31fe4691a18d44e72 | 2019-08-21T00:49:49 | 3/25/2020 17:00 | fona64.dll | cnamnhs |

| b233b56cd9a11a273df389b98431f1deb8ab7e12 | 2019-10-22T02:21:16 | 10/24/2019 8:53 | fona64.dll | cmnashwkweu |

Variant C search summary

Variant D, E

The search process was repeated for these variants too, but no new samples were discovered that could be positively related to them.

Variant F

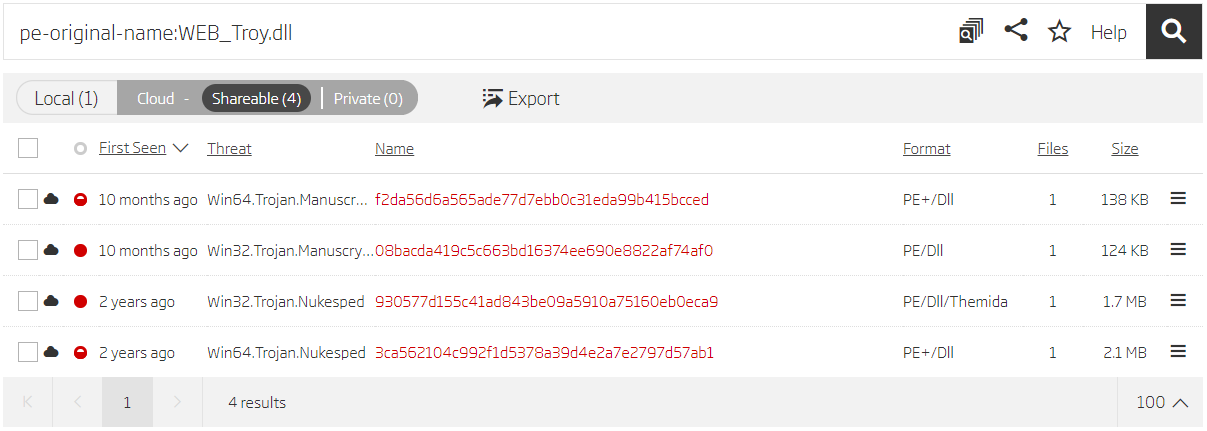

Analyzing variant F samples showed they all have the original file name WEB_Troj.dll. Searching for this parameter exposed another sample.

Search based on original file name

The Description section of the threat report mentions “multi-part HTTP POST messages” used for the communication with the C2 server. Those messages contain specific fields and User-Agent strings that can be used to define a YARA rule for finding more samples.

rule Copperhedge_F {

strings:

$user_agent1 = "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome"

$user_agent2 = "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome"

$form_data1 = "_webident_f"

$form_data2 = "_webident_s"

condition:

($user_agent1 or $user_agent2) and $form_data1 and $form_data2

}

YARA rule for Copperhedge F variant

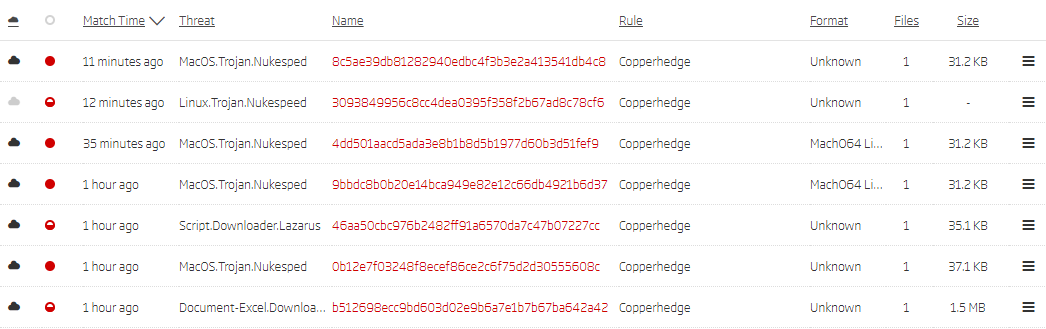

Titanium Platform’s Retro Hunt results show that Hidden Cobra tools aren’t targeting only Windows systems, but also Linux and macOS platforms.

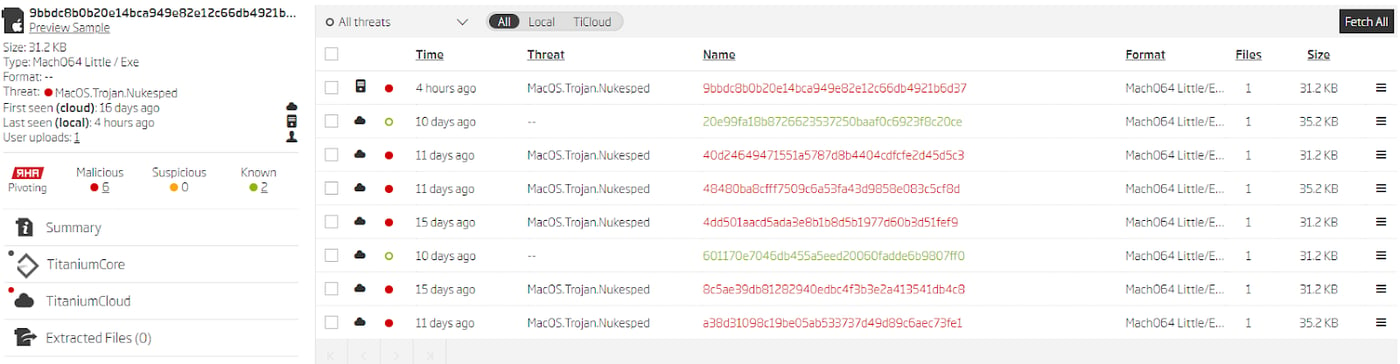

Retro Hunt results

Looking at the list of samples grouped by the RHA1 similarity algorithm uncovers a few samples that didn’t match the provided YARA rule. Disassembler analysis of these files confirms they are also variant F samples, but they use different User-Agent strings and modified POST message fields (_media_1/_media_2 instead of _webident_f/_webident_s). None of the samples from this RHA1 bucket have been seen in ReversingLabs TitaniumCloud before early June 2020, and most of them have a very low percentage of AV detections.

Similar files grouped by RHA1 algorithm

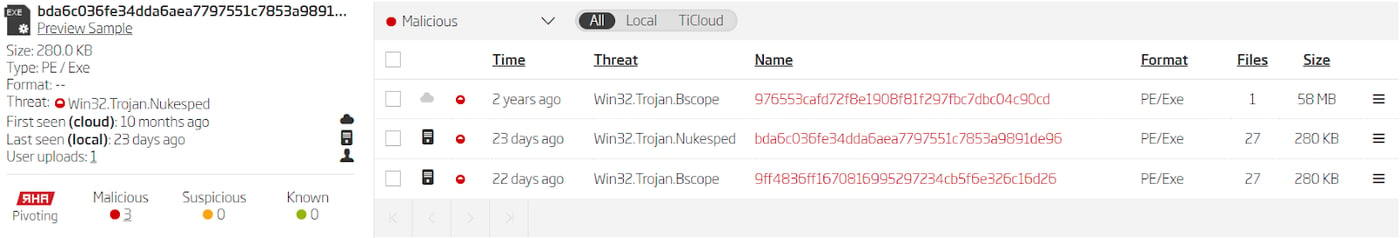

Taintedscribe

The second malware tool we are going to analyze is Taintedscribe. It is described as a full-featured beaconing implant that downloads additional command execution modules after establishing a successful landing point. The report provides hashes of one beaconing implant and two command execution modules that will be used to discover more samples. The report also provides one YARA rule, but it is a very loose rule that would generate many false-positives, so we won't use it for the search.

Example of a loose YARA rule

Titanium Platform shows that the downloader module has two similar files, according to the RHA1 similarity algorithm. These samples use two new IP addresses - 221.161.45.202 and 61.106.174.191. Sample 976553cafd72f8e1908f81f297fbc7dbc04c90cd is identical to the 9ff4836ff1670816995297234cb5f6e326c16d26, but it has some additional data in the overlay.

Search based on original file name

Unfortunately, pivoting on previously described metadata fields didn’t return any new samples for neither the downloader module nor the command execution module. This looks like a dead end, but is it really? The threat report mentions a list of domains extracted from the downloader that are used for TLS communication.

List of the domains used for TLS communication

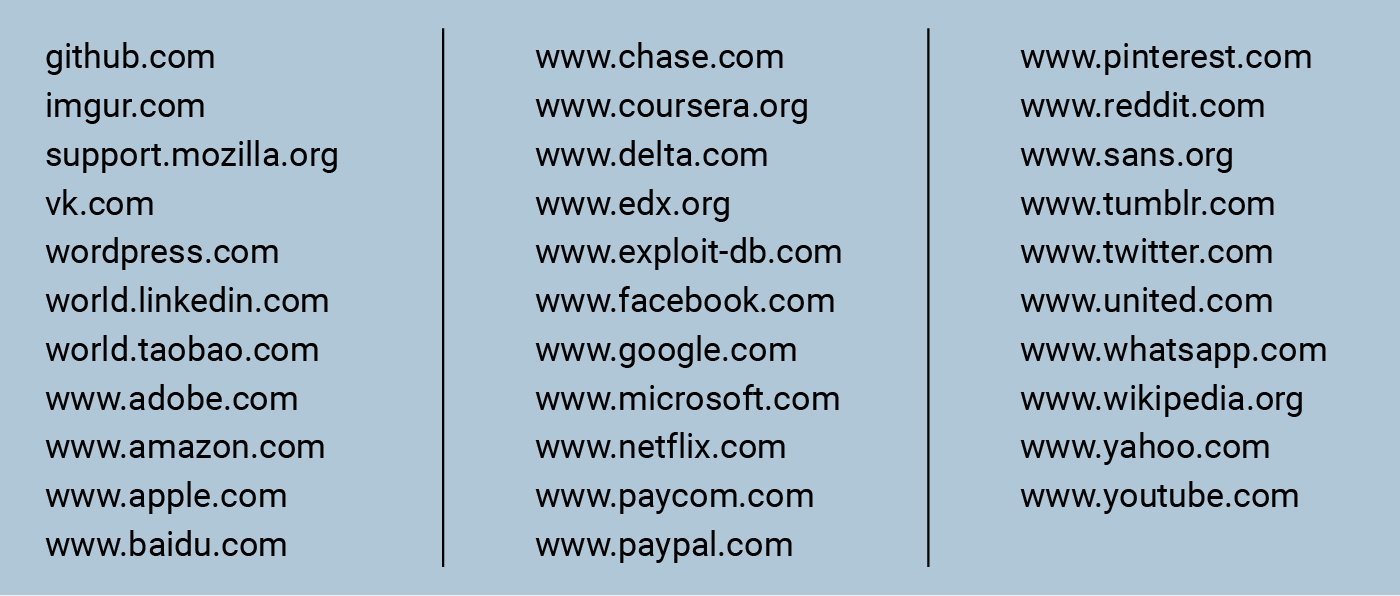

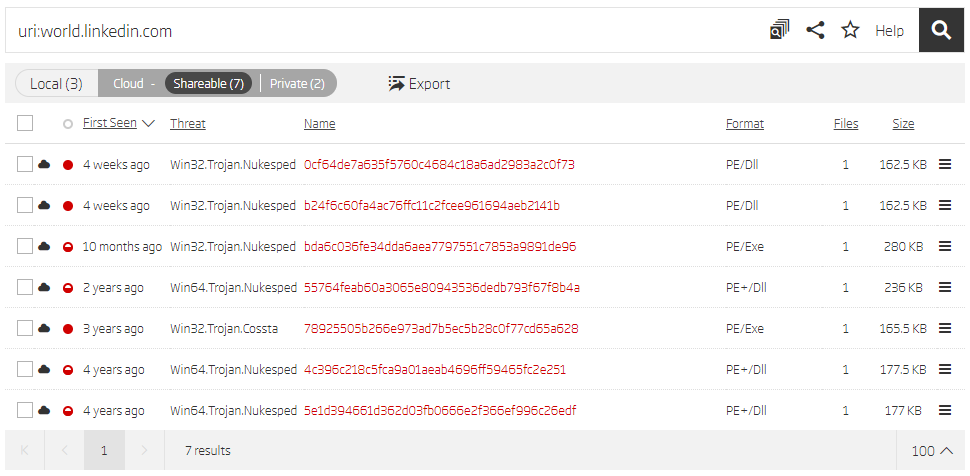

This same list can be found in the samples grouped by the RHA1 algorithm. There are a few somewhat uncommon URIs in the list, like world.linkedin.com or vk.com. Search results based on uncommon URIs uncover even more samples and their C2 IP addresses.

Search based on the extracted URI

A detailed examination shows that these new 64-bit DLL samples are command execution modules. They execute the same commands described in the report, and the segment of program code responsible for command dispatching is almost identical to the one in the input samples. The sample 78925505b266e973ad7b5ec5b28c0f77cd65a628 is a PE/EXE file very similar to the main module. The main difference is that the C2 IPs in this sample are encrypted using a simple encryption. It also uses the same “FakeTLS” scheme and the same byte sequences (0x11223344 and 0x11223345) described in the report.

Repeating the RHA1 pivoting technique on the samples found using URI search gives a few more related samples. This completes the Taintedscribe tool analysis.

Pebbledash

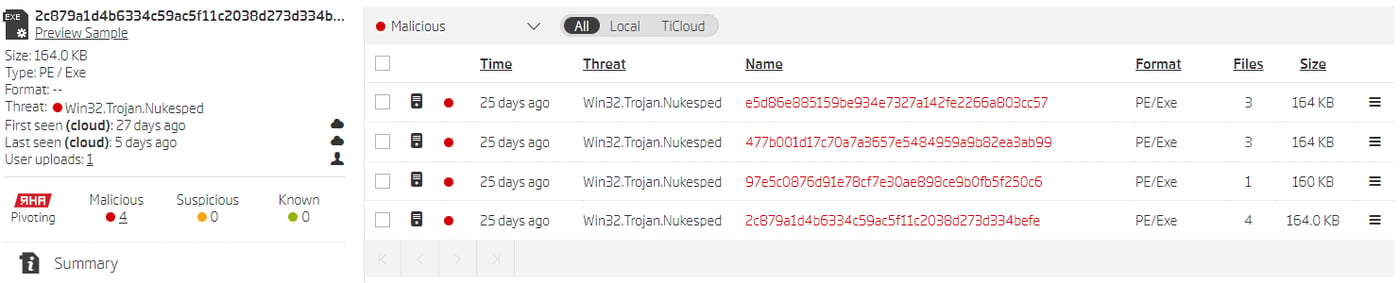

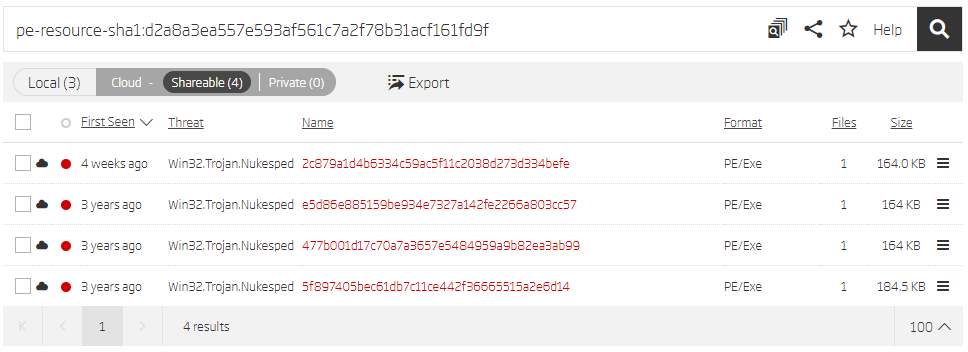

Pebbledash is the third malware tool we are going to analyze. It is also described as a full-featured beaconing implant, but doesn’t use additional command execution modules like Taintedscribe. Only one sample hash is provided in the supplied threat report. As always, the first thing to check is RHA1 file similarity grouping. It gave us three more samples.

Similar files grouped by RHA1 algorithm

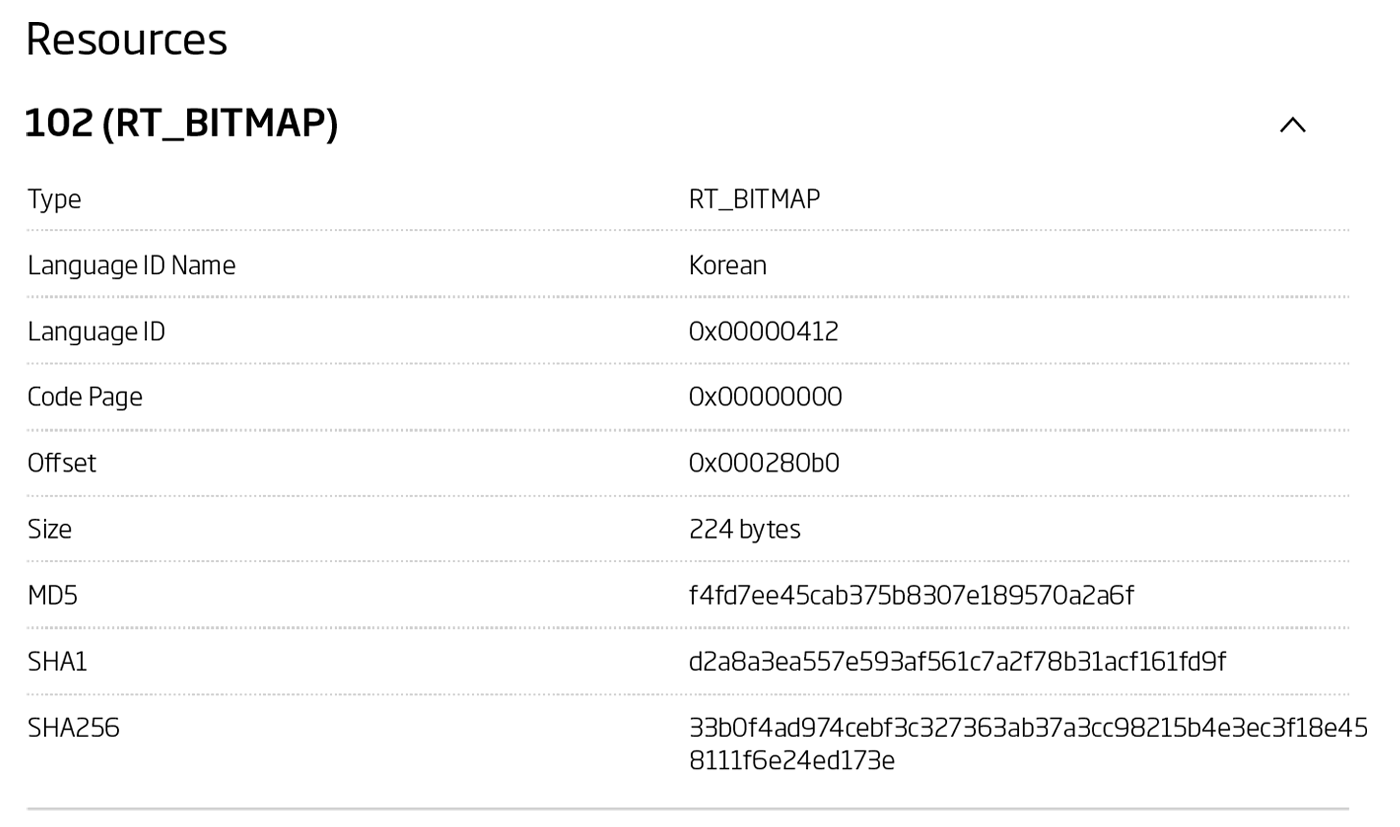

Unfortunately, the usual pivoting fields didn't return any new results. However, looking at the resources embedded in the 2c879a1d4b6334c59ac5f11c2038d273d334befe sample, one item stands out: a bitmap resource with the language field set to Korean.

Bitmap resource from the 2c879a1d4b6334c59ac5f11c2038d273d334befe sample

Resources can sometimes be excellent targets for pivoting purposes. Samples can come with unusual bitmaps and icons that don’t even have a logical visual representation, but are instead used as a data container. Malware samples occasionally contain specific binary resources required for some of their functionalities to work properly. For example, this could be some kind of a decryption key, or a certificate used for authenticating on a C2 server.

The Titanium Platform Advanced Search feature supports searching based on resource hashes. Search results for the bitmap resource hash contain the three already mentioned samples, but also an additional one not found in the previous search queries.

Search based on resource hash

Further pivoting on found samples didn’t result in anything new. YARA retro hunt with the YARA rule provided in the report did not return any new samples either, apart from the ones already found.

Conclusion

Publicly released threat reports are a great source of information that organizations can use to improve their threat detection, primarily through IOC lists. Those lists often provide only a small number of samples that the researchers had at their disposal, and should be enriched by more detailed threat hunting research.

In this case we were able to find 90 additional file samples, 38 domains, and 9 IP addresses. The research also uncovered samples that target Mac and Linux platforms, which wasn’t mentioned in the original reports.

The appearance of the discovered samples in ReversingLabs TitaniumCloud, compared to the samples mentioned in the related threat reports, ranges from a month earlier to even four years earlier in some cases.

Most of the found samples were first seen in ReversingLabs TitaniumCloud in the period between 2018 - 2020, but there are also some samples that date all the way back to June 2016. Finding related samples can be used to discover security incidents that happened a long time ago but were not detected at that moment. A few of the found samples date back to 2014 and it is very likely that they were used in some of the previous operations like Bankshot, but they were mentioned in the blog to explain how Titanium Platform can assist you at discovering potentially undetected relations between different campaigns observed in the past.

This blog post demonstrated how Titanium Platform can help you take advantage of one such threat report on the actively used Hidden Cobra tools. Titanium Platform makes it easy to discover additional threat samples, even without reverse engineering expertise. Repeating simple search queries based on just a few metadata fields can provide valuable results. The researcher doesn’t even need to understand the details of the underlying file format - it is enough to know which metadata fields can be useful.

IOC list

The following links contain the data extracted from the newly discovered samples related to the analyzed tools. They are grouped as described in the original threat report. Keep in mind that all the samples are related to the HiddenCobra activities, and that some of them are quite difficult to distinguish from one another. Information related to files from the referenced reports was not duplicated.

Copperhedge - A:

https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/Copperhedge_A_IOC.txt

Copperhedge - B:

https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/Copperhedge_B_IOC.txt

Cooperhedge - C:

https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/Copperhedge_C_IOC.txt

Cooperhedge - F:

https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/Copperhedge_F_IOC.txt

Pebbledash:

https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/Pebbledash_IOC.txt

Taintedscribe:

https://blog.reversinglabs.com/hubfs/Blog/Taintedscribe_IOC.txt

- Download our Titanium Platform Solution Brief

- Download our A1000 Advanced Hunting Options Datasheet

Keep learning

- Go big-picture on the software risk landscape with RL's 2025 Software Supply Chain Security Report. Plus: See our Webinar for discussion about the findings.

- Get up to speed on securing AI/ML with our white paper: AI Is the Supply Chain. Plus: See RL's research on nullifAI and replay our Webinar to learn how RL discovered the novel threat.

- Learn how commercial software risk is under-addressed: Download the white paper — and see our related Webinar for more insights.

Explore RL's Spectra suite: Spectra Assure for software supply chain security, Spectra Detect for scalable file analysis, Spectra Analyze for malware analysis and threat hunting, and Spectra Intelligence for reputation data and intelligence.